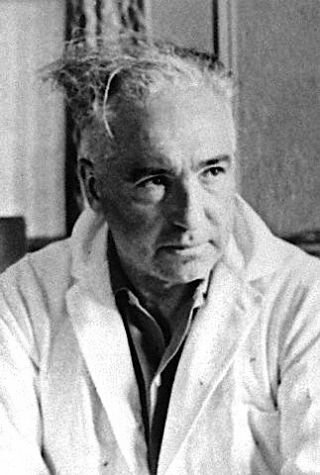

During her first chemistry lesson with Professor Allio, who has a huge angioma covering much of his face in a way that made it difficult to guess which was the birth mark and which was the unblemished skin; she learnt the transition of water in different phases.

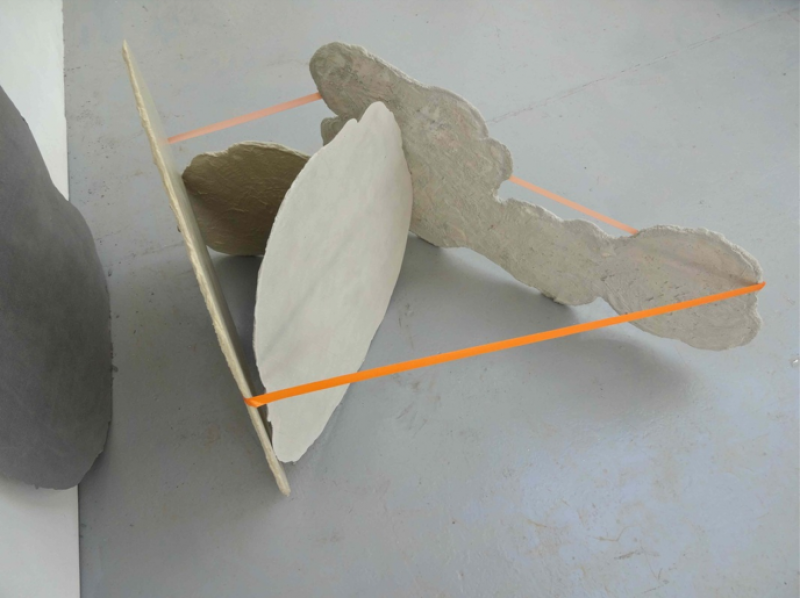

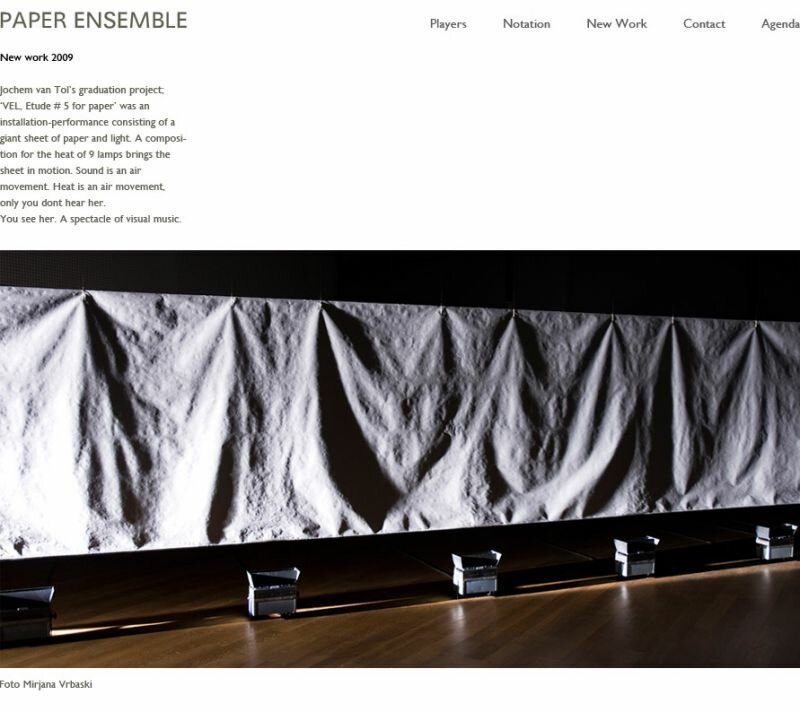

The transition takes form between solid, liquid and gaseous states of matter, and in rare cases, plasma. Those different states of matter suggest the process of creativity typical of an artist, where ideas often start as blurry images and finish with a solid body of work.

This blurry image, roughly organic, can be compared to an intangible substance almost with the consistence of plasma,in terms of a unique condition of matter, which doesn’t have a definite shape or a definitive volume unless in a container.

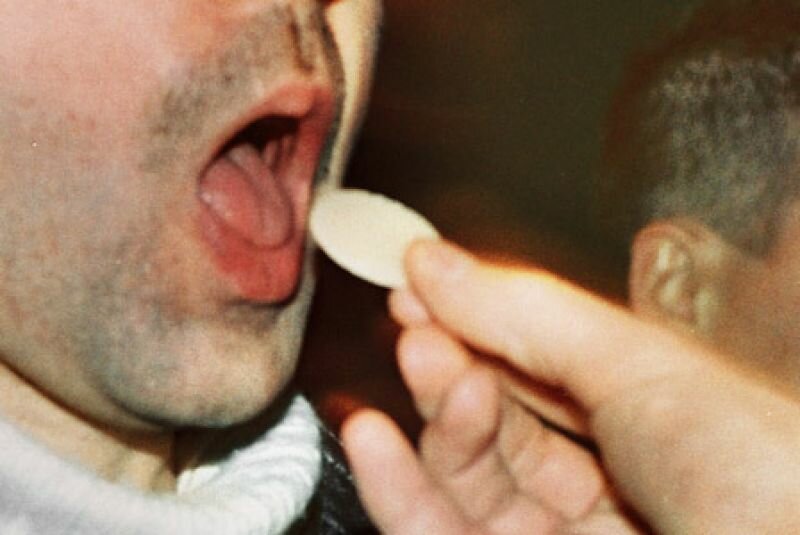

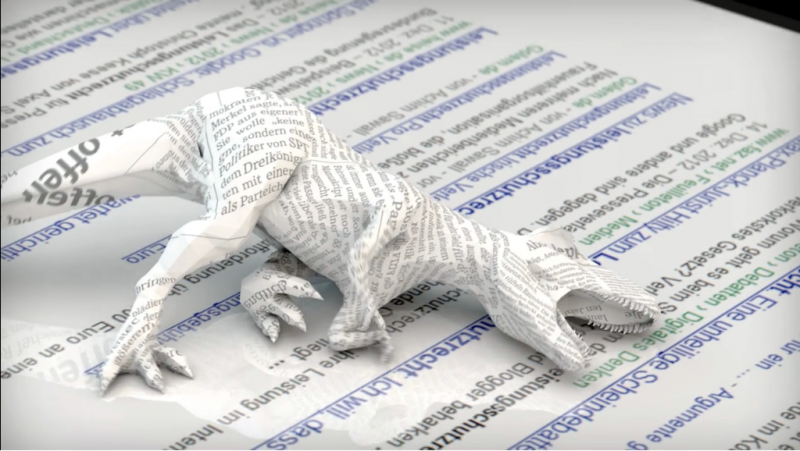

In the paranormal field the ectoplasmic phenomena is associated with hauntings and it is understood that it has been a slime-like substance excreted by mediums during trances.

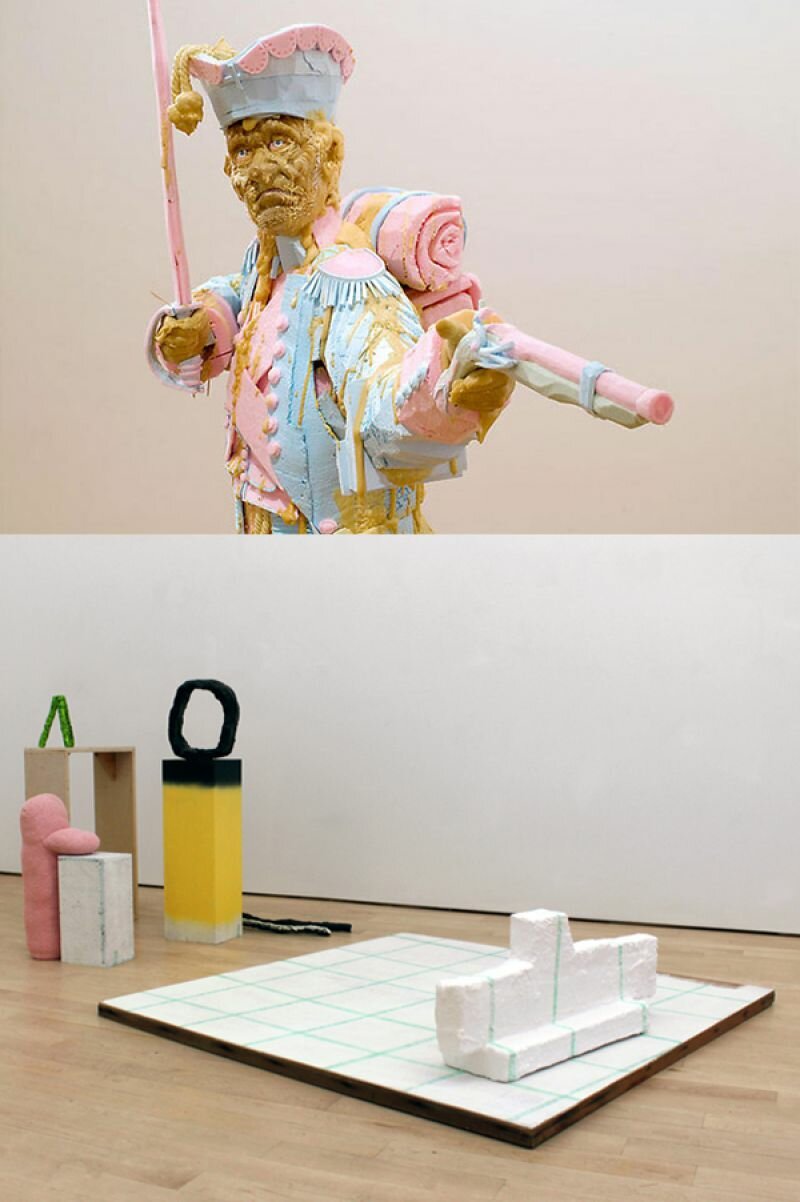

All those transformations from one matter to another could have several affinities with the gestation of an idea until its materialization: during the process of creativity, an artist passes through several complex stalemates: she gropes, she calls herself to question, she can get obsessed, she can switch back and forth between several ideas and she can get truly confused. Exactly during those transitions, the work starts to take form, even if it’s just a rough sketch. This itinerary, which fluctuates through several states of mind, gives an essential mobility to the concept.

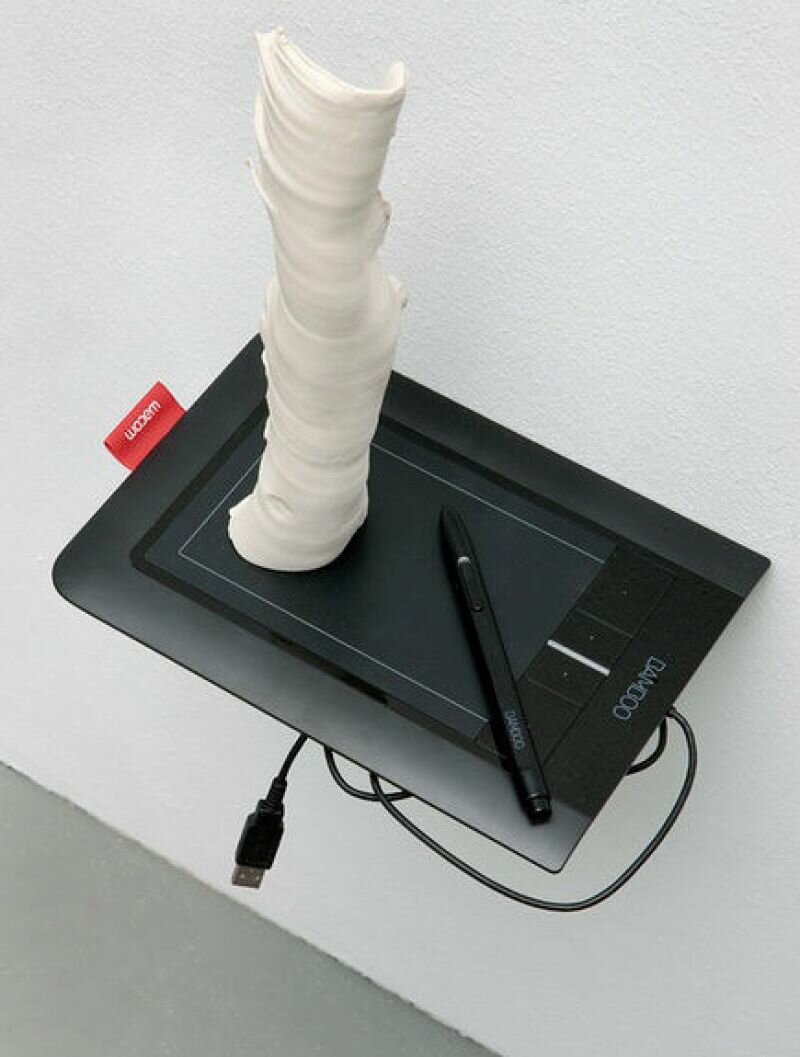

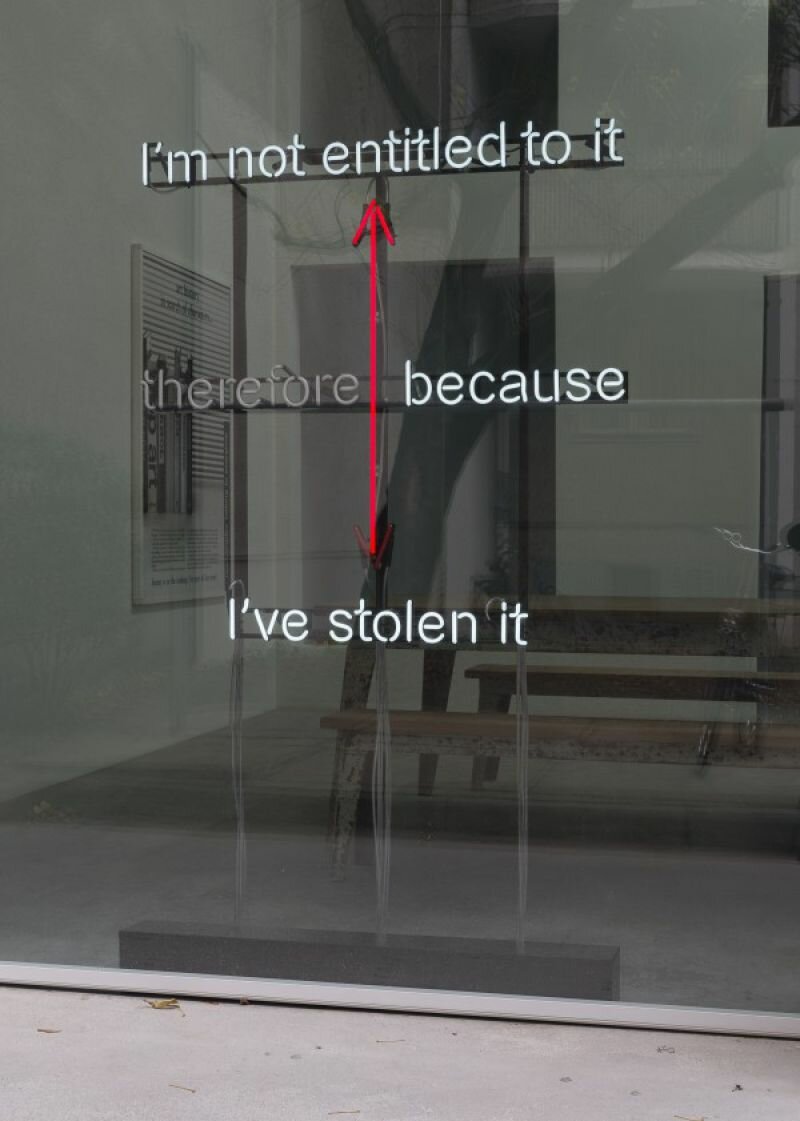

Nevertheless each artist has her/his own way of experimentation and unfortunately, what it is visible is always the final stage and a final body of work rather than the uncertainty and the confusion. The backstage of most of the artist’s studio is hermetic and makes it almost impossible to deduce any linear theory about the experimentation. Can we therefore say that maybe artists and mediums have something in common because neither have any rational explication that can explain their conception?

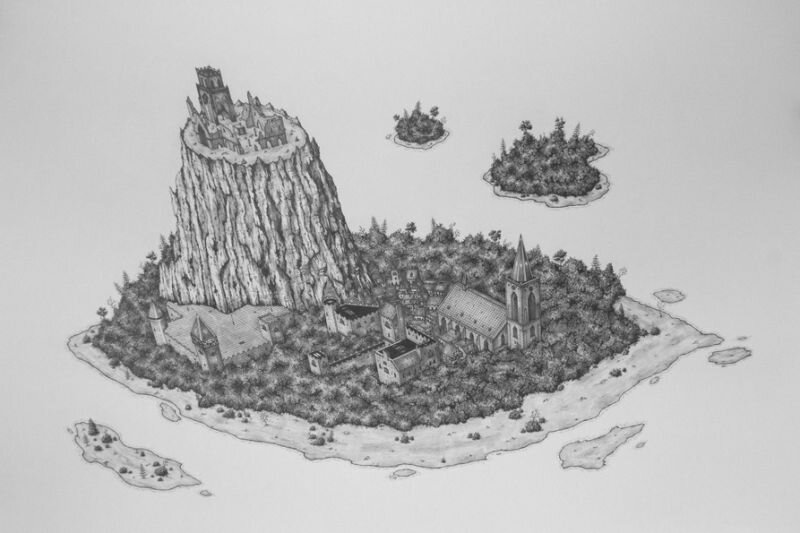

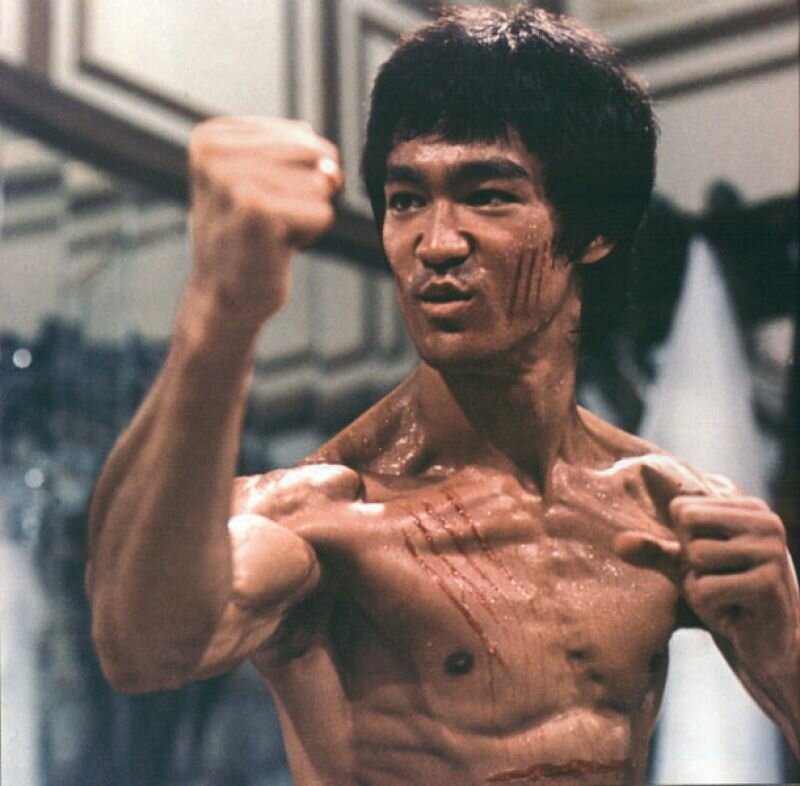

Bruce Lee says “Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

Being shapeless means for her not being stuck on a fixed point, position or protocol but rather avoiding the safest places and resisting formalisation. Bruce Lee’s words makes her pensive. As an artist, she feels that she has in her hand a double-edged sword that sometimes she doesn’t know how to handle. She feels split between a certain free form daily life and the duty to follow a strict discipline. She knows that she needs some routine to progress in her work but at the same time she is afraid of unnecessary repetitions. Nevertheless she repeats in her mind, almost as a mantra, some statement in which she wants to believe: make mistakes, make risks happen, learn in a wrong way, be convertible, don’t care about ending points, use your non-knowledge as a starting point, use raw feelings and affirm you are an artist, even if people don’t truly trust you when you say that you are an artist without being a painter.

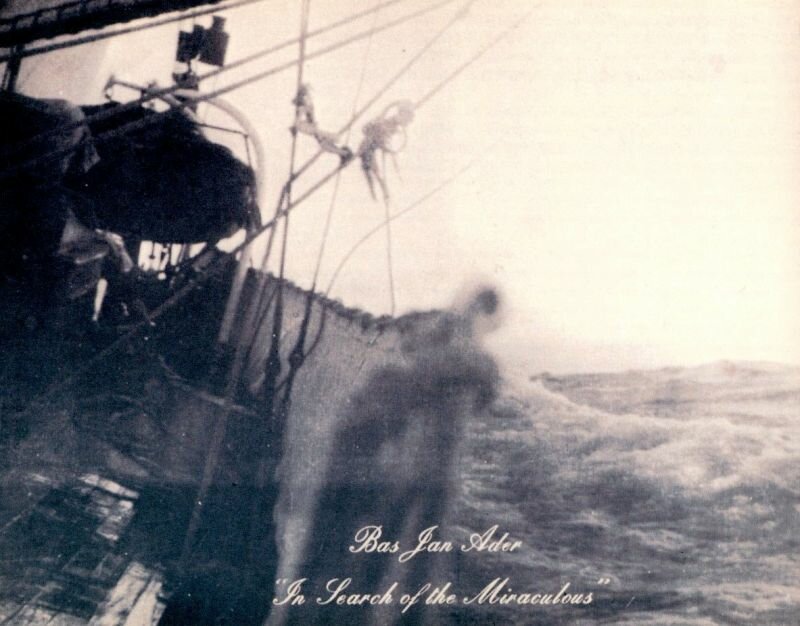

She wonders, are they the advantage points of not belonging to any pre-packaged society category? She wants to believe in this freedom in a conscious manner by cleaning up all stereotypes, a desire which recalls the opposition repeatedly mentioned between Scientific’s rationality and artist’s irrationality. When she is falling asleep this feeling becomes almost a vertigo, especially if she is sitting in a chair trying to resist sleep. When she is in this state, between being awake and falling asleep, she experiences a certain floating sensation that is like being physically in a place, which is notcompletely a real place. From her chair, her wall looks too aseptic, almost like that greenish tone typical colour of a waiting room. She feels strange, balancing like the bubble in the tube of a spirit level that is trying to stay straight.

This uncertain condition of reverie between a state of being and state of non-being, has been a crucial stage in the history of chemistry. In the early 1860s, the German organist chemist Friedrich Kekulé awoke suddenly being able to discern the ring structure of benzene because he dreamt of a snake swallowing its own tail. Similarly, Dimitri Mendeleev, chemist and inventor who created his own version of the periodic table of elements, after three days and three nights without sleep, fell into a profound slumber, from which he awoke eventually able to see the pattern in the form of a table of regular properties.

Liquid, equilibrium and dream are three mysterious elements indirectly connected. A transparent liquid can hide a strong invisible power, a poison, a drug or a magic fluid. Equilibrium is highly related to our consciousness or awareness consider that in medical terminology we experience and talk about as labyrinthitis, an infection that can affect our physical equilibrium, which is in turn regulated by a special liquid in our ear. It is a mechanism that can be compared to the functioning of a spirit level. Dreams are dreams and they don’t have any limits, and it is interesting to remember that for a long time, alchemists speculated about what material dreams consisted of and without any evidence, they thought, “dreams were made out of some kind of gas, cloud, or superfine fluid, subject to rapid diffusion,but also capable, as is a gas, of gathering and lingering.”