Just over twelve months ago I was in my last year of the art academy when we moved into the new building. This transition came with some resistance, seeing as the existing one was fantastic. It was the kind of place where students could muck around with paint, brushes, and all sort of crazy things on sticks for four years without interference. A place that encouraged you to dive into your studio and explode in a flurry of all the materials that you could find and afford. A place with countless colourful corners where every so often you’d find someone napping, or maybe even living secretly for months, where you’d have to take a great deal of effort to find a bare spot without paint splatters or some artistic statement. It was a building we all were extremely proud of.

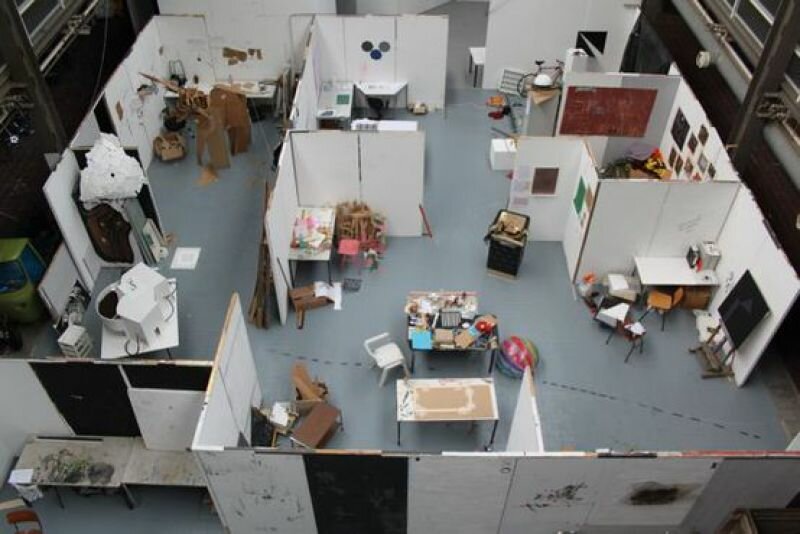

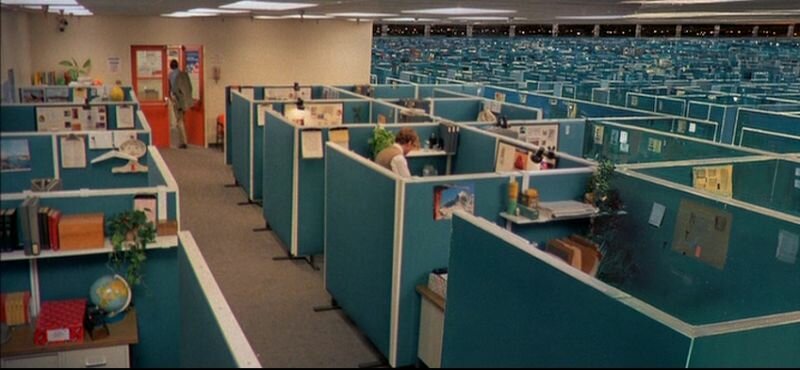

Now, you might not expect this from an art student, but it turns out that of all the sorts of students, they’re the last that should be taken out of their natural habitat. The students shuffled hesitatingly through the halls of the new building. Disapprovingly, they glared at the clean classrooms, the new canteen, searching for a point of recognition that could only be found in their familiar brightly painted lockers—the only furniture to make it from the old building, and the only splash of colour within their sterile new habitat. The quiet mumbling soon evolved into loud commentary: the lamps were hung too low, the electric sockets were at precisely the wrong height, the walls were gray and every nail and speck of paint had to be deliberated, and goddamnit! the place was just like an office! How on earth could an academy student develop inside the confines of the office space?

It’s a great question that I’ve had plenty of time to think about this last year. As it turns out, it’s been nearly a year since I’ve graduated, of which I’ve spent five months working at an office. Despite this cruel and ironic twist of fate, I figured I’d take the opportunity to test the theory that I’d devised during that move. I’m convinced that you should be able throw an academy student anywhere and that they should be able to come up with fantastic works.

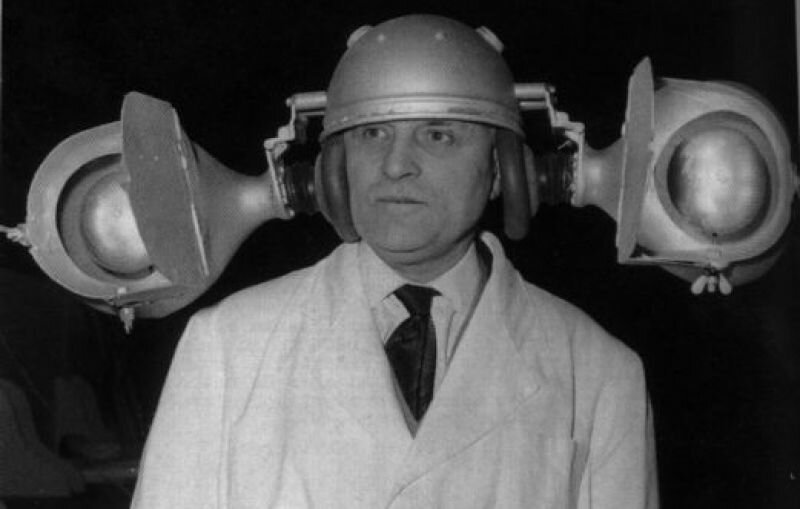

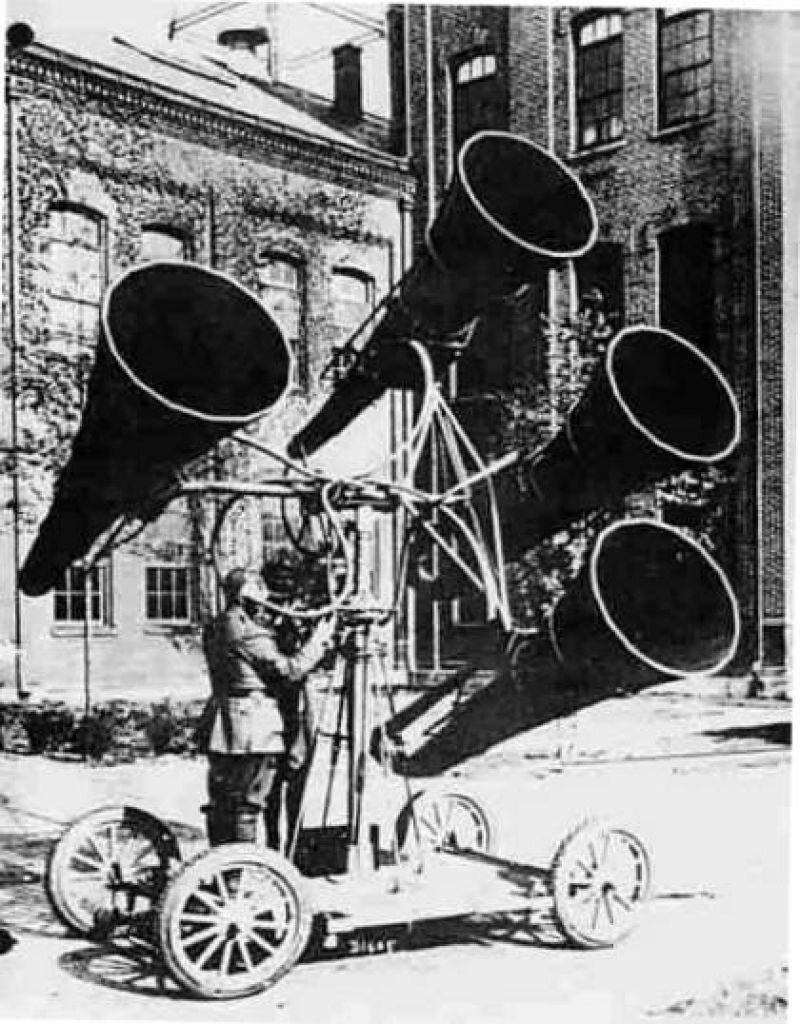

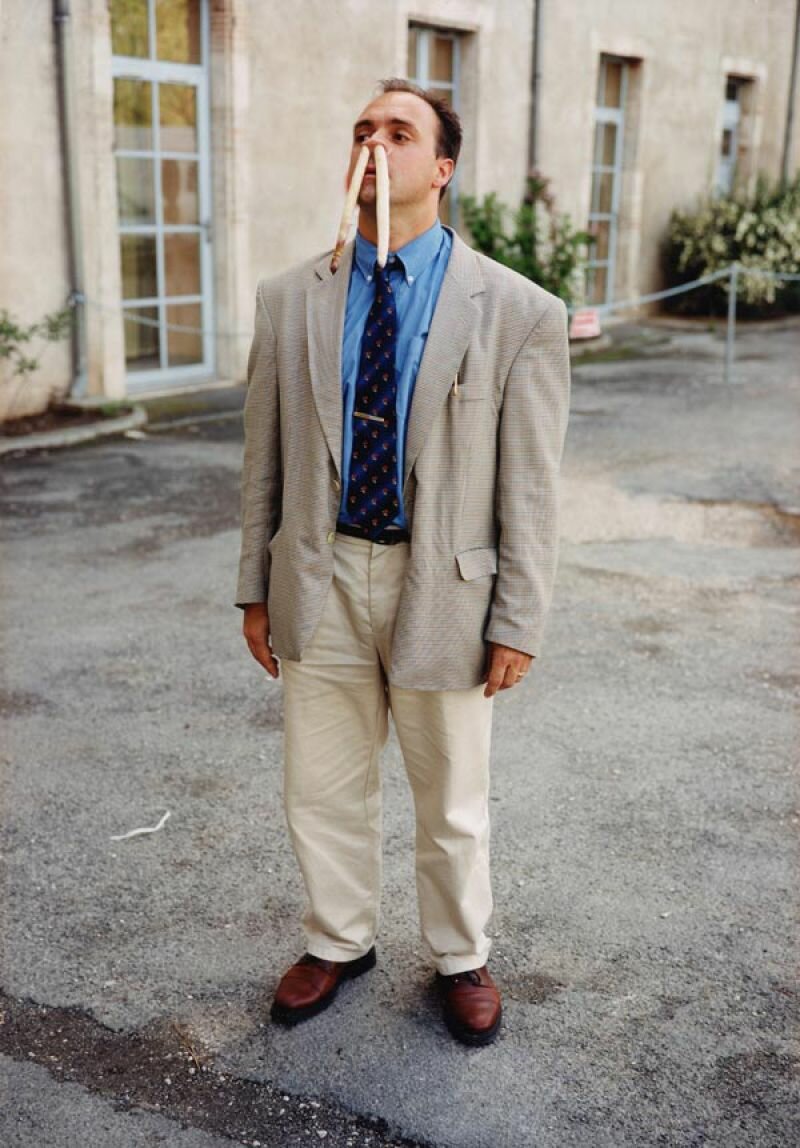

In fact, I believe that the academy goer can sometimes flourish best in places where you might not expect it. His skills and slightly odd views could offer him those pearls of perspectives to transform that place into a more beautiful and more entertaining place. Those who have been there for years often have lost the ability to come to these new perspectives. It’s comparable to seeing an ordinary word for the first time, repeating the word tenfold and feeling amazed at the queerness of that word. It seems to me that the academy student often approaches the ordinary in this fashion, which gives him a sort of super power, like an artistic night vision goggle constantly strapped around his head, allowing him to solve problems quicker, expose structures, and come up with interesting observations that others don’t seem to notice. Like an artistic spy on the work floor.

Of course, this is not a test that I had wilfully subjected myself to. I’d be lying if I said that I hadn’t wished for a flying start, exhibiting my work all over the world. I must admit, I was early to suspect that I might not be in for such a golden start. Luckily, I had been trained for this moment by years of birthday gatherings where uncles, aunts, neighbours and acquaintances would pose that all telling question: “So what can you do with your degree once you’ve graduated?” I always said I’d just find a job somewhere and continue making and creating because I simply could not do otherwise. And so it went. I had worked very hard at devising a safety net for myself in a wonderfully ethical shop that was forced out of business and my safety net was relentlessly torn to bits. It was pretty shit, but there’s not much to do about it. Once I’d crawled back up, I began to apply to the jobs for which my Bachelor of Fine Art held absolutely no relevance (in other words: every job.)

As if that wasn’t confronting enough, it got worse. Dancing around the black hole, I was accosted from all angles by people with expectations of me that couldn’t be further from the truth. For example, during my first job interview I was told that being an art student I should have made an artwork of my CV. Because my CV was so neat and normal, I could have at least tried a little harder as a certified artist. Distracted, I suggested I send a CV in collage form, or as super experimental film via WeTransfer, after which everyone would herald me and hire me directly. Or that I would work for nights on end on an enormous and lavish sculpture that would testify my skills and characteristics that I could roll into the job agency. “Screw your artistic CV! No one would ever buy that,” I thought. That being said, this experience did, however, inspire me to make a book full of ideas for an artistic curriculum vitae.

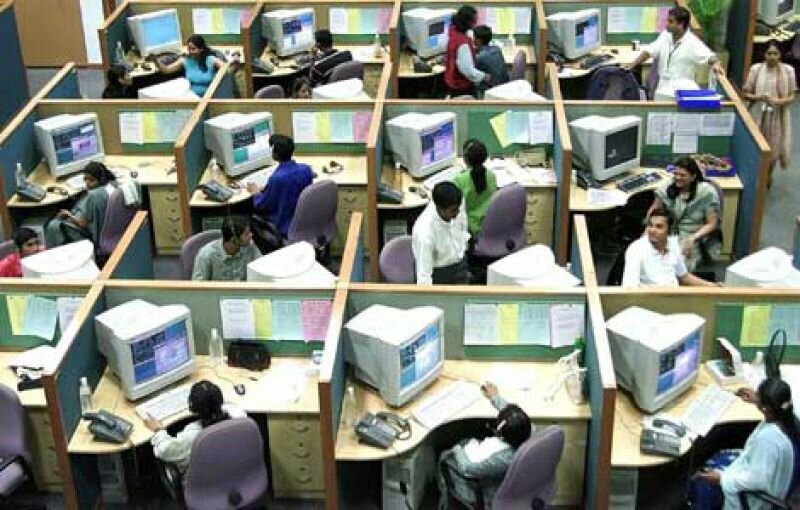

Meanwhile, despite my lack of creativity, the job agency hired me to work at an office and gave me a very smart title that only confused my CV even further. My life at the office was set to begin. I worked in a hugely enormous tower with sixteen floors that I could only enter with entry card 2198. This is something that I know because I tried and failed. Each day I’d greet every man and woman in suit (apart from casual Friday, of course,) chatted at the coffee machine, and made many copies. Life at the office was frighteningly simple: pulled a few thousand staples of out dossiers, opened the envelopes, entered and printed out long lists of data, stacked them on top of each other, bundled them with rubber bands, laid them in the cupboard, only to start on the next stack. I did this from 8 am to 4.30 pm, all the while listening to a radio that was hardly audible. Friends and family soon began their many probing questions. Was I holding up alright, was it not killing my soul, was I not ripped from my safe habitat, how was I dealing with it?

But I actually quite enjoyed my time at the office. From the first time I cycled to work, I had begun observing. I observed those who took the same route to the office. This meant that I crossed paths with the same cyclists, for a while the sun came up at the exact moment that I cycled over the bridge, a giant flock of birds would fly from the roof of the stadium, from the top of a dyke I could look into a sweet little house where (if I was on time) I could see a gentleman eating his breakfast (if I was running late, he’d be gone.) Entering the office,, I’d step over the vacuum cleaner’s orange cable and greet the cleaning lady. Once in my workspace, those patterns and systems I adored would continue on.

I observed and probed my colleagues, often asking what they would do in devilish dilemmas, what their dream jobs were, and what their worries were while working at their desks. What I discovered is that I found myself among the most interesting and varied group of people I had ever encountered. Sharon the make up artist gave me tips on make up, Monica from Spain and I would talk about literature, and I once accompanied the very Dutch Anne and Samantha to their weekly McDonalds lunch trip and ate our hamburgers while the pounding of hardcore through speakers and subwoofers violently rammed my sensitive artists’ heart from all sides. I spoke about the use of art and why it shouldn’t be free to Karim, who also worked at his father’s pita bread factory on the side so that he could afford his outfit that cost as much as a whole week of my pay. I found out that the animal caretaker is getting married this year, that the musician’s dreams of making music have died, and tried to understand the conversation between the biologist and the accountant but couldn’t follow it due to my own background. As Gerda the artist I naturally delivered my own contribution to this colourful group. In the hours that we spoke I was exposed to an enormous amount of input, and in the hours that we were silent, my mind ran with the most fantastic and ridiculous ideas, most of which I executed the minute I got out of work. In the meanwhile, I collected my staples in a glass jar to remind myself, in some glorious future, of this period of my life.

The jar has since been filled and the project at the office is over. I’ve been at home with many ideas for works and projects, both running and on the drawing board. Once again, I’ve been diligently typing up job applications for every position you could think of, and sometimes find myself nostalgically thinking back to my academy days. It was a fantastic place, buzzing with possibilities, colourful exuberance, and colourful people. But if there’s one thing I learned in the last year, it’s that the world outside of the academy is just as colourful and that ideas don’t stop—no matter where you are. So I might just go for office-plant-caretaker, furniture tester, chauffeur of a karaoke taxi, bartender at a swimming pool, hotel room cleaner, or find myself some other fascinating occupation. And then, make work or write texts about it. I think that would be fantastic.