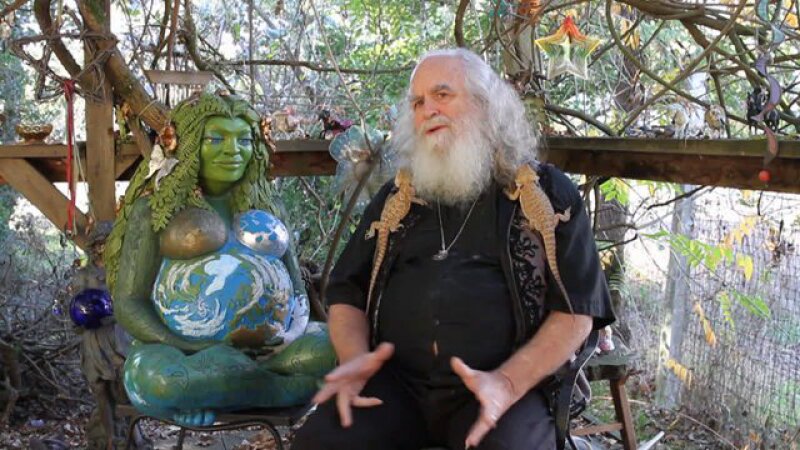

A series of fragments from the multichannel video installation 'The Experts' that is part of the Damagomi Project by Floris Schönfeld. The work consists of a number of interviews with a group of experts on the subject of the possibility of a post-anthropocentric relationship with the natural world. The experts are; Pit River shaman Floyd Buckskin, audio ecologist Bernie Krause, biologist Rupert Sheldrake, anthropologist Ida Nicolaisen, philosopher Jacob Needleman, wizard and paganist Oberon Zell-Ravenheart and sociologist Fred Turner.

In March 2014 I met Rupert Sheldrake at his home in Hampstead, London. I had been trying to meet him for about a year and had written him a number of long and increasingly pressing emails. He finally granted me a 20 minute interview, more to get rid of me than anything else I was presuming. That morning, in his pleasantly eclectic study, he summarised his basic position on the role of science, consciousness, religion in relation to his own personal belief system. The overarching view which permeates his work is a particular variation of the idea of panpsychism. This is by no means a new idea, but it seems to have once more gained relevance as the once ‘simple’ problem of consciousness has proved deceptively difficult to explain within mechanistic science. In his book A New Science of Life (1981) Rupert Sheldrake proposes the theory of morphic resonance in which he explores the idea of a universal, extra-human sentience that is present in all living things. His theory states that "memory is inherent in nature" and that "natural systems, such as termite colonies, or pigeons, or orchid plants, or insulin molecules, or galaxies, inherit a collective memory from all previous things of their kind.”

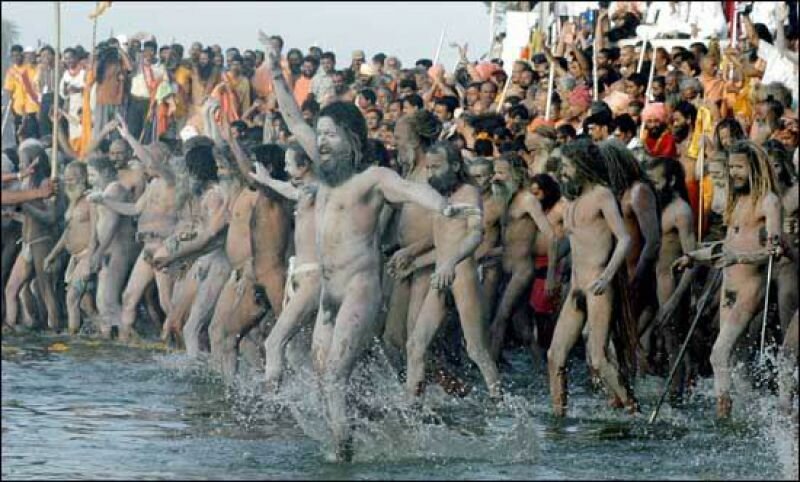

My interview with Sheldrake was a part of a work called The Experts for which I interviewed a number of contemporary researchers and thinkers about the possibility of a non-anthropocentric relationship with the natural world. The video above includes a number of fragments from these interviews including the one with Rupert Sheldrake. The other ‘experts’ interviewed for the project were the Pit River shaman Floyd Buckskin, audio ecologist Bernie Krause, anthropologist Ida Nicolaisen, philosopher Jacob Needleman, wizard and paganist Oberon Zell-Ravenheart and sociologist Fred Turner some of whom also feature in the video fragment. The interviews were part of my project, The Damagomi Project, an ongoing archive that documents the history of the Damagomi Group; a group of spiritualists and academics that was active in Northern California in the 20th century. Through the project I am trying to create a new path which can be followed to address the idea of panpsychism. In this sense the archive represents a series of thought-experiments in physical form that try to approach the seemingly impossible task of stepping out of our own human perspective. More about the project here.

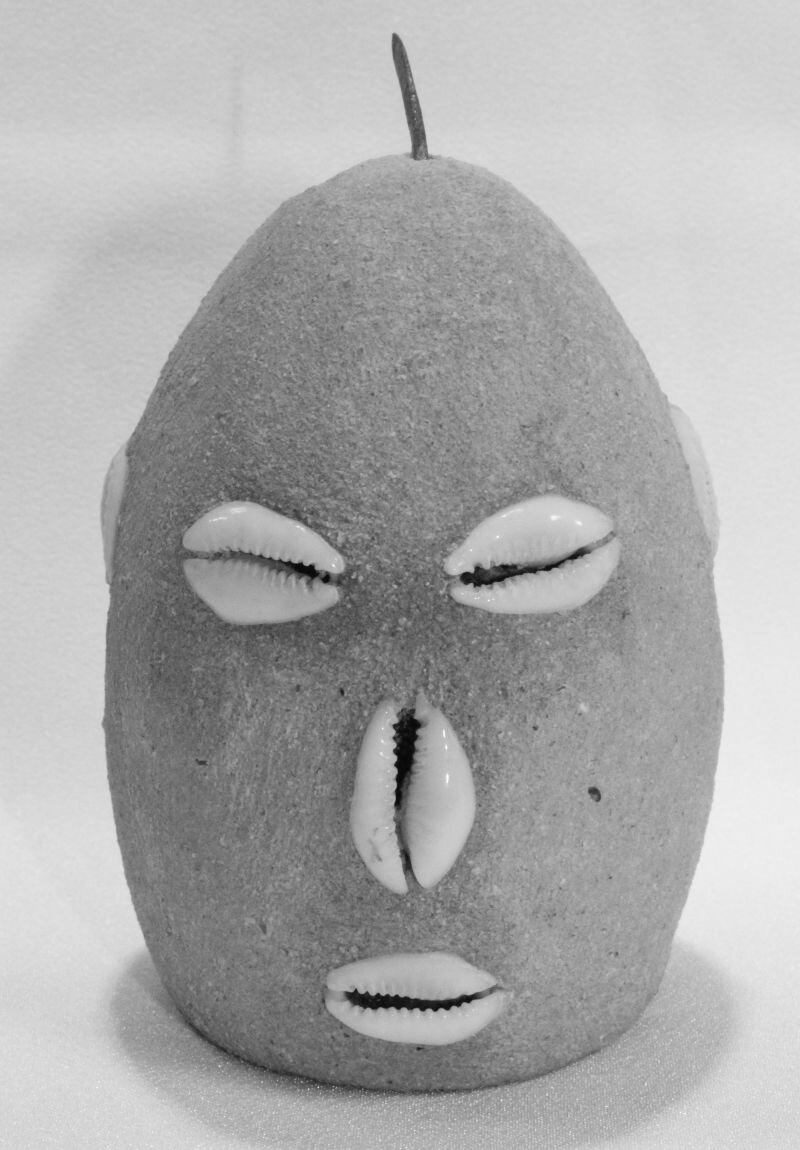

Floyd Buckskin is the last remaining shaman of the Pit River tribe of north-eastern California. I interviewed him in his bedroom that doubled as his music studio on the Pit River reservation to the east of Mount Shasta, California. In the interview he told me the word damagomi comes from the Achumawi language, a language still spoken by a small population of Pit River tribe. It translates roughly as ‘spirit guide which provides a channel of communication with the natural world’. The damagomi usually takes on the form of a particular animal and this animal will accompany an individual as long as their bond is honoured. When I asked him why the Pit River people searched for their damagomi Buckskin answered ‘We are trapped between spirit and animal. We aren’t one or the other, but both and because of this we need help.’

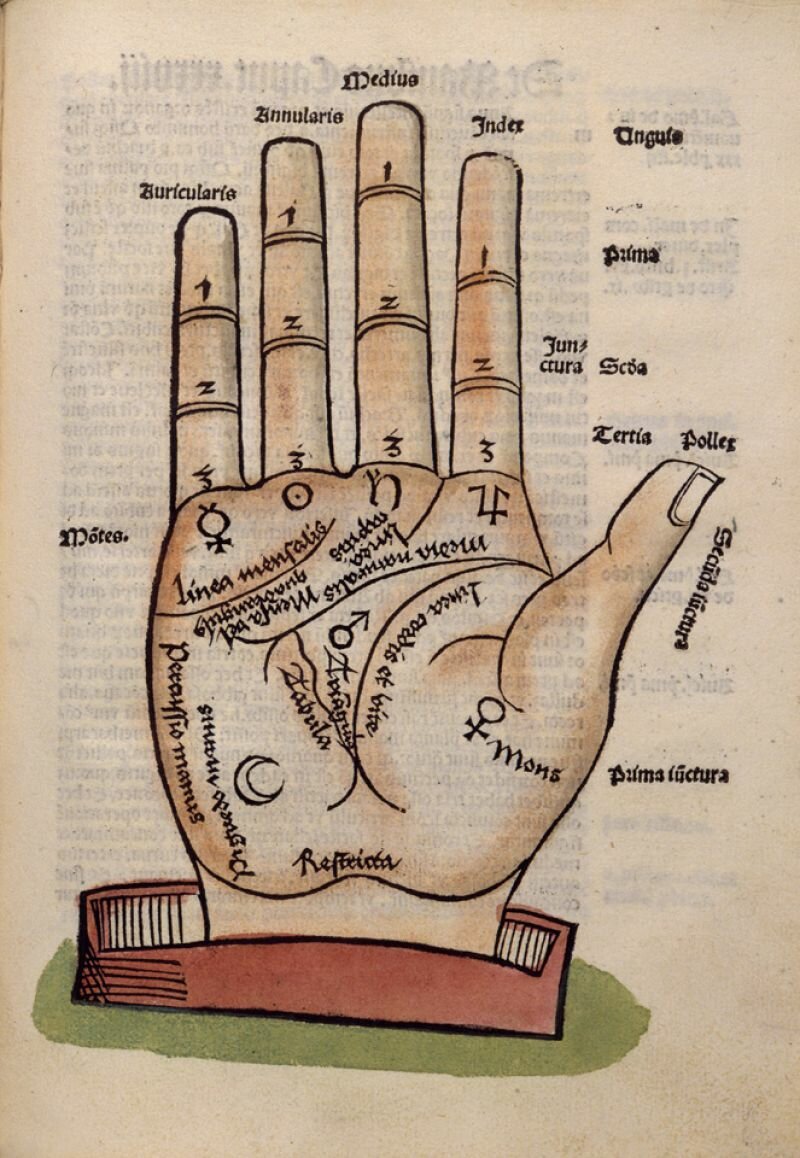

Towards the end of my interview with Rupert Sheldrake he mentions the idea that scientists (and I would add artists) are our modern answer to shamans; ‘members of the human community who are dealing with the natural world.’ In this sense they are instrumental in trying to bridge the gap between spirit and animal that shaman Floyd Buckskin describes. However the very language with which we have tried to describe nature with has come to define our view of it to such an extent that we are unable to see it at its most vital. When we look at the natural world through the lens of our scientific tradition we can only do so by breaking it into ever smaller pieces. The whole, as in the whole organism or being or galaxy, is often only considered through the sum of its parts. This is the metaphor of the machine which is essentially static and dead. In The Science Delusion, Sheldrake attacks this simplistic perception of the universe:

‘Science at its best is an open-minded method of inquiry, not a belief system; it has been successful because it has been open to new discoveries. By contrast, many people have made science into a kind of religion. They believe that there is no reality but material or physical reality. Consciousness is a byproduct of the physical activity of the brain. Matter is unconscious. Nature is mechanical. Evolution is purposeless. God exists only as an idea in human minds, and hence in human heads.’

According to mythologist Joseph Campbell the shaman should have the dualistic approach of understanding the world around her/him through mechanistic and empirical as well as the spiritual and holistic methods. I think the contemporary artist is perhaps somewhat better positioned to consider systems from the perspective of the living whole than the contemporary scientist. This is mainly due to the holistic nature of the creative process. The creative process requires a dialogue or push back from an other, alien influence. This can be through a concept, material or human collaborator(s). Without this push back the process remains static and you are not able to create anything new. In this sense the process must be ‘alive’ for anything of interest to happen. It must ride the line between defining the context of the artist and being defined by it.

I can imagine a kind of damagomi facilitating this exchange, providing the bandwidth that allows us to access the anima mundi. What are the repercussions of following this line of questioning and assuming an existing anima mundi contains our entire consciousness along with that of all living things? Or to follow Sheldrake’s way of putting it; is the act of making art merely the fusing of the morphic resonance of various beings and materials within the temporary morphogenetic field that is an art practice?

I think it might be time for a damagomi finding quest.