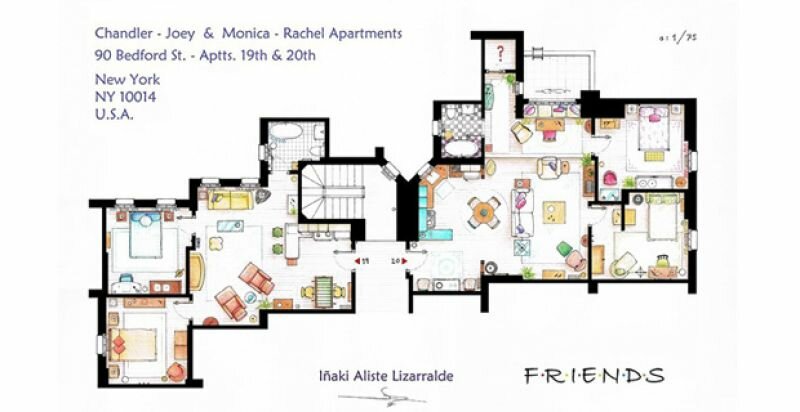

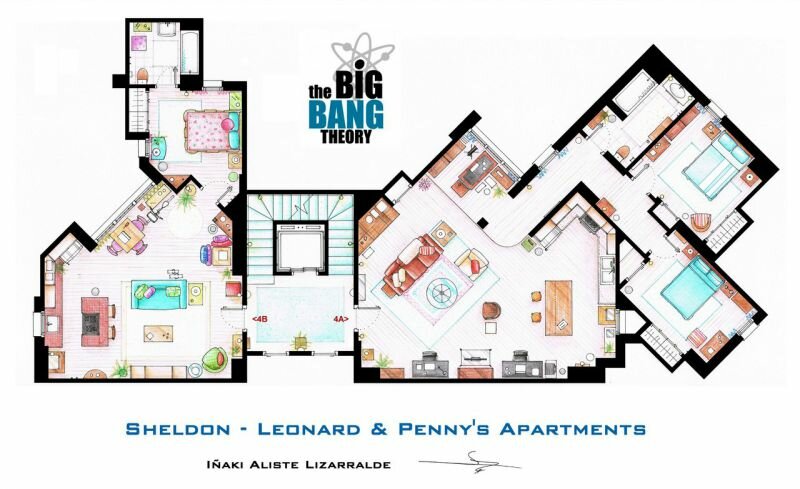

The Spanish interior architect Iñaki Aliste Lizarrald draws detailed maps of houses from TV series and films.

From Will & Grace to The Big Bang Theory to Up to Breakfast at Tiffany's: fans will instantly recognise the apartments they have so often taken a peek into. Lizarralde (42) meticulously studies the series to find out the precise location of furniture and the way the rooms are connected.

'About five years ago I started to draw the interior of Frasier's apartment,' he writes in an email from Azpeitia, a small town in the Spanish part of the Basque region. 'I liked the series and the apartment, which I wanted to analyse. Then a friend asked me if I could draw a map of Carrie's flat from Sex and the City. That's how this got under way.'

Lizarralde claims he isn’t a complete tube-addict. 'My own taste is somewhat old-fashioned: I like Six Feet Under, Upstairs/Downstairs and Twin Peaks.' However, in order to draw up a map he goes through each and every episode, finger on fast-forward, not to miss a glimpse of the interior.

'Episodes in which the houses are clearly brought into view I study extra carefully. The most important set, usually the living room, features in every episode, so that's easy. But rooms that are more rare to snatch a glimpse of are built anew each time someplace else in the TV studios. Similarly, interiors of houses in films are often hard to reconstruct, because in films they hardly ever show you the whole place.'

Since most series are shot in TV studios, the maps don't show squares or rectangles as in a regular house. 'Films are often shot in closed sets that resemble a normal house. TV series and sitcoms, on the other hand, are made using something like theatre sets,' the interior architect explains. 'The designers use tricks to make them seem bigger. That's why many maps are shaped more or less like a trapeze. Jerry Seinfeld's apartment, for instance, is actually tiny. Yet the angles of the walls are wider than ninety degrees to make space for the actors and the interior. Additionally, these angular rooms make the room look more dynamic.'

Lizzaralde neither tries to make them into normal houses, nor does he strive for a perfect rendition of the sets: 'I translate the aspect of theatre to the realm of architecture, that's where my interest lies.'

Meanwhile, the draughtsman has become unemployed ('for various reasons'), yet he uses his twenty years of experience in interior architecture to make the maps as truthful as possible. 'I know much about measurements and proportions. In the final drawing, everything must be right: the measurements and proportions, the furniture, the colours of the woodwork and even the location of the accessories.'

The final drawings are made with a felt pen, ink and crayon on coarse drawing board. 'I find that this method is peaceful. As an interior architect I used to make digital drawings too, but to these maps I wanted to lend that sense of warmth that only handmade drawings possess.'

It costs Lizarralde around thirty to forty hours to finish a drawing. He sells his work on Etsy.com. Then he copies the whole drawing, which costs him another ten to fifteen hours. And he isn't pricy: they change owners for just forty euros.