I tried diligently to keep a straight face as I looked at the plate of sausages and strawberries in front of me. One of the sausages had cracked open, causing its dubious contents to ooze out right onto the fresh strawberry underneath it. The whole sad scene was covered in a filthy grey blanket of thick smoke and I wish I had dared to take a picture then and there for memory’s sake. The smoke was coming from the cigarette weged between the scrawny fingers of the woman next to me. She topped it off by harshly coughing all over the sausages, then said in all sincerity: ‘Why don’t you take a sausage, girl?’ ‘No thanks,’ I said, meanwhile heavily reconsidering my recent career decision.

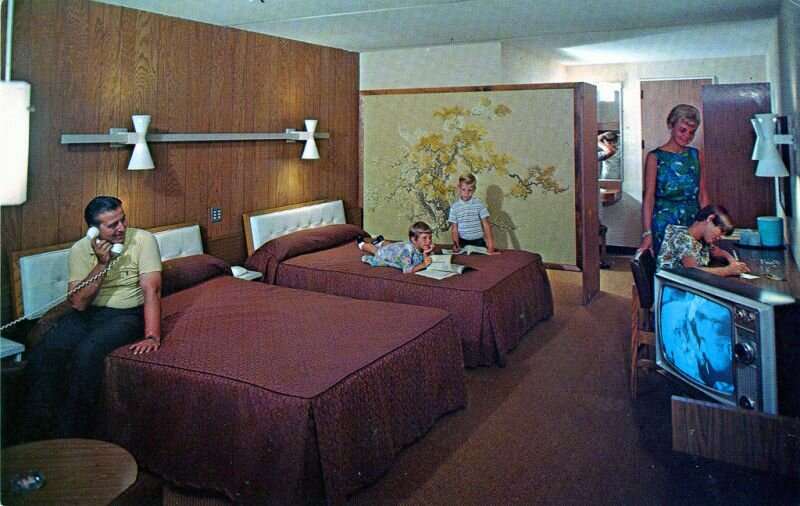

Until recently, I had worked in an office where I enjoyed the company of my co-workers immensely and had thought optimistically that at each working place, there were top-notch people, in whom I would always be able to find inspiration for better days. I would continue working at this new place and keep my newly found gems with care. I would furthermore elaborate on these opportunities in texts, projects and future plans to-be-determined. Aside from indulging in this endearing optimism, I subjected myself to an experiment. How far could I go in selling my soul when it came to side jobs while managing to regularly do artistically legitimate things? When would I be an artist working in a hotel on the side, and at what point was I working in that same hotel with merely an artistically inclined hobby? Where is the balance and how far could I go?

Meanwhile, I was well underway indeed, and I felt the black void eyeing me. ‘Oh dear”, I thought, while rethinking my motives to work in this hotel. The cigarette had by then gone out, and the sausages and strawberries had been eagerly devoured by my company at the table. I scrutinised them one by one and considered their potential as part of my next project (or perhaps Sunday art session). The lady next to me was a fine specimen at any rate, and likewise the other ladies at the table wouldn’t be out of place in my collection of remarkable colleagues.

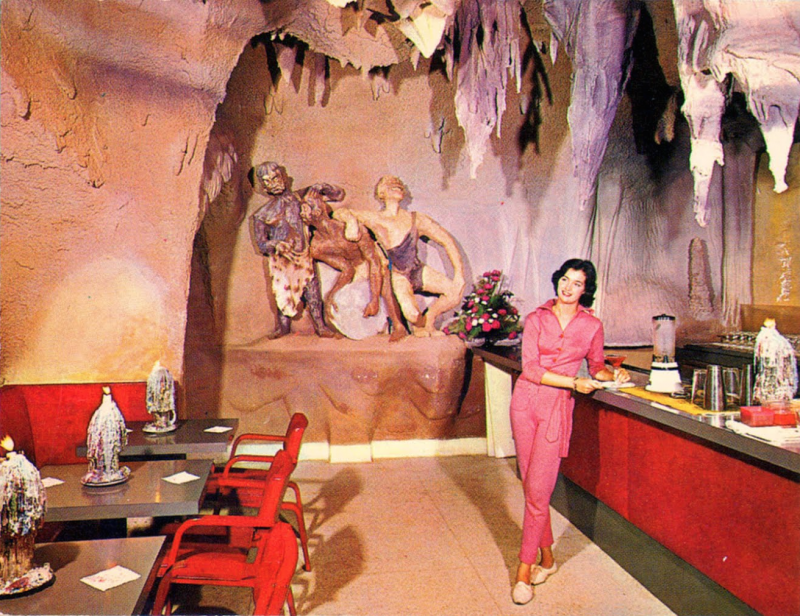

Rita, for one, had tobacco-coloured hair, ditto trousers, and chewed her sandwich in silence; Belinda entrusted me with hotel secrets, such as that it is endlessly preferable to not clean the rooms of cyclists or the Chinese; Denise told me proudly that she had left her junkie past behind her and had worked a solid thirty years for the hotel. She smiled baring her few remaining teeth and I smiled back. I was glad for her, but I’m always slightly creeped out when people at very unpleasant working places tell me that they’ve been working there for a very long time. I break out in sweat as I see my life flash before me, seeing the my future self as that person who, after art school, has begun ‘temporary’ employment, only to get stuck in it forever. People at an academy reunion will say something along the lines of: ‘Have you heard the news on Gerda? Been working in a hotel for thirty years.’ ‘The Volkshotel?’ ‘No, just some hotel. One of those along the highway whose name nobody really knows.’ ‘Oh.’

The roar of the radiators next to the room where we have our break saved me from the nightmare. My colleagues had stood up to get back to work and I considered for a moment to run off and never come back. I would like to emphasise, though, that I have no problem whatsoever with cleaning and similar jobs, as long as I manage to get some satisfaction from it. I have cleaned the houses of elderly people with great love, I have worked serving breakfast in hospitals, I’ve delivered mail for an entire summer (in my rain suit) and I have been personally responsible for planting roughly a thousand little plants in excruciatingly small pots on an assembly line. After this series of quite specific trades, I could go all out in my year long period as a teacher at an art centre, I worked in a fantastic shop (which has unfortunately closed), and, via the office, finally reached the hotel. The plan was to work there just enough to be able to pay my rent, and to otherwise get a good look at all the colourful visitors and their rooms in the name of art, and to then profit from it. As you will have surmised by now, my disappointment was considerable.

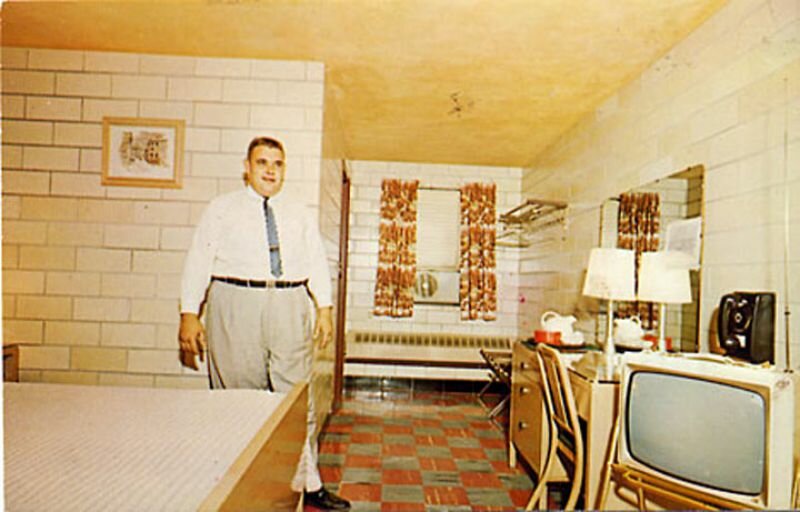

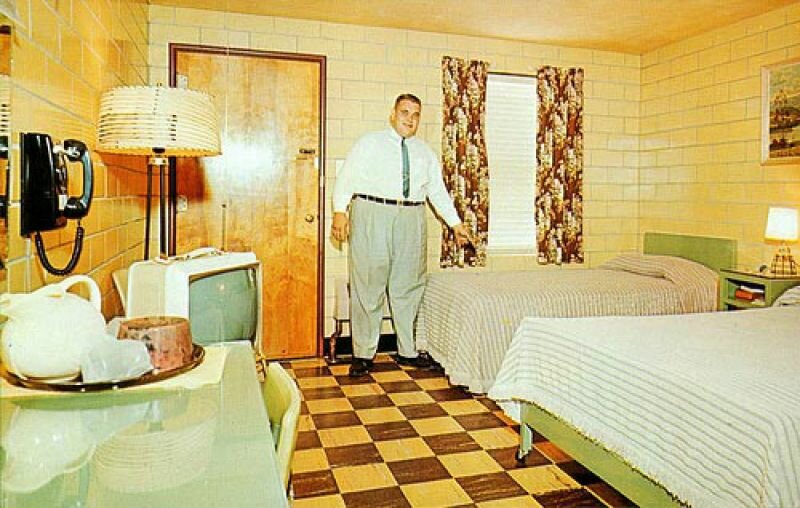

It was a characterless hotel where my job description consisted of getting the rooms to look as clean as possible. Until recently, I had enjoyed being in hotels, but those days were behind me for good. I pulled hair that belonged to strangers from shower drains and was instructed to dry toilets with towels (really) as well as to clean used cups by rinsing them with cold water before putting them back on the shelf (really). Not only was my Theory of Employment of before severely threatened, but I also began to worry about my karma as I carried out orders that turned the hotel into one big death trap of bacteria, diseases and other disgusting pests. Therefore, I decided to throw in the (filthy) towel and to look for a different side job. The risk seemed just too big to stay and find out where I would end up then.

From the one strange working environment I rolled straight into the other, where I planned truck routes throughout the whole country from a kind of control centre. As far as art school graduates go, I am pretty good at focussing, coordinating and organising things so it seemed no harder to do the same thing applied to truck drivers. I worked hard and eventually bit myself in the butt by planning everything so efficiently that I had finished the job three weeks before the intended date. But maybe that was for the best, since my colleagues knew that I was employed on a temporary basis and decided for the sake of convenience to act as if I had already left. It was a strange experience that I wouldn’t wish upon anybody.

Meanwhile, my projects grew like cabbage and I was asked for the most splendid things. I participated in a documentary on creativity, founded a meeting place that drew a lot of visitors, interviewed artists and was told by everyone that I was doing so well for myself. It was true that during my free days I worked passionately on my projects and saw them grow, but it was still bothering me that I could not earn a living with what I did best. In this way, I dug for both dream jobs within the cultural sphere as sad job offers within the other one.

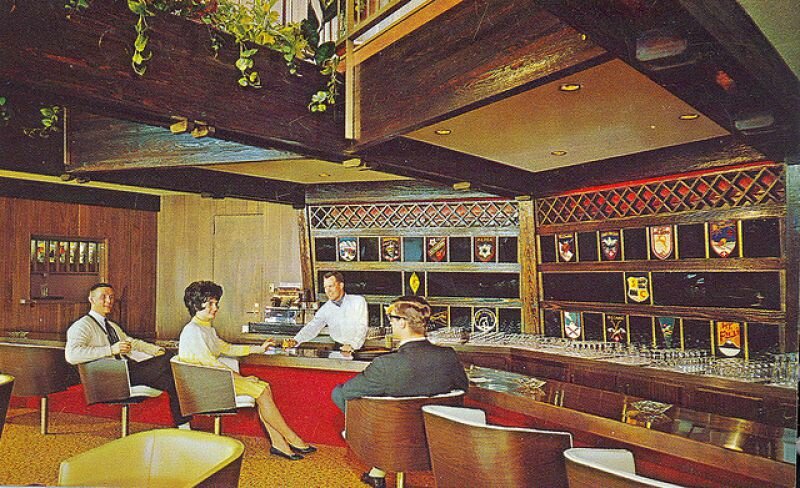

Hooked on the employment version of Russian roulette, I kept on playing. Was it going to be another miserable side job or would it be something else? The gods proved benevolent in my favour, for instead of the next grey work spot, I was granted the chance to tag along with the editors of the magazine Kunstbeeld. Not only did I discover that my heroes behind Kunstbeeld were very sociable, but also that there is paid work in this world that challenges your talents. I immersed myself in it completely; I emailed back and forth with artists and their assistants, interviewed Marlene Dumas while I was quivering like a leaf, and travelled the entire country in the name of art. I wrote my reports passionately, took in every possible experience and prepared for what would come next.

I hoped with all my heart and soul that I could do something in which I could work with both my brains and my pen, where I could coordinate and work together with people that make me happy, and so that, like the cherry on the cake, I could earn the roof above my head. After being rejected by email at least every day, all of a sudden there was the message on Saturday night that said: ‘What line of work are in you nowadays? Are you good at organising?’ I looked at my screen and up again, thinking for a second that the universe was surely playing a cruel game with me. ‘I am very good at organising.’ I replied. After many messages back and forth and one conversation, I have suddenly been equipped with a real job with all kinds of things I like and am good at; I work for two very nice people, who even invited me along to Cape Town to do even more wonderful things.

Trying to comprehend this turn of the plot, I think back to last year. The office, the trucks, Kunstbeeld and even the sausages and strawberries on a plate in that hotel. I remember the smoke blowing over them and realise I have escaped a certain destiny. A smile curls slowly upwards on my face. For now.