They were stern, yet loving. He was never short of food, though it was rarely ever tasteful. Finishing off his plate was such a lengthy process that the last bites were usually cold. Nothing out of the ordinary happened while he played on the streets. Every now and then, his report card showed a fail. There was only one thing that worried him. Worry might be too strong a word; rather, something had occurred to him. Something must have gone wrong somewhere down the line. Something he could not grasp. No curse had befallen him, yet no blessing either.

The teacher often arranged the students in a line. After all, line was the most practical way to manoeuvre a group from A to B. From class to the schoolyard for recess, from the street to the swimming pool for swimming lessons. It was fun standing in line because at least you knew something unusual was bound to happen, unlike when sat your desk. But standing in line did not always foretell a pleasant event. If ever the class was suddenly asked to stand in line, one could rest assured that at the end of the hall you’d be awaited by a white coat holding an injection needle. And without fail, he was always the first to be called. To bare his arm, to stretch open his mouth. It took a while for him to notice. Initially he believed fate to be at work, until he began to realize that maybe there was something actually wrong with him.

At home and leaning over a never-ending plate of food, he began to inquire. His father took him aside, which was in itself a foreboding act. It must be something from the adult world, the scope of which was difficult to discern.

‘Thousands of years ago, in another country, the alphabet was invented. We’re not exactly sure why, but they decided that the letter A should come first. And it’s been like that ever since. Don’t think that the A will ever move to another spot in the alphabet. This is one of the few things in life that you can be certain of. Just like the A will always be the first letter of Aarsman. That’s why an Aarsman is usually at the front of a line. At least, when lines are arranged in alphabetical order. Of course, there are many other names that begin with an A. But, think about it, how many names do you know that begin with two As? That’s the reason Aarsmans usually are called up first. There may be times when this is unpleasant, but usually itturns out to be quite useful. Like when Sinterklaas comes to school, and you’re called up for presents. For example.’

Father saw wrinkles of thought forming on his son’s forehead.

‘You’ll have to bite the bullet, but you’ll see, in due time you’ll only ever want to be first. Why do you think we have sayings like the early bird catches the worm? And how about don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today?”

Holy smokes, Hans Aarsman thought. The name came from his father. And he went on and on about how wonderful it was to carry that name. But indeed, if something pleasant was to happen, the Aarsmans were always at the frontline.

“The early bird catches the worm.” And: “don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today,” He repeated the idioms, tasted them, they lay ready on his lips. They came in handy if ever at a loss of words. He added a new one: “First come first served.” Some seemed to have been invented especially for little boys who had to stand at the front of the line against their will. But strangely, on his quest for new idioms, he encountered many that declared the very opposite. Like: “Haste makes waste,” and: “The first shall be the last.” In fact, idioms seemed to go in every possible direction. “Waste makes haste.”

The idioms were still contradicting themselves when one night it wasn’t he, but his brother, who was the last to finish his plate. He noticed this because the last bite to disappear into his mouth was not cold as usual, but in fact, lukewarm. Without truly deciding to, he started upping his tempo. For the first time, he saw the advantages to being fast. If something was to happen, he might as well get it over with immediately. The way he saw it was, when his classmates were standing, shivering standing in a row, he’d already had his injection. And while the others were still being examined, he could leisurely recline. Before he knew it, he’d gotten used to being a double A’d Aarsman.

And then things changed. He noticed how nervous he’d turn when not standing first for inoculations and dentists. He sped behind his desk the very moment he returned from school to do his homework. He scarfed down the food on his plate. With everything he did, he though: if it has to happen, then let’s have it done at once! And so, until this very day, he speeds through all, both the fun and the not-so-fun in record time. A birthday party? Don’t stick around too long. Don’t overstay your welcome. Should a bill or form arrive in the mail, Hans Aarsman will fill them in that very night and toss them into the nearest mailbox. Never owing anydebts. His name is always at the top of a list. There’s no avoiding that man! No group manifestation without his name at the top of the list. And that’s how I succeeded in being able to have my say right here. That’s one thing, but there’s another undeniable aspect to the last name.

It happened in the biology classroom. The first years of middle school were all about the body: blood circulation, digestion, the nervous system. Then came the other mammals, from big to small, from whale to mole. And then came the cold-blooded animals, the frogs and the crocodiles. He must have been sixteen when they came to the multicellular organisms. After which came the parasites, organisms that couldn’t sustain life on their own and needed a host to survive. This could be a plant, an animal, or a human. They crawled in, started their feeding, and laying their eggs. Ringworm, lintworm, hookworm. How they came from pigs, how cross contamination occurred. One by one, the teacher drew them on the blackboard. His thoughts were wandering – there were quite a few parasites to be named – when the sound of his classmates jeering jolted him back to reality. The teacher had drawn a creature on the board. A moon-shaped staff. Was it hairy? He doesn’t remember, but can clearly recall the title it was given: Aarsmade (n.b. translated from Dutch into: Arse Maggot.) The jeering was deafening, and they were pointing… at him. The precise nature of the aarsmade is still not entirely clear to him. When the teacher understood the cause for the uproar, she quickly wiped the drawing off the board. Never again was the aarsmade spoken of. By the teacher, that is. His fellow classmates eagerly entertained themselves for weeks, conjuring variations of his last name. How utterly inspirational nature can be. Go ahead, try it, it’s not hard to come up with a few yourself. At the time, buttguy and assdude were by far the most successful. Don’t react to their taunting, he had resolved, and he didn’t.

When the Americans started napalming Vietnam a few weeks later, man, plant, and animal were burnt to a cinder. The school was so caught up in these events that the creature and his unfortunate namesake were cast into the oblivion. Still, he was slightly fearful that the aarsmade would rear its head during examination week. What if one of the questions was: name three human parasites? But the teacher was sure to avoid, at all costs, any question that concerned that possibly hairy, moon-shaped little staff.

These days I sporadically hear a nearly inaudible chuckle when phoning an institution, or I’ll see the corner of a mouth turn upwards at a counter. The most spectacular would be the time I reported the disappearance of my bicycle. The policeman on duty pulled an earnest face: “I can’t believe they never told you that it hardly costs a thing to change your name! A strange name will even be changed for free!”

But I’d never do that. Above me and below me, the phonebook lists a plethora of Aarsmans. Do I abandon them? I know them all. They’re all descendents of my grandfather. Until recently, that is. In the 80’s, a small migration took place. Dozens of Aarsmans from outside Amsterdam moved into the city and connected themselves to a phone line. They, too, had understood the benefits of alphabetic order.

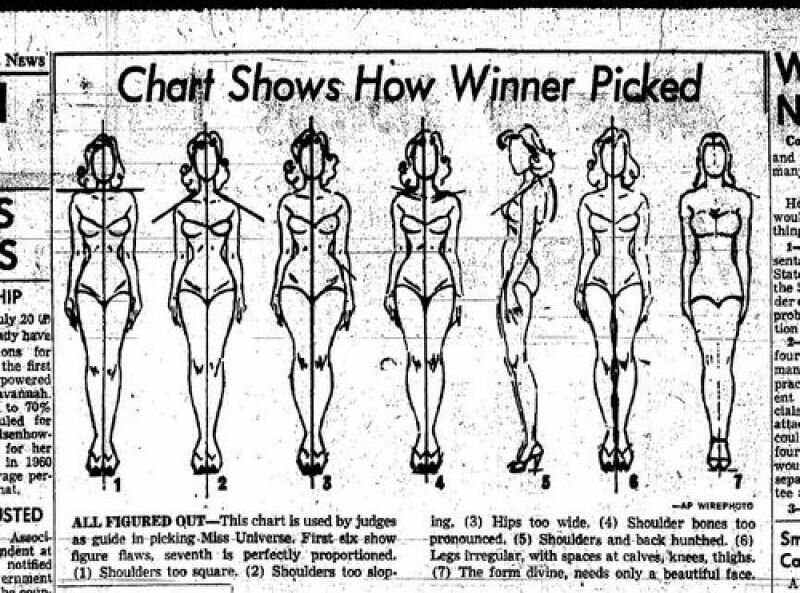

A few months ago, the newspaper wrote of an Olga Aarsman who competed in the miss Ajax pageants. She’s no cousin of mine, and she didn’t win.