Robert Cervera is an artist born in Barcelona and living and working in London.

1000 Things is a subjective encyclopedia of inspirational ideas, things, people, and events.

Read the most recent articles, or mail the to contribute.

Robert Cervera is an artist born in Barcelona and living and working in London.

There are human instances in which we get quite close to understanding the language of materials.

There’s the hoe plunging into the soil: crumbly in its first inches, then more pliable as we reach the moist underneath, then almost solid in the fresh darkness of laborious earthworms. Tchak and the worm is two.

There’s the bundle that a wood seller makes with logs or sticks; the line-like tension of the rope that seconds ago was sleeping amorphously in his pocket.

There’s the moment in which you sillily slightly slice the skin of your hand and for a second you don’t know what the physical bill will be: a momentary white line, a surge of blood, anything in between.

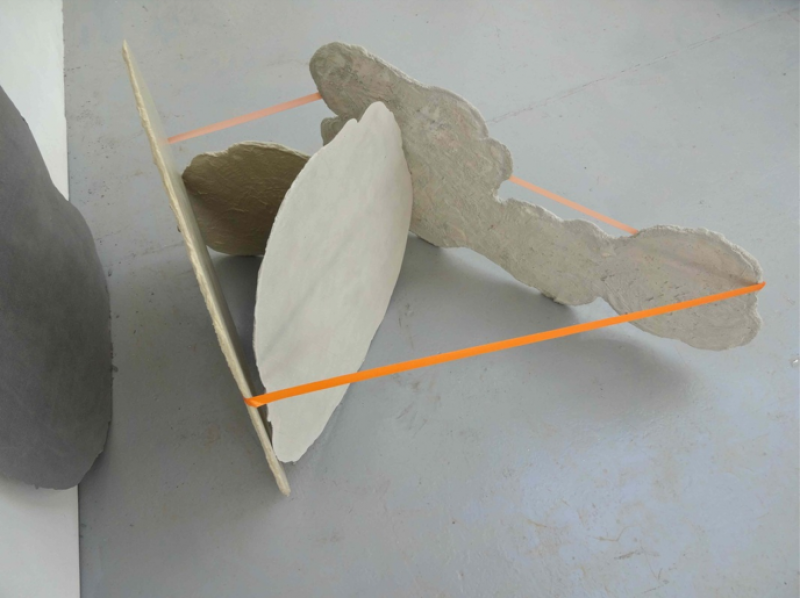

There is sculpture in those things. And there is a chance those things may be in a sculpture. And the sound they make – a sound in your mind – sends us back, like a sonar, an image of the world.

Materiality and human agency talk to each other. Squeeze, slice, drench, chafe, wedge, pat. Haptic marvels. How things feel, what they make us feel.

(No distinction can be made between humanity and materiality, Hegel and Bordieu would say. We humans are materials which create other materials which then redefine us. The things we make, make us.)

The unbounded nature of the universe comes into the discussion. Matter flowing, going everywhere, and us chasing it, telling it to go this or that way, to stay in line, to wait in groups of four, of sixteen, of sixty-four.

We try our best to make the uncountable countable, to mark limits and give shape. We end up frustrated and beguiled at once by its unruliness, charmed by its oozing.

(Is it possible that we contain matter in the paradoxical way some cage birds, to better admire their flight?)

I am fascinated by that and also by the unexpected occurrence, the providential blunder, which I take to be one more chapter of our ongoing dialogue with materiality.

Concrete is not squeamish: it drinks anything it can, all through its life.

I offer my hand to the thirsty mass and can feel it licking my moisture with a dry tongue. I pat it twice.

There goes my salty sweat, entering the capillary system of the concrete and messing with its chemistry. The grey giant takes me in.