Even Nazis needed a vacation from time to time. True to the nature of their regime, they met this need with great grandeur. On the island of Rügen, one monstrous project erected for the ordinary man remains: Prora. The walls are covered in graffiti by young Germans practicing their English. Although thousands of its windows have been smashed, it seems that the structure of Nazi vacation fun is indestructible. Prora now resembles a mega jail, where people in bathing suits were herded together.

The resort was the world’s first mega project for affordable mass tourism. Kraft durch Freude (KdF,) the Nazi department for recreation, commissioned the resort to be built between 1936 to 1939.

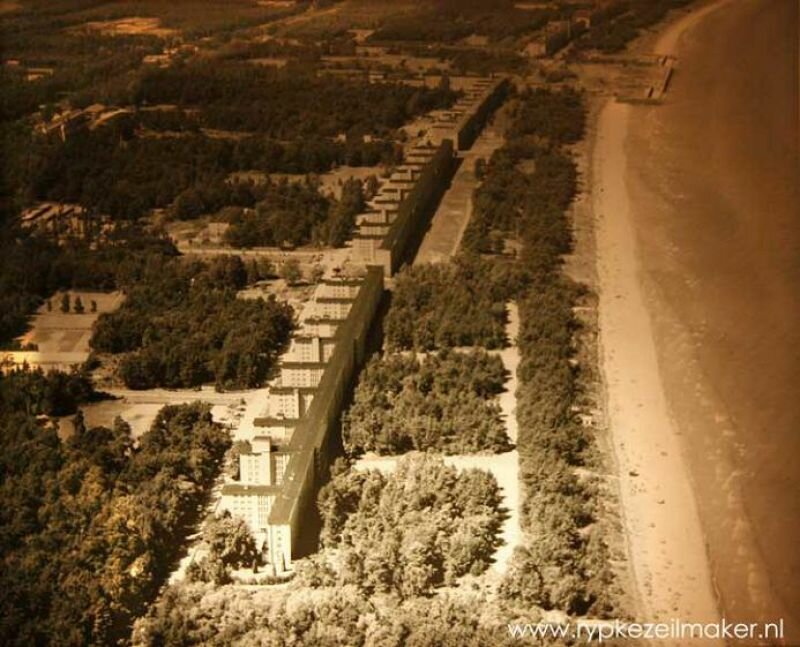

Between Binz and Sastnitz, five kilometres of grey megalomania is wacked in the face of the visitor. Even the waves of the Baltic Sea are cast in a grey veil by the shadow of Prora. A thin edge of shore is covered by vacant apartment blocks, each half a kilometre in length: the remnants of an event hall, sporting facilities, a docking station for the KdF’s cruise ships. Prora offered 10,000 labourers a room here, each with of view of the sea.

The Nazi department of recreation was strikingly modern, being pioneers in both cheap mass tourism and marketing. Recreation was promoted as a ‘lifestyle’ beneficial to health by advertising scarcely dressed beautiful people to promote the products of the KdF. And they were successful. Just before the war, in its glory days, the KdF provided the vacations and cultural outings for 80 million civilians. Even the ‘Volkswagen’ was a KdF initiative to stimulate daytime recreation.

Vacationing in the healthy sea air was supposed to make the people stronger, for the sake of the economy and the regime. “To run a great political vision, I need a strong nerved people,’ said Hitler, as he lay Prora’s first stone. Thanks to the German invasion of Poland in 1939, little became of vacation plans to Prora, and it became a military hospital instead. Victims of the allied bombing of Hamburg in 1943 were given shelter there. And from 1945 until the fall of the Berlin wall, Prora served as headquarters to the Nationale Volks Armee, or the DDR army.

The local government has been stuck with the ruins of Prora since the German unification. Three of the half kilometre blocks were sold to project developers, to keep themselves from the expenses of upkeep. But these new owners, too, wrestle with Prora. The Nazi retreat is falling steadily into decline, and so the main inhabitants of these buildings are bats and colonies of swallows.

Ironically, its monumental status is partially the reason for its decline. Prora became a nationally protected memorial thanks to the lobbying of artists, historians and architect through Stichting Neue Kultuur. Thus, the Bundesrepublik is extremely critical of any large-scale refurbishments. Many of the developers also misjudged the amount of investment it would take to develop the colossus.

Because no one wants to touch Prora, the Nazi vacation colossus has assumed many temporary functions. Blocks of apartment buildings have been used by artists as studio and presentation spaces for years. In 2000, Neue Kultur founded Documentatiesctrum Prora in Block 3. This centre keeps the history of Prora and the KdF alive through exhibitions and historical research. The NVA-Museum, located next door, relives a bit of DDR-nostalgia in a Goodbye Lenin sort of atmosphere.