Born in Suriname and raised in The Netherlands, Haarnack maintains his collection on the sixth floor of a sleek apartment block in the eastern part of the city, overlooking the area that was once the docklands of this city.

It was here that Nahuel Blaton, my fellow Anthropologist in Art, and I were first exposed to the musty scent of thousands of rare books, common publications and mass-produced postcards; a silent lapidarium of all topics Surinamese.

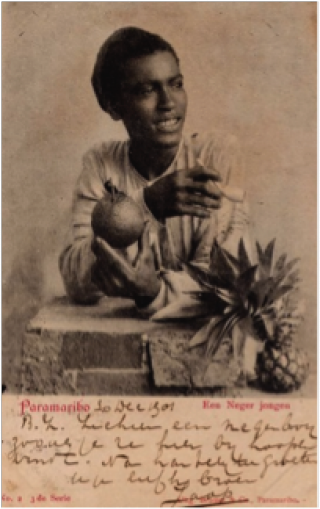

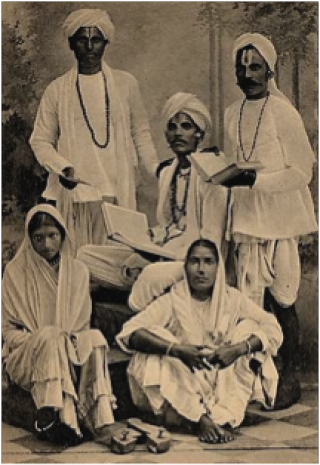

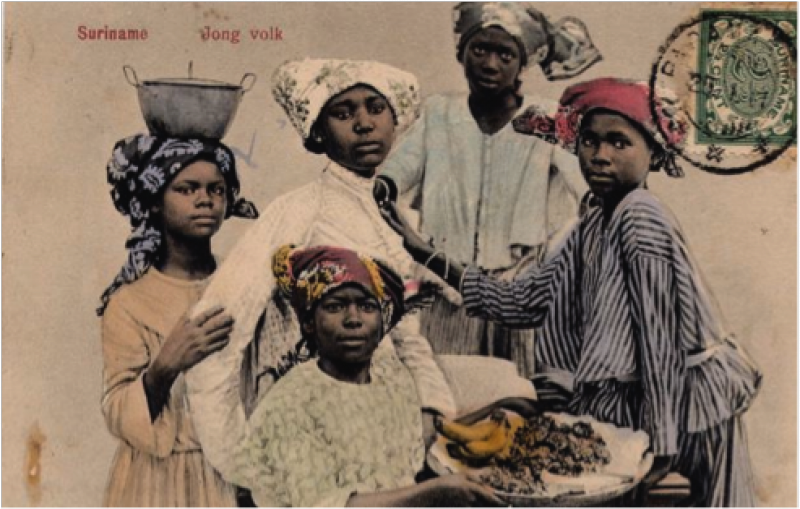

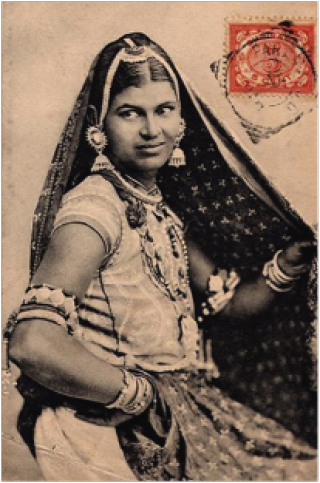

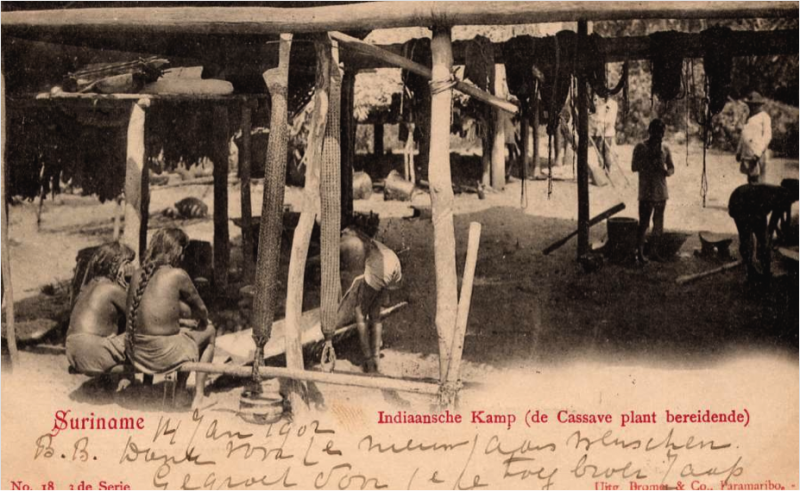

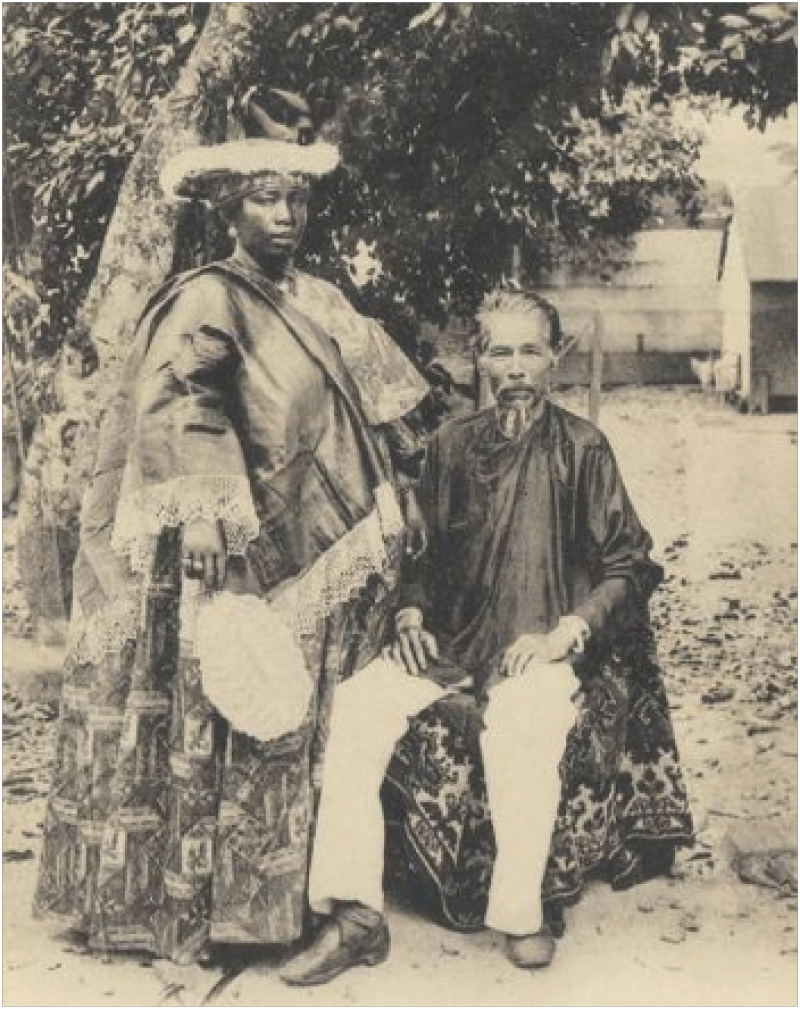

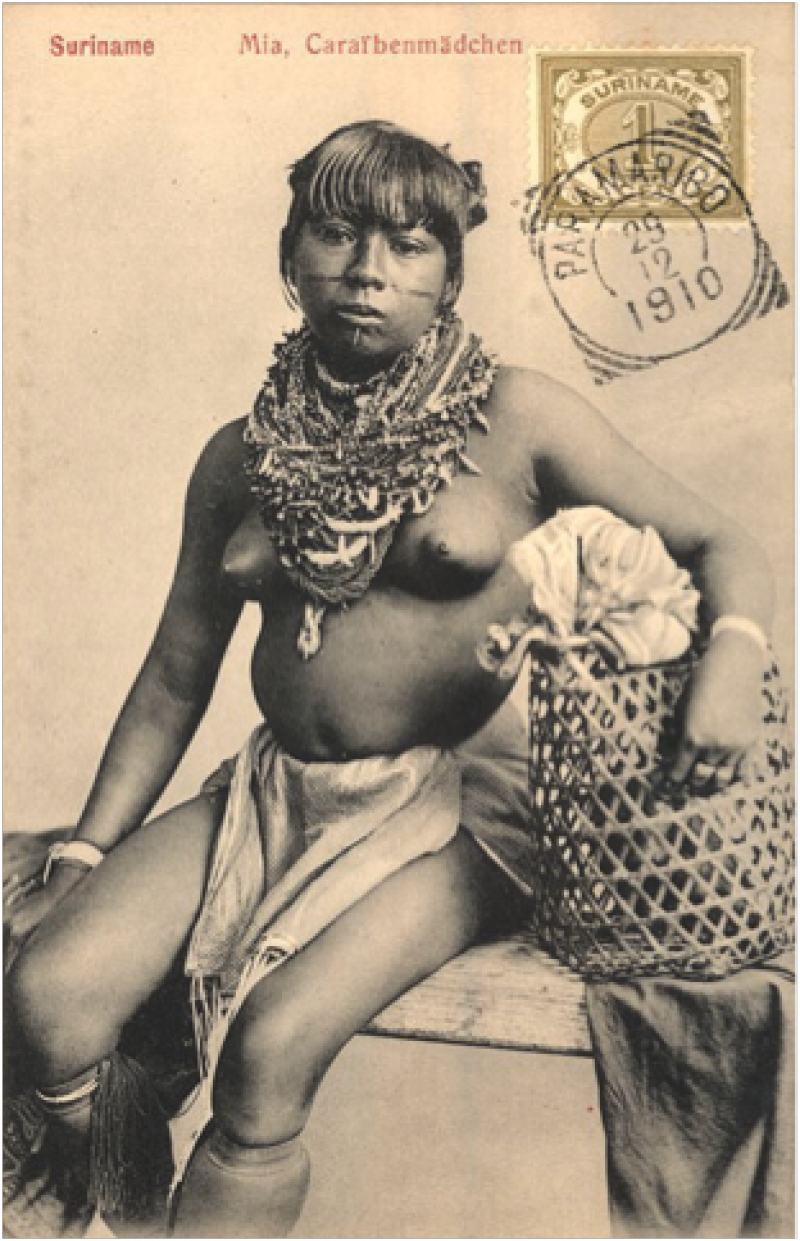

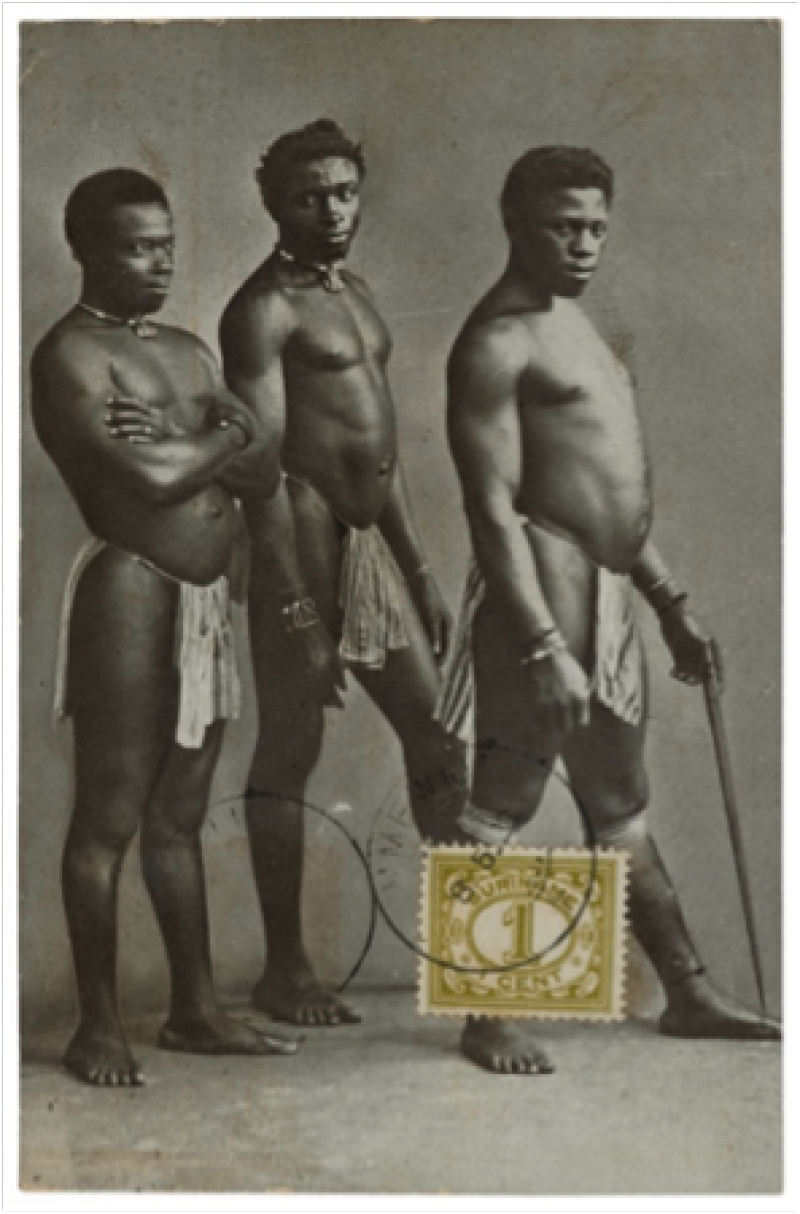

However, when Nahuel Blaton and I first visited Haarnack’s bibliophile’s wet dream, it was the fantastic collection of postcards that caught our eye and inspired the direction of our common exhibition. We flipped through a broad spectrum of photographed subjects; plantation mansions, infrastructure, buildings in Paramaribo, cityscapes, Paramaribo’s harbour, churches, seemingly casual street-scenes as well as exotic fruits and agricultural products. The subjects that particularly made an impression on us however were those of people. More often than not, neatly categorised into ethnic and social groups; one came across various tribes of Amerindians (‘Indianen’ in Dutch), Bushland Creoles (then known as ‘Bosne(e)gers’), City Creoles (‘Stadscre(o)olen’), Indians (known as ‘Britsche Indiërs’, ‘Hindo(e)stanen’ or the rather more politically incorrect term of ‘Koelies’), Javanese and Chinese.

Many of the postcards are attributed to and undersigned by one Eugen Klein. Born in Mannheim in 1869, Klein moved to Suriname in the 1890’s to set up a professional photography studio in Paramaribo. For some 30 years, up until his death in 1927 in Paramaribo, he was the most prolific photographer of all things Surinamese with perhaps his most productive period between 1900 and 1905. After 1927, his widow Louisa Schrader and her children continued running the photographic studio on the Domineestraat C35, at the corner of Vaillants square in Paramaribo, up until the Second World War.

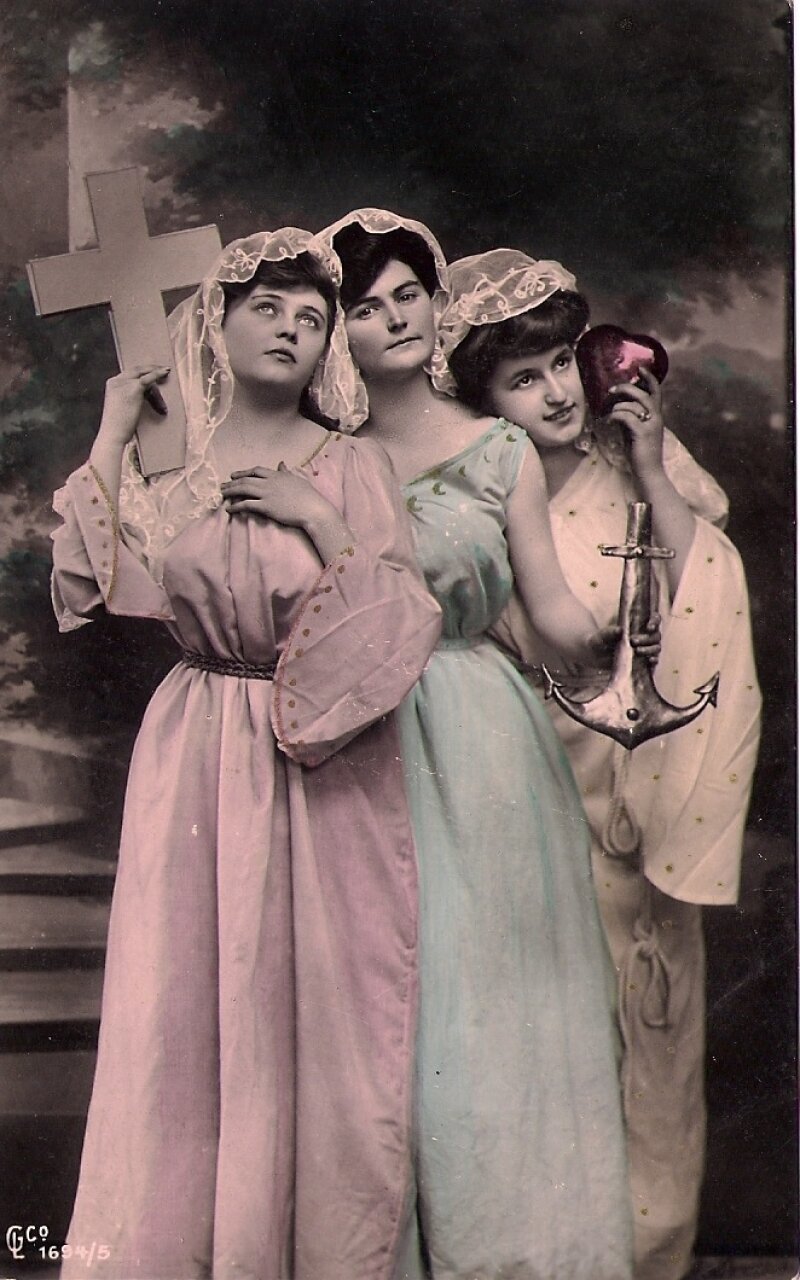

Some of his photographs were commissioned by the primary Evangelical Missionary Society in Suriname; the so-called Hernhutter Mission, named after its first colony, Herrnhut (“unter des Herrn Hut – under the protection of the Lord), located in Saxony, Germany. The Hernhutters had a paradoxical role in the development of Surinamese society. On the one hand, they carried out a doubtlessly benevolent plan of socio-economic advance in the impenetrable interior of Suriname by providing a programme championing education and literacy.

On the other, they were also instrumental in the behavioural ‘pacification’ of Suriname’s ‘heathen’ population. This, in the typically religious vein of the period, was coupled with an emphasis on the fight against ‘immoral’ co-habitation, an emphasis on work ethic and a sedentary way of life. Their main business, of course, was that of religious conversion within the various groups of Bushland Creoles and Amerindians. It seems likely that the Hernhutter Mission in Suriname commissioned Klein as part of a political agenda to convince the colonial authorities, as well as benefactors back in Europe, of the success and necessity of their presence.

Sifting through literally hundreds of these single or group portraits we realised that what we were looking at was the fragmented imagery of a people before they were to become the nation they are today.

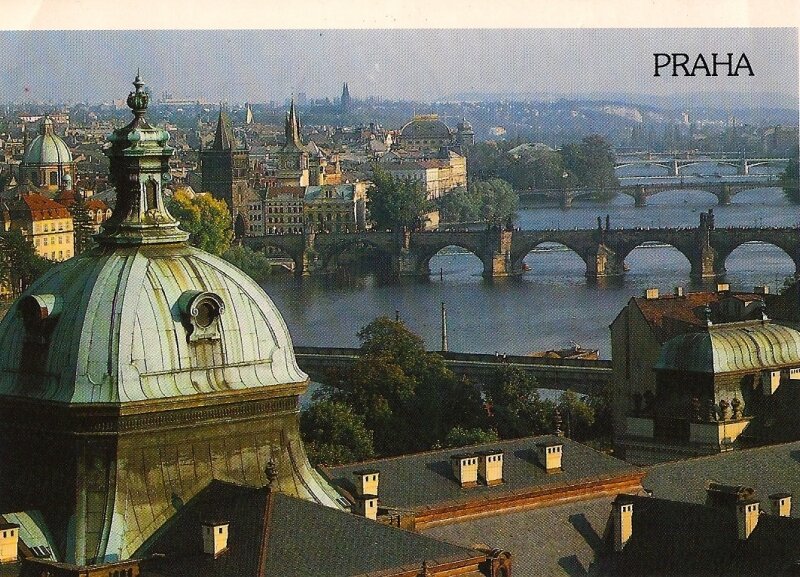

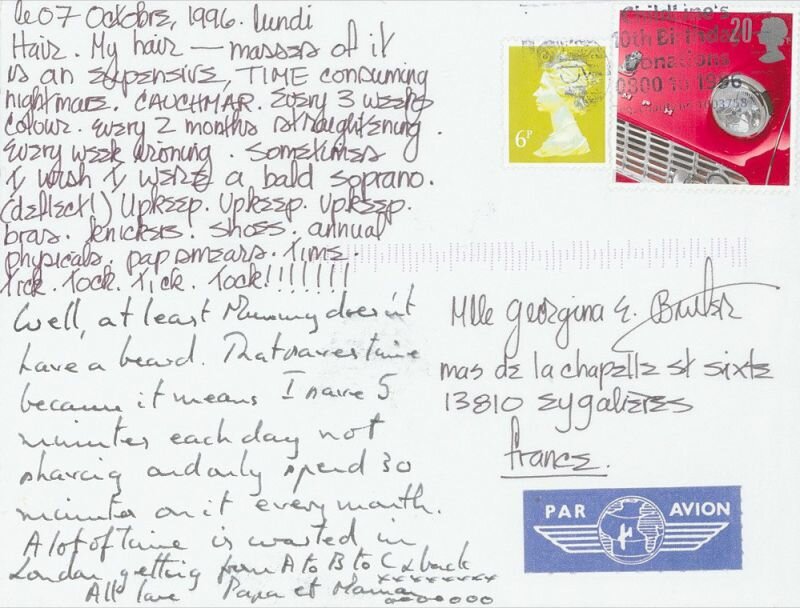

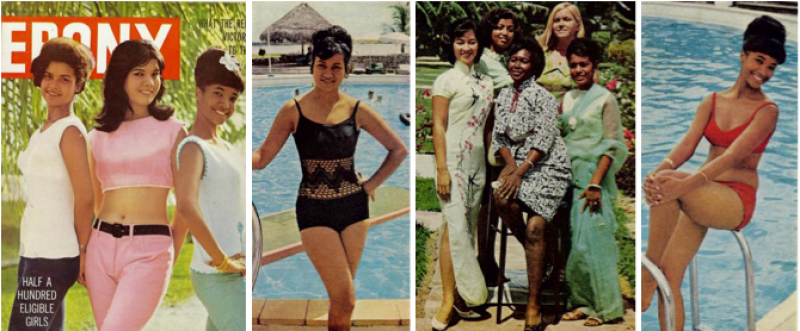

With the introduction of the photographic film in 1871, taking pictures became a relatively easy praxis, even in the tropical climate of this Dutch colonial possession. Coupled with the intensification of economic and political interests that led to an ever-higher frequency of Europeans visiting, working and living in the colony, this would ultimately lead to a veritable boom in the postcard industry. Family and friends back in Europe could now receive visual documents of the exotic far-away where their senders resided and worked. Mass-produced and –circulated, these cardboard-mounted images were intended for consumption by a white, urban bourgeoisie back in the Motherland.

No subject was more popular than that of the exoticised and eroticised peoples that inhabited the distant crown dominions. These, incidentally, are at the same time the most ethically problematic of subjects. For in the practice of photographing these people, one inevitably stumbles across a kind of subjugation, exemplified by both the poses of the subjects, as well as the redundancy of the captions that inscribe them.

“Four generations of Indian women”, “Chinese man with his Creole wife”, “Coolie in Paramaribo”, “Group of Bush Negroes”, “Creole Beauty”, All individuality is negated in these captioned postcards and all individuals are relegated to remain mere examples of their respective ethnic categories.

The backdrops, often with hints of lush verdant foliage, seem to imply an original environment of virgin purity and, implicitly, the primitivism of the ethnic subjects. The artefacts that they wear and grasp – including calabashes, bows, arrows and feathers – are of such formulaic appeal that one would be surprised indeed if these were not staged by the photographer.

The strength of these postcards may lie in the sense of estrangement that his portraits evoke. A sense of estrangement that lies somewhere in between the distinct past that the images evoke, with the paradoxical realisation, that this distant past is, in fact, uncomfortably near. These visual documents of bewildering clarity and from a not-so-distant past attest to the photographic praxis of production, circulation and consumption that rendered huge segments of the global population into mere objectified ethnographic exhibits.

So, let us be thankful that amongst us, there exist those individuals and institutions that are dedicated to the preservation of material from former colonies, different mores and bygone times. I invite all to subscribe to Buku’s blog on books and other ecclectica. Mr Haarnack’s enthusiasm for all matter Surinamese and published will prove to be as infectious as it is to us, Anthropologists in Art.

Visit: www.buku.nl