Wouter Prins is curator at Museum voor Religieuze Kunst Uden

1000 Things is a subjective encyclopedia of inspirational ideas, things, people, and events.

Read the most recent articles, or mail the to contribute.

Wouter Prins is curator at Museum voor Religieuze Kunst Uden

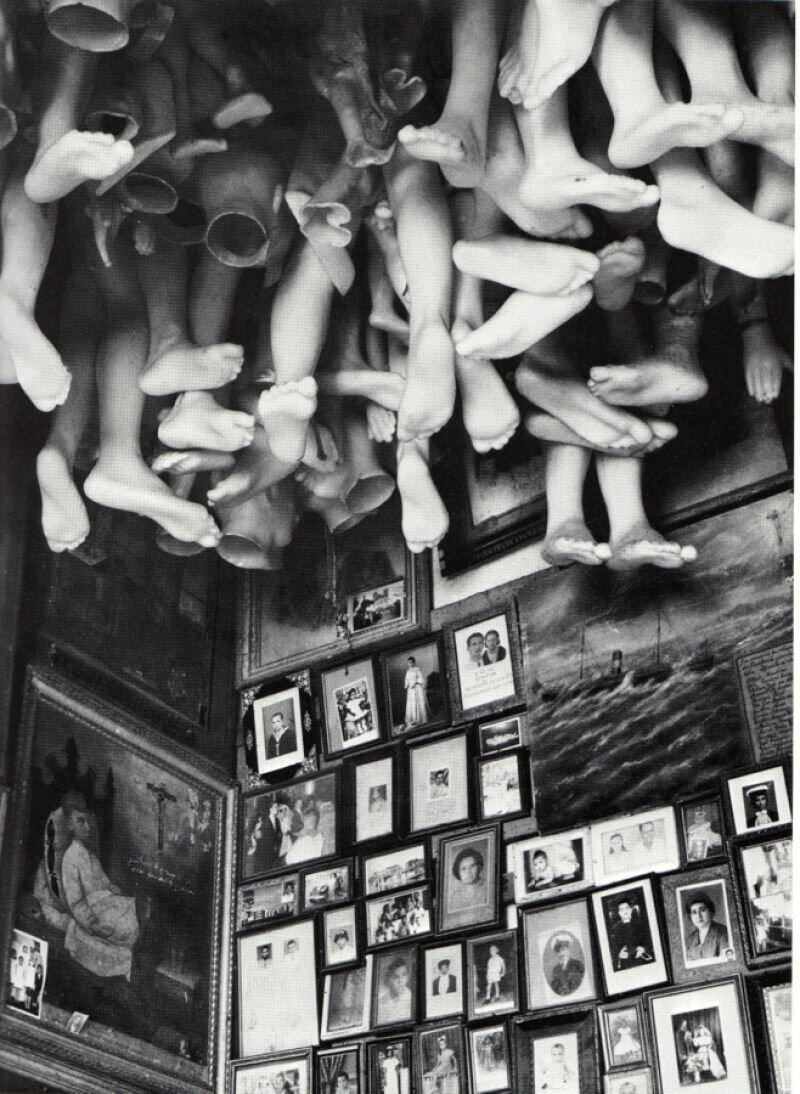

They look like relics from a superstition of a bygone past: arms, legs, hands and feet of wax raised high, hanging from the ceiling of a waiting room at a Brazilian hospital.In fact, they’re a good sign. They represent the tangible evidence of recovery since its only when a patient is successfully healed that his gratitude and respect is expressed by leaving the due saint an ex-voto (Latin for: from the vow made.) Doctor heal their patients by the grace of a saint or by that of the holy Maria: a relationship that no longer seems plausible to us, but is still very normal in Latin America and Southern Europe.

The ex-voto culture is as old as it is diverse. Calling on saints and gods for health and fertility is an ancient tradition. Like the pits found in the vicinity of Etruscan temples filled with votive offerings—feet, hands, breasts and eyes. This tradition is still upheld in Catholic countries, although the material and forms of the ex-votos have become more varied. The more simple ex-votos are made of silver plated copper, the more costly ones of solid silver. Some of the most attractive ones depicts the ailments or accidents they are devoted to curing or preventing. A man falling from the roof, a rider being catapulted out of his saddle, a woman being struck by lighting. But in the cloud (heaven) Maria, or a saint, watches over and ensures that all is well.

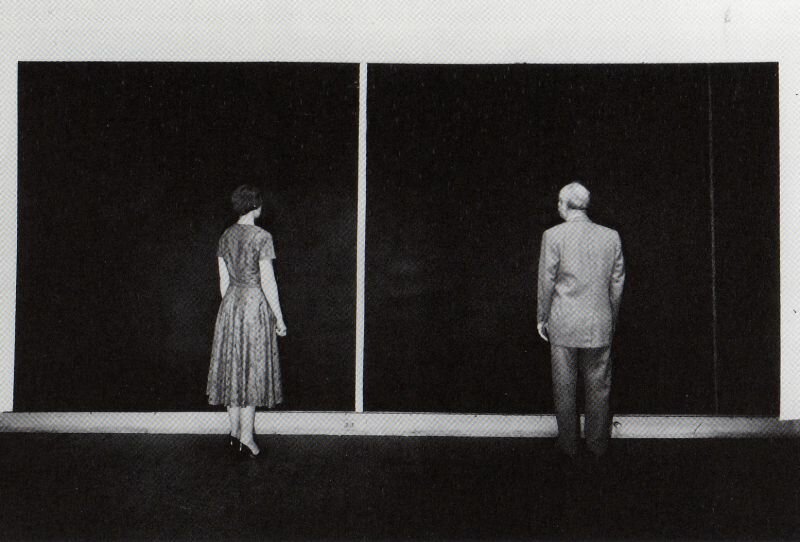

‘There was nothing, nothing at all to see.’ This line, which would become famous, was spoken by a visitor to a Barnett Newman exhibit on January 1950 in New York. Newman presented the monumental monochrome paintings, cut through by a vertical line, for which he would be well renowned later. Paintings without a title, without a motif. In a certain sense, Newman did not want to ‘show’, at least not to show any subject, no image referring to the history of fine art. That was the discovery he had made shortly before: he no longer needed a subject. He advised the viewer to look at his paintings from up close, and not from afar, which one tends to do because of their large sizes. ‘Paintings need to be felt, not to be read,’ was his adagio.

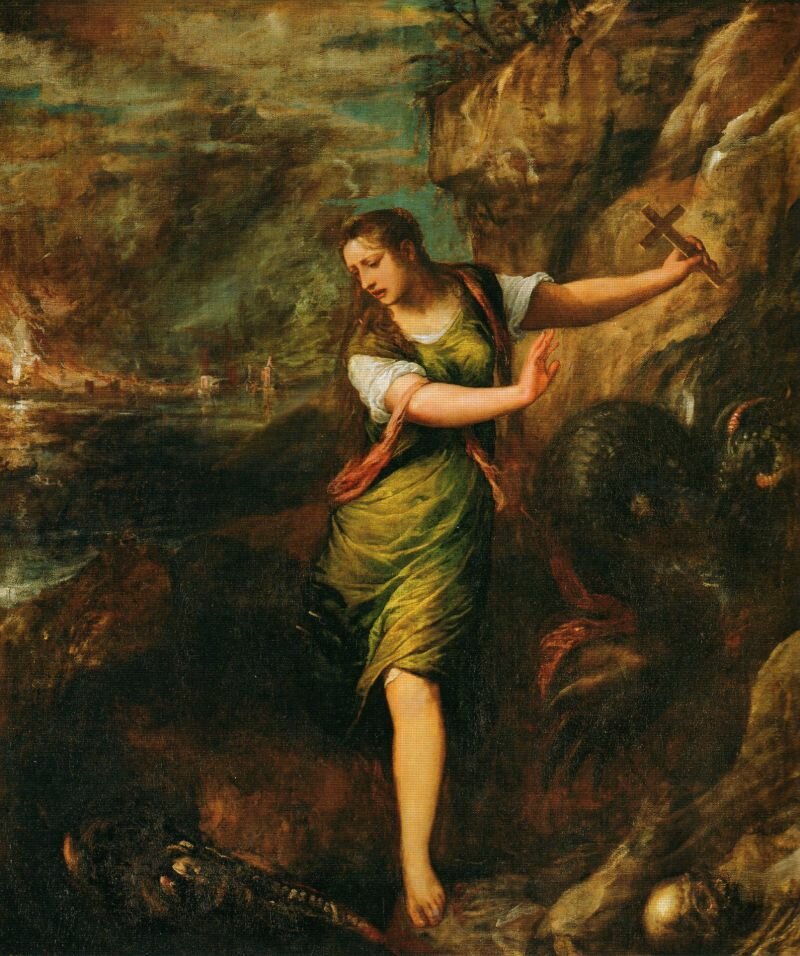

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Margaret_and_the_Dragon_%28Titian%29

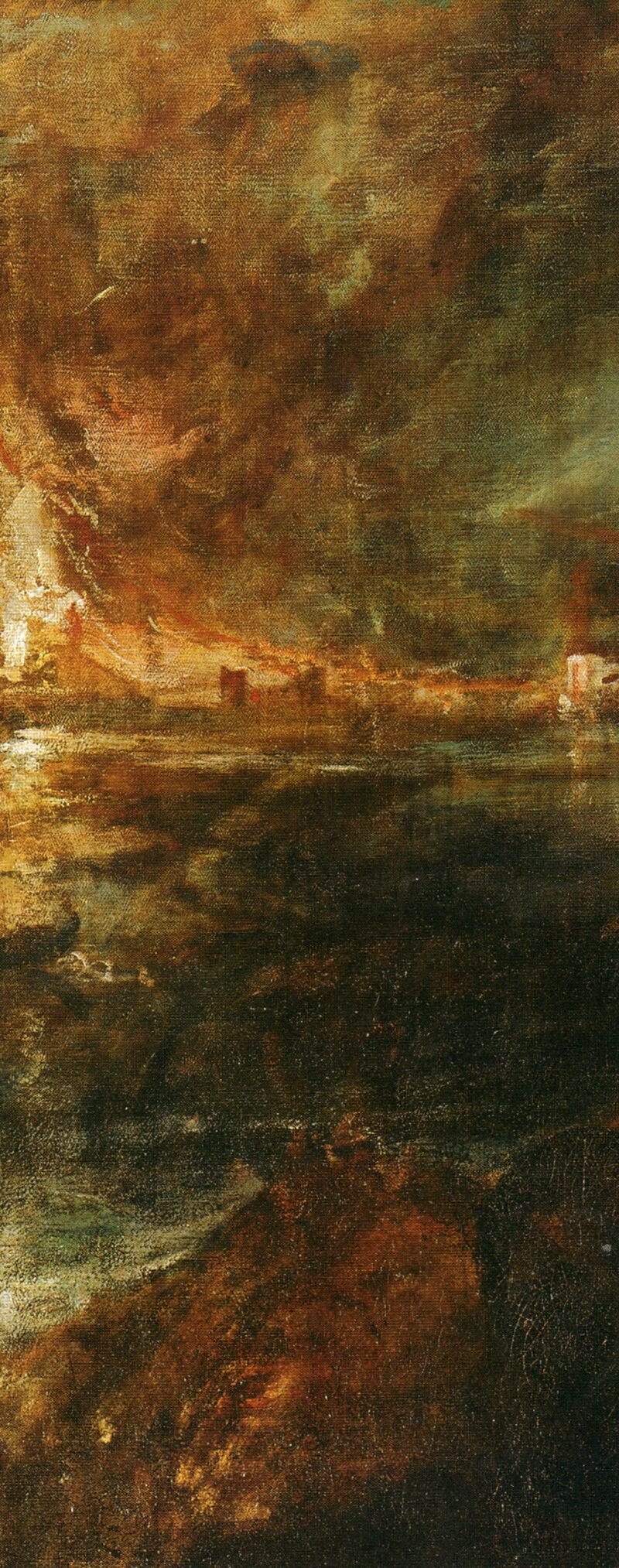

Four centuries before, around 1550, a similar discussion took place. The incentive was the paintings of Titian. At an older age, the master from Venice started to paint ‘invisible’ scenes. No longer did he bind colour to matter and shape, his palette had the figures dissolve in a kind of fog or haze. He built his composition with broad, bold brushstrokes and colour fields. Moreover, he left parts of the canvas unpainted, so that, as his contemporary Vasari put it, ‘one does not see much from up close, whereas from afar the paintings appear to be perfect.’ With ‘perfect’, Vasari meant that Titian’s paintings gave the impression of being alive.

The revolution that is born with Titian and comes to an end with Newman, is that of a category of painting that thrives on invisibility and shapelessness. It is an art of painting that shows the process of the métier, the dynamics of the brush, the use of colour, the texture. But most of all, it is a way of painting that involves the viewer in the work. For it is his position, his place, close to the painting’s skin or from a distance, that determines what can be seen. This form of painting creates the illusion of the viewer as a (co-)creator, an artist, who has to finish the work.

Ironically, this suggestion is raised most strongly by remaining at a distance from Newman’s work, yet by almost pressing one’s nose against the canvas in the case of Titian.

Detail, Titian, St Margaret and the Dragon, c.1559

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Margaret_and_the_Dragon_%28Titian%29

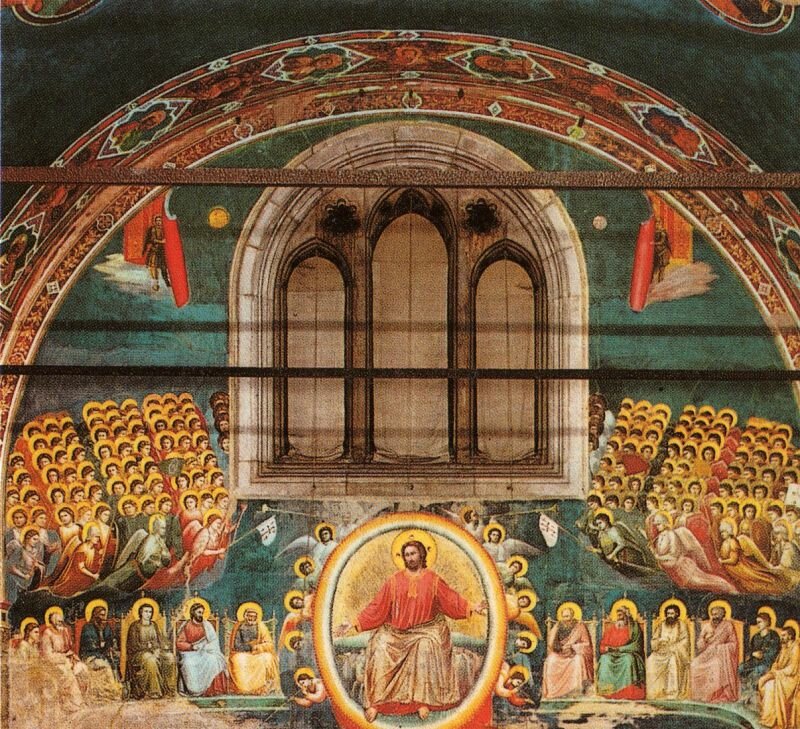

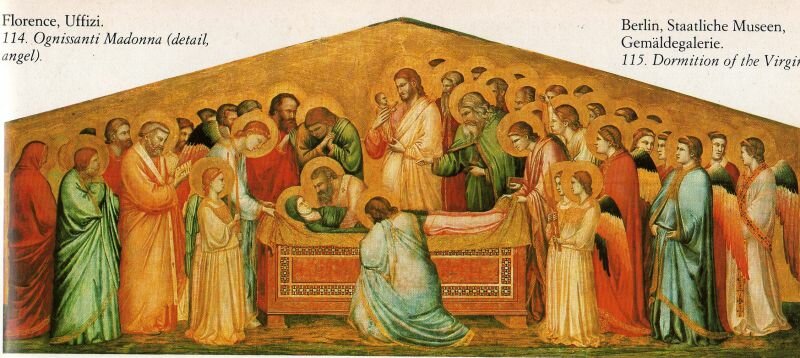

Giotto’s painting is praised for many different reasons. For its simplicity and realism, its clear narratives and compositions, its imaginative landscapes and architectures, its drama and use of colour. One of the Giotto’s most interesting innovations was his use of the isocephaly, or “levelled heads”: grouping figures on a horizontal plane, on level ground.

Giotto makes ingenious use of the isocephaly in his masterpiece, the murals at the Arena chapel of Padua.

In his monumental rendition of the Last Judgement, Giotto expands dimensions both horizontally and vertically. It’s plausible since the scene doesn’t take place on earth but in the kingdom of heaven. Moreover, he needed to find a solution for arranging the halos around the choirs of saints and angels.

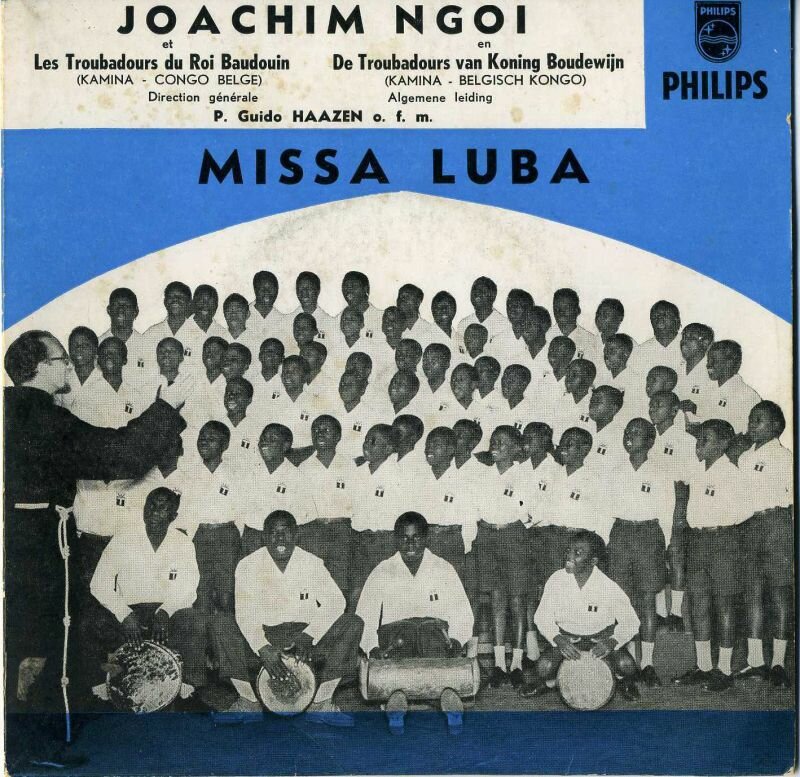

The Assumption of Mary in Berlin shows an interesting take on the isocephaly. The play between head and halo of partial overlap and complete visibility are taken to extremes.

Once fascinated by Giotto’s isocephaly, more and more details will start standing out. Like how within a large group, the exception sets the rule, by the individual figure looking backwards at someone standing behind him. Or the variation in how the crowns of heads arise above the halos in front of them. Or how subtle variations break the monotony of the group.

Giotto’s isocephaly is addictive. Gitto or Cimabue, painting or photography, football team or choir, you can’t stop looking. Once you’ve acquired an eye for it, the arrangement of the figures goes from being secondary to the most important aspect of his work.

Less is better, less is more. This principle has held the last century's art in a tight grip. Even now, the elimination of frills and the absence of the anecdote remain praised and encouraged by the majority of art critics and art tutors.

A lengthy history precedes the art of omission. Remarkably, the roots to this aesthetic approach lie in the Baroque; age of decorum, extravagance, excess, and the ornament. But this same seventeenth century period also gave way to a break in the tradition of following a narrative and by representing it scene after scene, like in a comic strip. The Baroque celebrates the climax and the apotheosis; that one instant in which an entire story is condensed into an ultimate moment of theatricality, frozen in time.

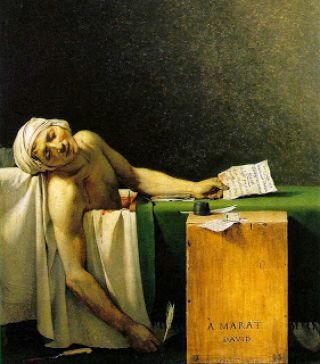

In 1793, the art of omission encountered a curious development in the form of the French painter Jacques-Louis David. His ‘Death of Marat’ is a world famous masterpiece, an icon of the French Revolution, an unequivocal image of devotion inspired by the events that instigated the uproar in Paris on July 13th, 1793 when a young woman of twenty-four named Charlotte Corday from Normandy murdered the Jacobin revolutionary leader, Marat. David’s idiosyncratic depiction of this scene might be considered religious and engaged rather than factual or pragmatic.

Jacques-Louis David

Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ inspired David’s brilliant depiction of Marat’s dangling arm. His ability to isolate this motif was genius. No painter before him had brought an arm to light in the same dramatic way.