The first time I noticed how interesting the effect of name giving was to me, was during my first year at the Rietveld Art Academy.

'Create a panorama.' That was the assignment.

As a perfect example of my generation I didn't find out how to actually make a panorama, instead I went to see the dentist and asked him to make a frontal x-ray of my teeth. I printed it on an A3 and thought: this is a panorama and I'm going to call it 'City by night'. The text belonging to an image can unlock or represent an entire world. The tension between the word, its meaning, the image and its visibility can serve as a playground. Marcel Duchamp referred to the function of the title in arts as an invisible colour.

Sometimes the invisible is a promise. Like a pregnant belly. What's inside, will receive a name. It's the cherry on top.

Today I want to talk about names because life begins with having a name. I will introduce name giving with a juicy piece of gossip. I thought I had reached closure in my first sad love story when I was eighteen years old. But the final scene came later.

I rebooted my computer and logged on and off of Facebook but the site was not the problem. By naming his daughter Annelein he had managed to create a connection between him and me.

Of course we are not really connected. Of course it's only a name. Every sane person knows there's no harm here. Then why did it feel so poisonous?

The gesture is so much bigger than the actual event. It's an exercise of power.

‘What’s in a name? That which we call a rose. By any other name would smell as sweet’

The North American Indian treated his name as a part of the self. His name is just as important as his eyes or teeth. Malignant use of his name is as harmful as hurting his body. There are Aboriginals who keep their names a secret to protect themselves against evil. There are Indian tribes that demand their members to change their names after one of the members has died. Some Indians have to deserve their name, until that time they are called 'boy' or 'girl'. Other Indians will never say their own name out loud when they're close to a river because the water can take away their soul and evil will get hold on them.

People have names, art works have titles, products carry a brand, plants and animals have a terminology.

If I remember correctly there are Aboriginals whose names refer to natural phenomena. The name Karla could, for example, mean 'fire'. When that person dies, they never use that name again and have to come up with a different name for 'fire'. That's how their worldview is under constant change. The associations connected to the word 'fire' will have to be reborn.

In theory I appreciate a worldview that claims authority in this way. Not because I am willing to view the world in the same way and not because I would be able to, but because you never know when Karla is going to die.

Some people speak on behalf of the law; others speak on behalf of art. There's always a connection between claiming power and the usage of names. Americans tell me: 'Hi! What's your name? Annelein? Oh hi, Annelein. Nice to meet you Annelein.'

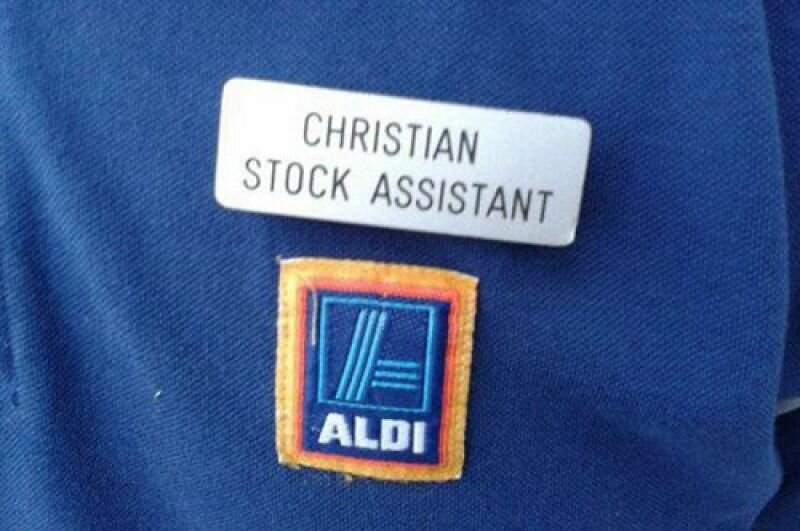

A friend of mine thinks it's disgusting that cashiers are forced to wear nametags. It makes them submissive.

You can tag someone and reduce him or her to a notion. Or, in the case of products, turn their name into a concept.