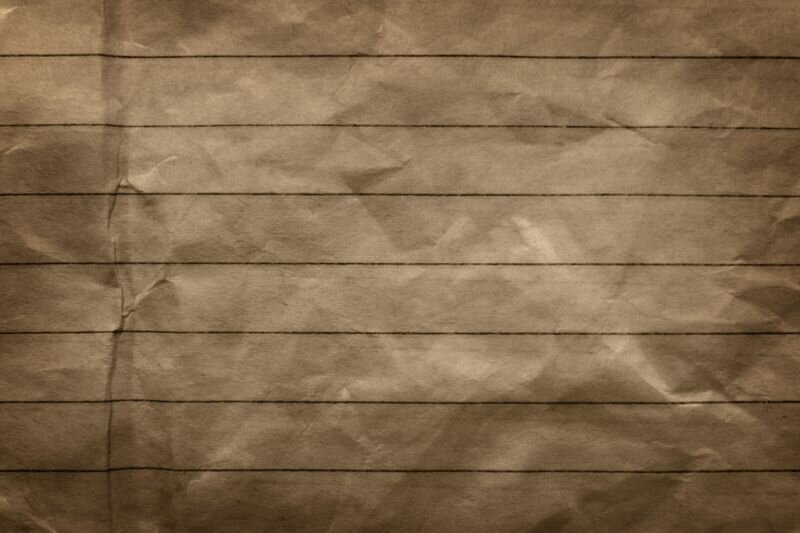

Paper is vulnerable. Every form of contact with the world affects its condition. When you place a hand on it, it moves. A subtle bumpiness, a slight stain. Even if paper is lit by the sun, if water drops on it, if the wind lifts it up or if it hits the floor, it will preserve traces thereof.

Paper emblematises the power of victimhood. By itself it would never contrive to undertake anything, but it will remember and showcase everything it undergoes. Paper is passive but vigilant. Its strength lies in its capacity to take what comes and testify, to proclaim the transience of existence. As soon as the three-dimensional world collides with its two-dimensional membrane, the latter points this out.

No wonder paper is the quintessential disposable material. We wrap food in it, wipe our mouths, sex organs and arses clean with it. Paper desires to be tainted. It gives who fouled it a grateful sense of cleanliness, a proof of usage that cannot be disavowed. It requires minimal effort to appropriate this defenceless material. Paper lends its user a feeling of careless might.

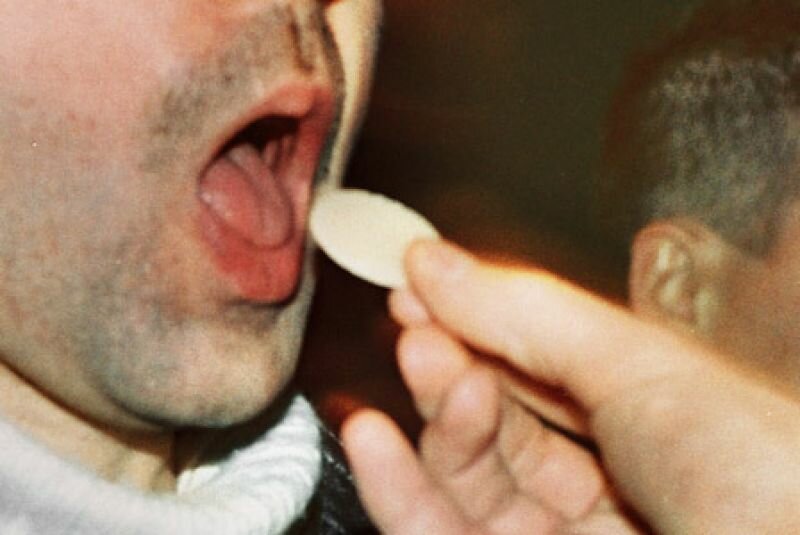

All the more does it impress when paper is cherished: if it is framed behind glass, protected in a vitrine or a vault, if it is handled with little white gloves. Because it carries something that somebody wants to preserve: promises, inventions, signs of life from a bygone time. Precisely because of its flimsy brittleness can paper be endowed with unimaginable status. Is it a coincidence that our contracts and bank notes are made of paper? That the body of Christ is eaten in the shape of the host, a coin of consecrated edible paper? That a present does not receive its ceremonial value until it is wrapped in gift paper?

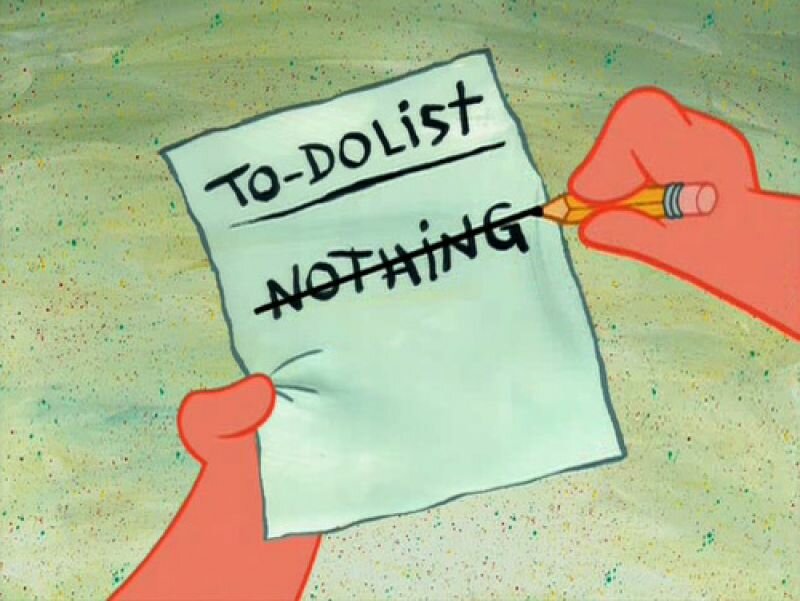

Blank paper is sometimes called ‘virgin’. Few materials can appear as immaculate as a fresh sheet of paper. Such a radiant, new surface can be a promise, but also pure intimidation. It is not for nothing that an empty paper is the symbol of writer’s block. The white is locked. As an unconquerable fortress, it waits. Bare and naked as an unploughed field. What should be sown? Once started, there is no way back.

There is a drawing that I often think of, even though I only know it through a description I read somewhere. It is a drawing by Bas Jan Ader. It consists of a piece of paper on which numerous attempts have been made at drawing, which have been erased again and again, until only an extremely thin film of paper remained. An ode to failing, to the vain endeavour of materialising a conception of the imagination. Although theoretically, all is possible on paper, in practise it mostly amounts to very little. Only the promise persists forever.

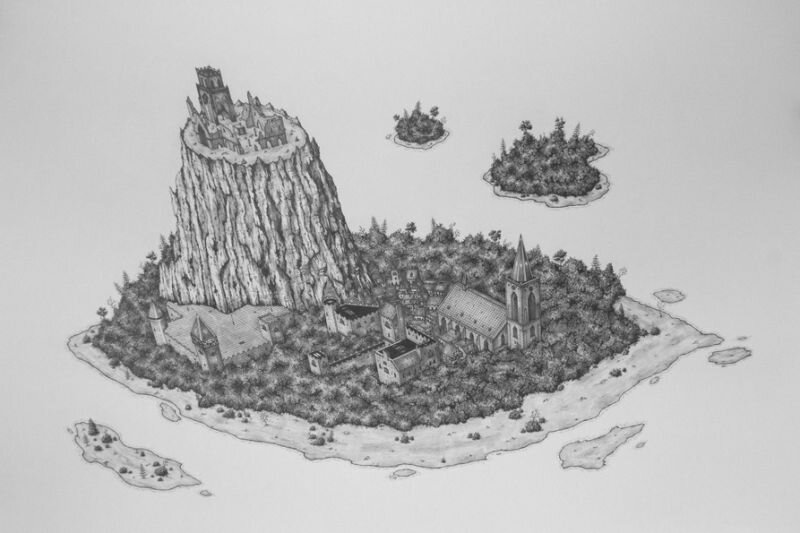

There are two antipoles among draughtsmen. There are the cautious perfectionists, who keep the paper around their drawn traces as pristinely white as possible, and the aficionados of stain and crease. Artist Rik Smit belongs to the first class. In his gigantic panoramas, drawn with impeccable precision and often from a bird’s eye perspective, the paper in between and around the lines is tight and gleams with sparkling white, as if no hand has ever touched it.

During the making of a large drawing Smit sometimes goes through as many as 12 rulers. If the plastic of the ruler becomes dirty from the graphite of the lines Smits draws with them, it starts to leave a haze on the paper. That means it is time for a new one. Smits uses about a hundred rulers a year. For the sake of convenience he usually buys the entire stock at Bruna. If the weight of the hanging paper causes a dent in one of his enormous drawings, Smit steams and irons the paper until no traces remain. Kim Habers, in contrast, tears, creases and cuts her paper. Her sometimes space-filling drawing installations look like solidified disasters.

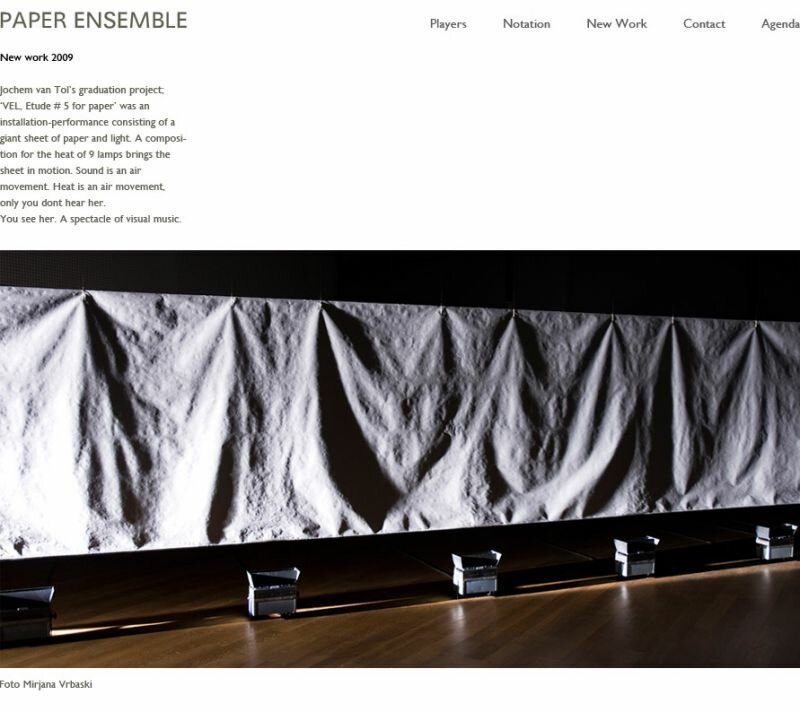

Johem van Tol made the sensitivity of paper itself the theme of his installation

VEL. Etude # 5 for paper (2009). He hung a huge empty sheet of paper facing a line-up of lamps that were continuously changing in temperature. Under the influence of the heat, the paper starts to slowly expand and ripple, causing a constantly different, abstract image to emerge. Van Tol knows the kinetic properties of paper like no other. He even formulated a musical composition for paper, which he performs with his Paper Ensemble. During their concerts the Paper Ensemble make different kinds of paper crackle, whine, lisp and hoot.

One of the most beautiful qualities of paper is its capacity to propel the imagination at full force with minimal means. The song It’s Only a Paper Moon (1933), performed among others by Ella Fitzgerald and the Delta Rhythm Boys, allows itself to be listened to as if it is sung by a drawing itself:

Say, its only a paper moon

Sailing over a cardboard sea

But it wouldn't be make-believe

If you believed in me [LINK:

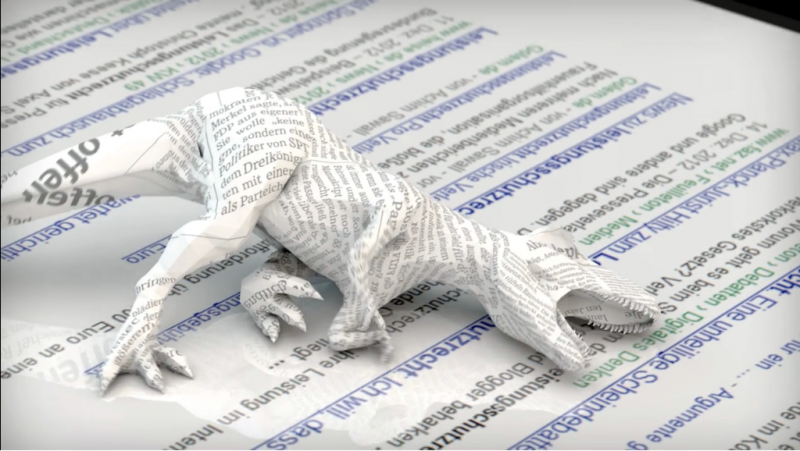

Some people think that the age of paper draws to an end now that the world is digitalising. The digital animation

Paper Age (2013) [LINK:

http://www.kenottmann.com/2013/05/blog-paper-age-fur-deutschen-webvideopreis-2013-nominiert/] by Ken Ottmann shows how the powers of a dinosaur from folded newspaper collapse when, in the midst of a newspaper landscape, it encounters a huge tablet. It walks onto the screen, falls down, and dies. However pretty these images are, the paper fetishist mainly notices how fake the movements of the digital-paper dinosaur are. As it moves its programmed limbs, the elastic pixels bend back and forth most limberly, whereas real paper would fold and crumple. Thus the video unintentionally shows the opposite of what it wants to demonstrate. Precisely the fragility of paper is the secret of its magic. As long as we have bodies, we will long for materials that are as vulnerable as ourselves.