Hundreds of cheap labourers are making money through websites like Amazon and Google Image Labeller. These Internet workers are also known as Mechanical Turks. Visual artists also make use of their services.

“What do you do for a living?”

“I’m a Mechanical Turk.”

It sounds absurd, but it actually makes completely sense. Worldwide there are millions of so-called MTurks active in dozens of countries: people with a computer and an Internet connection that, all the while clicking and tapping, make money. New international digital workers are added daily, even in Africa by mobile phone. Meanwhile, visual artists have discovered the benefits of this cheap labour: the first art projects using Mechanical Turks are starting to make their appearance on the Internet.

Organising labour over the Internet is an interesting affair. National borders are crossed with ease, and a social security number is unnecessary—all you need is a bank account. We’re already familiar with images of Asian youths gaming for hours on end for people in the rich West, but there are many other forms of online remote work.

The Mechanical Turk made its appearance in 2005 at Amazon and is based on the idea that we are all part of a great machine. Tasks can be found on the Internet for the reward of a few cents to several dollars. These are so-called HITs (Human intelligence Tasks) that vary in their degree of difficulty. You could, for example, insert tag words to photos and videos, arrange images by colour, write vacation reviews for websites or collect links about UFOs—that last example earns 15 dollar cent per link. Because the amounts are so trifling, Amazon’s Mechanical Turk site is also mockingly referred to as the “virtual sweatshop”. Still, many use the site to earn their whole month’s wages, while others earn themselves a bit of pocket money.

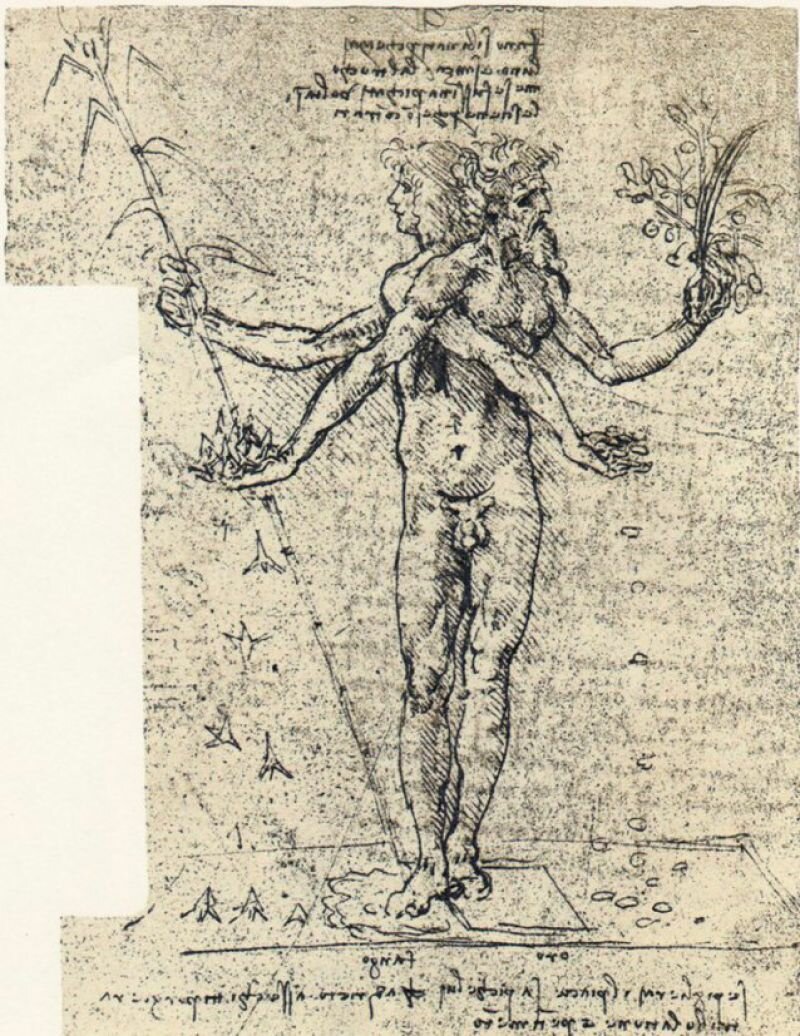

The term Mechanical Turk derives from a legendary chess computer from 1770, made by the Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen at the request of empress Maria Theresia. Old etchings show a doll wearing a turban, the Turk, who is sat behind a box onto which a chessboard is fixed. Viewers believed that the space underneath the board was empty, and that the doll was controlling the chessboard.In actuality, inside the box, a chess player was hiding. Through an elaborate system, he was able to see the chess pieces and move them using the doll’s arms. The apparatus, at that time a mechanical wonder, travelled through the royal courts as an exotic attraction. In 1836, Edgar Allen Poe attempted to describe the workings of the Turk, in order to show that there must have been a player of flesh and blood within the device. His essay, Maelzel’s Chess Player, is still regarded as the first “whodunit”: who was deceiving the audience, and how?

A reversal has occurred in our time: while people were first creating machines mainly to facilitate life, now machines need people to properly perform tasks. Good examples of this reversal are captchas, a type of small puzzle that can only be completed by a human being. Everyone who uses the Internet comes across a captcha sooner or later: for example, in the form of distorted letters or numbers that need to be entered when you take an action on Facebook. The computer knows that a person must have entered the correct interpretation of this information, because a machine is incapable of interpreting the distortion. This principle is used to ensure that replies to e-mail or blogs are not generate by machines; all to avoid nonsense, advertising, and other sorts of spam.

Filling in captchas can also be implemented differently. At this moment, thousands of books are being scanned into sites like Google Book Search. Things often go wrong during the scanning process, and letters accidentally become distorted. A machine cannot see or correct this, but we can. Every time you fill in a captcha, you could be helping a little by making a scanned and distorted text legible.

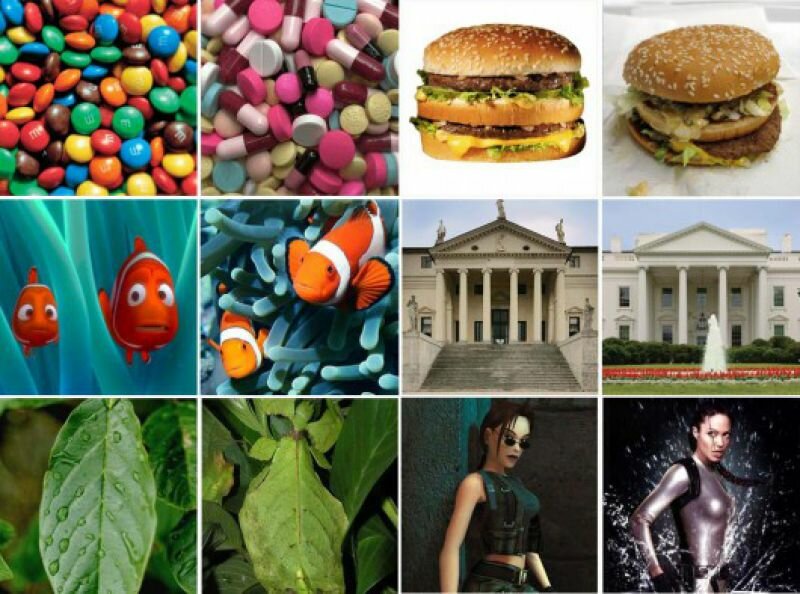

Another form of intelligently utilizing joint labour is Google Image Labeller, an online game where people supply images with “tags” (key words.) A player sees an image, for example, a red car in the forest. Through a database, he’s paired with an anonymous opponent. If you and your opponent fill in the same tags, you can go on to the next image. Thanks to many people adding tags to images in this way, we’re able to easily find images online.

You’ll stumble across the strangest forms of labour on the Internet. For example, the Internet project Payday (only for Americans) where you can earn 1000 dollars by hitching people with a credit card. Because you won’t want to be bothering your friends with this, you’ll go on a forum and offer 50 dollars for anyone who applies for a new card. This will then cost you ten times 50 dollars – meaning you’ve earned 500 dollars for yourself. Payday receives 1650 dollars from the credit card company for eleven new credit card holders, advertising money that used to be reserved for the “old” media.

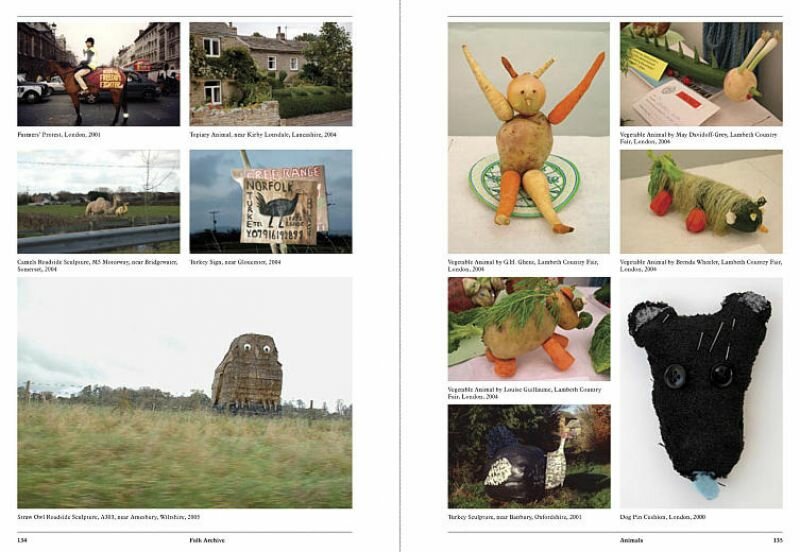

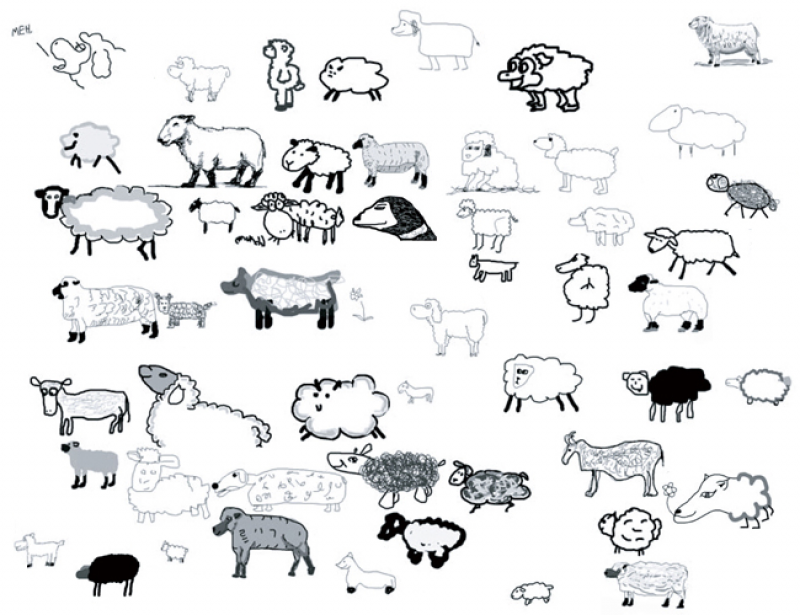

The American artist Aaron Koblin uses virtual labourers to make art. In 2006 he asked Mechanical Turks to make ten thousand hand drawn sheep. He offered 2 dollar cents per drawing, meaning the entire work cost him 200 dollars. He collected the sheep over a period of forty days; people completed the drawings on average in 105 seconds, which means that the wage comes down to about 0,69 dollar cents an hour. Koblin’s website shows a selection of these doodles that together form the work, The Sheep Market. Thousands of sheep stand against a white background, all of them facing to the left. Some sheep are accurately drawn, while others are drawn quite clumsily.

Koblin completed a similar artwork in collaboration with artist Takashi Kawashima, named Ten Thousand Cents. For this project, the artists divided a hundred dollar bill and asked the Mechanical Turks – who were unaware of what they were looking at – to draw a piece of the bill on a drawing application. The thousands of puzzle pieces can be seen online, pasted together into a new bill (on sale for $100). When you click on one of the pieces, you’ll see a film showing the example and how it’s been drawn. You can clearly see who’s done their best and who hasn’t: these pieces are inaccurate. Koblin’s most recent project with Mechanical Turks, Daisy Bell, has awarded him a prize for the media festival Transmediale in Berlin. The starting point for this artwork is the song Daisy Bell from 1892, which in the sixties was one of the first tracks to be recorded using synthetic voices. The song was also used in the final scene of the film 2001, A Space Odyssey, in which HAL the computer sings.

Koblin gave each individual Internet labourer the task to listen to a note, after which they had to emulate it (6 dollar cents per tone.) He then combined the tones to form a piece of music. When you view Daisy Bell online, you’ll see a graphical representation: a bar slides over the staff and you’ll hear 2088 voices that together, without knowing it, join in song and form an overwhelming cacophony. But however beautiful the result may be, Koblin says his wants his work is mainly an instrument to critique the use of the MTurks. They are usually required to perform simple and repetitive tasks. Their work is done on a contractual basis and the employers pay no taxes, and so laws concerning minimum wage and overtime are circumvented. In the case of Koblin’s sheep, the artwork is Koblin’s property and not the drawers, who renounced their copyright for 2 dollar cents a drawing.

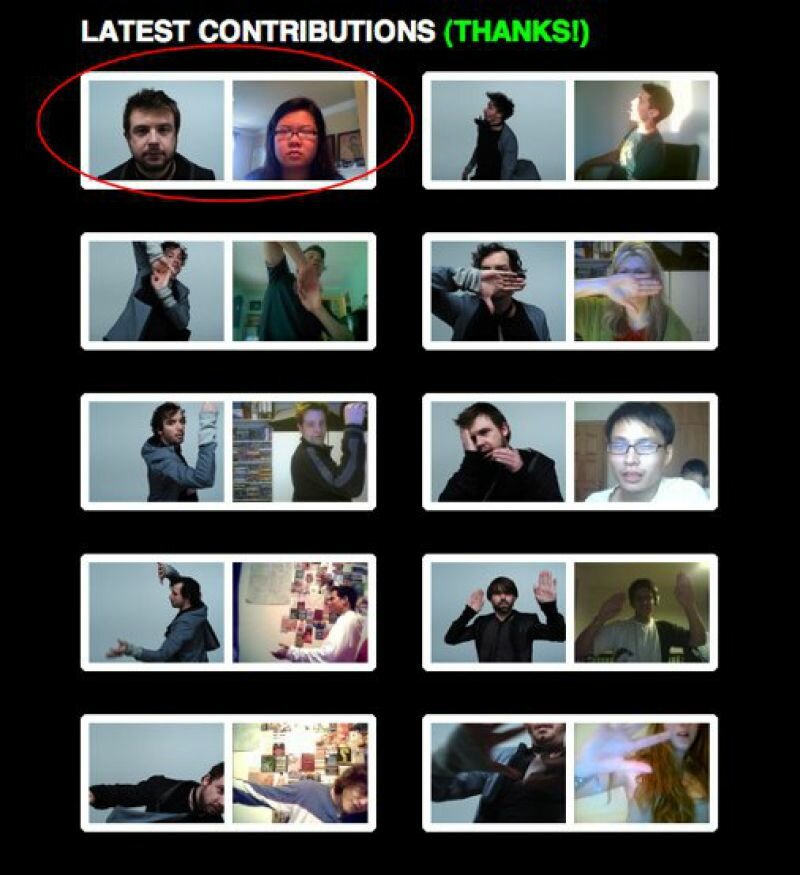

Inspired by Koblin, blogger Andy Baio wanted to find out who is behind the MTurks. He asked people to reveal their faces for fives cents. This fee was apparently too low—only two people reported themselves within 24 hours. After a bit of experimentation, it turned out that fifty-dollar cents was the minimum. The assignment was to make a photo portrait of yourself in front of the web cam holding a handwritten sign including the reason why you “turk”. “I turk for...” The result can be seen in a collage on his blog: thirty portraits of women and twenty men between 20 and 30 years old of diverse ethnicities. 21 turk for the money, 9 out of boredom or for fun.

In The Netherlands there are also artists who experiment with the Mechanical Turk. Artist John Puckey (29) and graphic designer Luna Maurer were asked to design Museum de Lakenhal’s annual report. They decided to ask the MTurks to translate the report into English, in spoken language. Most could not speak Dutch and recorded what they thought the text could possibly be about. On the website you can view the annual report and read the MTurks’ English interpretation. The experiment is funny and peculiar. An example of a sentence from the annual report: “This shift in thinking is not made by the grace of God,” interpreted by a voice with a South-American dialect: “The others in death, gave nothing to him by the grace of God.” Pucky has also worked on a video clip for C-Mon & Kypksi, a band from Utrecht, that makes use of Mechanical Turks. For the song More is Less, video artist Roel Wouters made a video in which fans can play along. The public is asked to imitate a pose that one of the band members takes in the video. One frame is selected from the video that you have to imitate to the best of your ability; upon which you take a picture of yourself and place it on the site. The website is very user-friendly. Thousands of people have taken the time to upload their image. The photos are, after a selection by MTurks, placed into the right sequence on the computer. Through this, a video is formed that shows a different person in each frame.Slowly, a video is growing where the musicians see themselves mirrored by their fans. In total there are 14000 available frames. The photos rotate, the video refreshes itself, and so everyone has their own “frame of fame,” which is also the name of the project. The hired Mechanical Turks are the ones who evaluate whether people have taken the right pose and if the image quality is good enough.

The influence of virtual labour is still young, but the development has already had unforeseen consequences. Who had ever thought that Mechanical Turks would be used to track missing persons? In 2007, friends of the American millionaire Steve Fosset came up with the idea to, through Google Earth, employ MTurks to assess satellite photos of Nevada. They hoped that someone would spot wreckage pieces of his disappeared airplane. When computer scientist Jim Gray and his sailboat went missing, MTurks were also employed. The workers were given around 25 cents to study a series of satellite photos. Aaron Koblin makes use of the “power of numbers” with art works like The Sheep Market or the music piece Daisy Bell. With the music video One-frame-of-fame, the outcome is less predictable. When the project started, they were unsure what would happen. Last Monday, the 25th, 10217 participated. For the makers, the popularity and creative interpretation came as a surprise. The potential for art lies within this unpredictability, whether made by MTurks, fans, or gamers.