Hito Steyerl, a German artist and theorist, wrote an article in 2009 called ‘In defence of the poor image’. Poor images are the heavily compressed images that are available for everybody online. They are either the poor copy of a better, more professional original, or an image that was made by an amateur and was poor to begin with.

In the six years since then, the image quality of the average video on Youtube has gone up dramatically and so have the average consumer cameras, but there is still a difference between professionally produced commercial films seen in cinemas and the ones available online. How long this will remain the case is the question. But for now I think Seyerl’s argument remains interesting. I quote:

“Poor images [are] popular images—images that can be made and seen by the many. They express all the contradictions of the contemporary crowd: its opportunism, narcissism, desire for autonomy and creation, its inability to focus or make up its mind, its constant readiness for transgression and simultaneous submission. Altogether, poor images present a snapshot of the affective condition of the crowd, its neurosis, paranoia, and fear, as well as its craving for intensity, fun, and distraction.”

You see these contradictions of the contemporary crowd continuing in today’s visual aesthetics. And in these aesthetics there is of course space for critique and experiment. Where again I would like to stress that experiment isn’t necessarily critical.

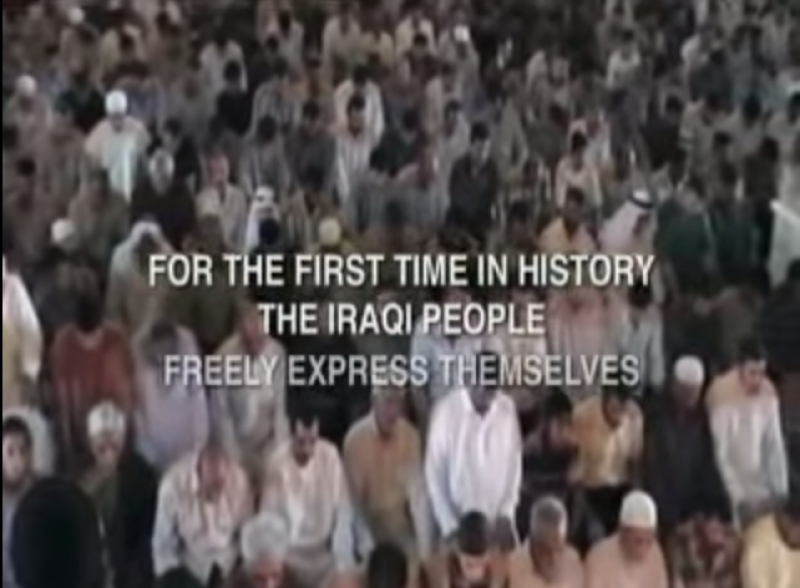

In 2004 a film was made called ‘the voices of Iraq’ in which US filmmakers gave 100 camera’s to Iraqi people, just after the fall of Saddam Hussein. Although the idea is given that many different viewpoints are voiced in this film, I would argue that this film is pure US propaganda. The democratisation of the camera is here symbolising the democracy that the US brought to Iraq, finally allowing people to speak freely.

Steyerl speaks of this tendency of the resistance becoming part of the value system of capitalism. She uses the example of conceptual art, first resisting the fetish value of the object, which had become so valuable in the art world. But then, as value was dematerializing within capitalism on a larger scale, conceptual art fitted in perfectly and fetish value could be assigned to dematerial concepts just as well as to material objects. The same goes for the poor image:

“On the one hand, [the poor image] operates against the fetish value of high resolution. On the other hand, this is precisely why it also ends up being perfectly integrated into an information capitalism thriving on compressed attention spans, on impression rather than immersion, on intensity rather than contemplation, on previews rather than screenings.”

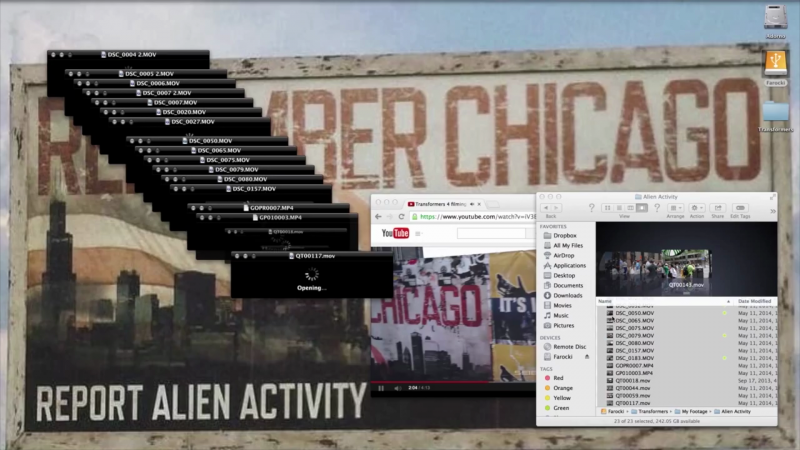

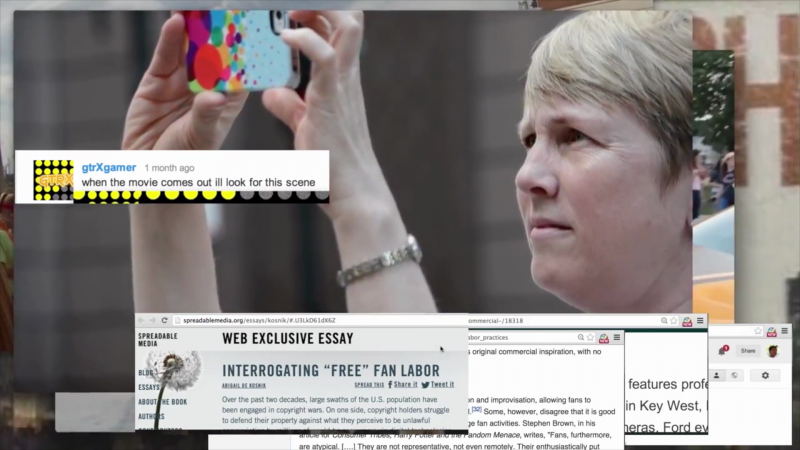

In the film ‘Transformers, The Premake’ we don’t only see the multiplication of the body and the multiplication of the camera, but also the multiplication of the screen. We see how the plurality of images produced by amateurs during the shoot of the film the Transformers, can be used as a source for promotion, or as a way to emotionally bind your audience. Crowd filming, just like crowd funding and crowd sourcing. The production potential of all these individuals together is enormous and is therefore exploited by commercial and political parties. (Transformers, The Premake)

Wark McKenzie speaks of Hito Steyerls writings in a very recent article. He says “The labour of spectating in today’s museums is always incomplete. No one viewer ever sees all the moving images. Only a multiplicity of spectators could ever have seen the hours and hours of programming, and they never see the same parts of it.”

Of course the same goes for all moving image online. Maybe here not even the multiplicity of spectators have ever seen the whole. This abundance of images also causes a kind of invisibility. There’s a good chance to get lost in this overload of images, or to just become a piece of data in the data pool.

The last fragment I will show is an excerpt of Steyerl’s video ‘How not to be seen, a fucking didactic education mov file’. It’s a tutorial on how not to be seen in a world where we are always being looked at. We are constantly filmed by drones, surveillance cameras, our own smartphones and those of others. We never know if someone might have hacked the camera or microphone on our laptop. Our location can always be tracked though our smart devices. We can’t escape being seen if we want to take part in society. At the same time we have become tiny particles in the large pool of images. Our physical bodies don’t matter so much anymore; it’s the data that we generate that counts. So in a way we have become invisible. Paradoxically Steyerl’s video on how not to be seen, is at the same time a tutorial to escape invisibility. (How not to be seen)