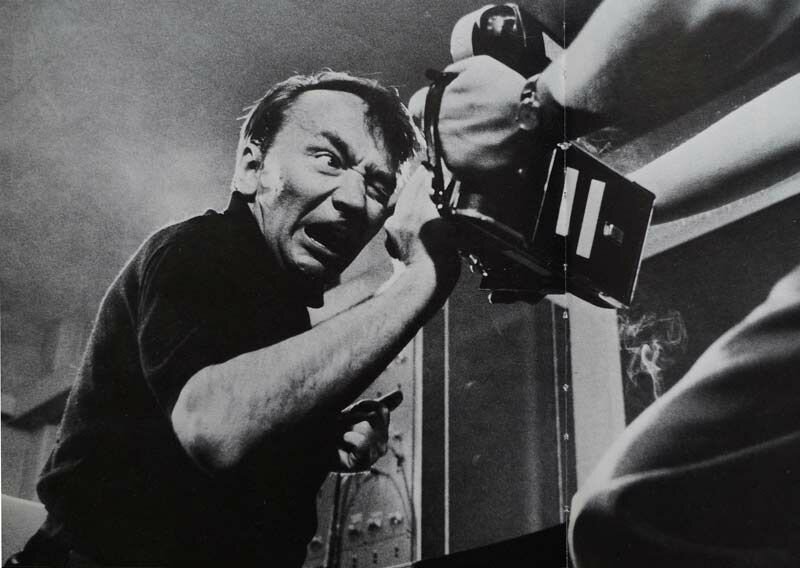

As a curious teenager I read about Thought photography for the first time, in the popular science magazine KIJK. It centred on a ‘paranormally gifted’ American by the name of who was allegedly capable of fixing his mental images on light sensitive film. The article was illustrated with pictures of buildings and street scenes, blurry, hazy and tilted, exactly like one would picture a ‘thought photograph’. There was also a picture attached of the thought photographer in action: a contorted face, head aimed at the camera. Exactly like one would expect a thought photograph to come into being.

I found it fascinating, and wholly convincing. These were, I have to add, the seventies, the times in which Uri Geller had a TV public of millions believe that he could bend teaspoons with his willpower, the times in which parapsychology could be taken seriously as a professional discipline, as far as within scientific circles. The New Age had started, with its unbridled embrace of mystique, astrology, crystals, flying saucers and whatever else is unverifiable. Previously ‘occult’ matters such as spiritism, auras, telepathy, and telekinesis seemed to have become phenomena that could be seriously studied and would even soon be explained and proved.

Telekinesis – the ability to move objects using sheer mental force, without touching. If one could assume that this phenomenon really existed, the conferral of a mental image onto light sensitive material should be one of its most easily realised forms. The defiance of gravity would not even enter into it; a subtle molecular change of some tiny sensitive layer would suffice. If the influence of even the smallest amount of light would be able to effectuate this change in the emulsion of photographic film, a concentrated thought, given extra focus by sheer power of will, then, should certainly be able to do the same.

Alas, paranormal abilities such as telekinesis and thought transfer remain unproven, and Ted Serios was exposed as a fraud even before Uri Geller (although some, of course, still challenge this). Although the New Age has really not quite ended, the idea of telekinesis seems to have almost disappeared from collective memory. As for thought photography, one doesn’t even come across the idea of it at all anymore.

That might be quite a shame, since the ability to photograph one’s thoughts is extraordinarily appealing to the artist. To take a picture not of the outside world, but of one’s inner world. Not of what something looks like, but how one experiences it. In fact, it is precisely what artists have always been looking for in photography (and all other disciplines).

For what makes photography such a difficult medium for an artist? What is the cause of the debate that is held ever since its invention, namely whether photography can be classified under the arts?

The fundamental problem, I believe, is that a photograph depicts the visible world by means of a lens and light sensitive material, enabling it to present an astonishingly accurate image of what something looks like- but not much more than that. For a real estate agent who wants to sell a house, that’s perfect, but an artist searches for something else. He does not want to register the outer manifestation, but the inner experience. An artist tries to express the invisible by means of the visible.

One could say: what the artist really and truly wants is to photograph his thoughts.

In my time in art academy, during my first skirmishes with photography, I renewed my interest in thought photography for this very reason. I did not regard it as a real phenomenon, but like a symbol, a symbol for the artist’s quest for the impossible. The ability to photograph one’s thoughts – it seemed to me a kind of Holy Grail, comparable to the secret procedure for transforming lead into gold, the potion that keeps the drinker young forever and ‘the book that renders all other books redundant.’

Thus understood, only a metaphor remains of Ted Serios’ ‘thoughtography’ – albeit a beautiful one. A metaphor of the hardly realisable desire of the artist to capture the invisible in an image.

The idea has stayed with me ever since, and I think in a certain way all my work can be regarded as attempts to break through the impossibility of ‘thought photography’.

I believe that I can even say I was successful at some moments. But that’s another story.

Paul Bogaers