It was the groom himself who rang me. “We’ve decided,” he said, “that you’ll be saying a few words at our wedding.”

“At your wedding? Speak? But why? I’ve never even been married. What do you say, because of art? Don’t you know that in art most marriages fail sooner or later? A good marriage easily slips into the realm of the kitsch—how do you make art out of that?”

He merely laughed, showing that he wouldn’t relent. He knew all too well that I’d feel too honoured to decline.

“So you’ll do it!” he concluded.

“Alright. One word,” I said, and immediately began to think.

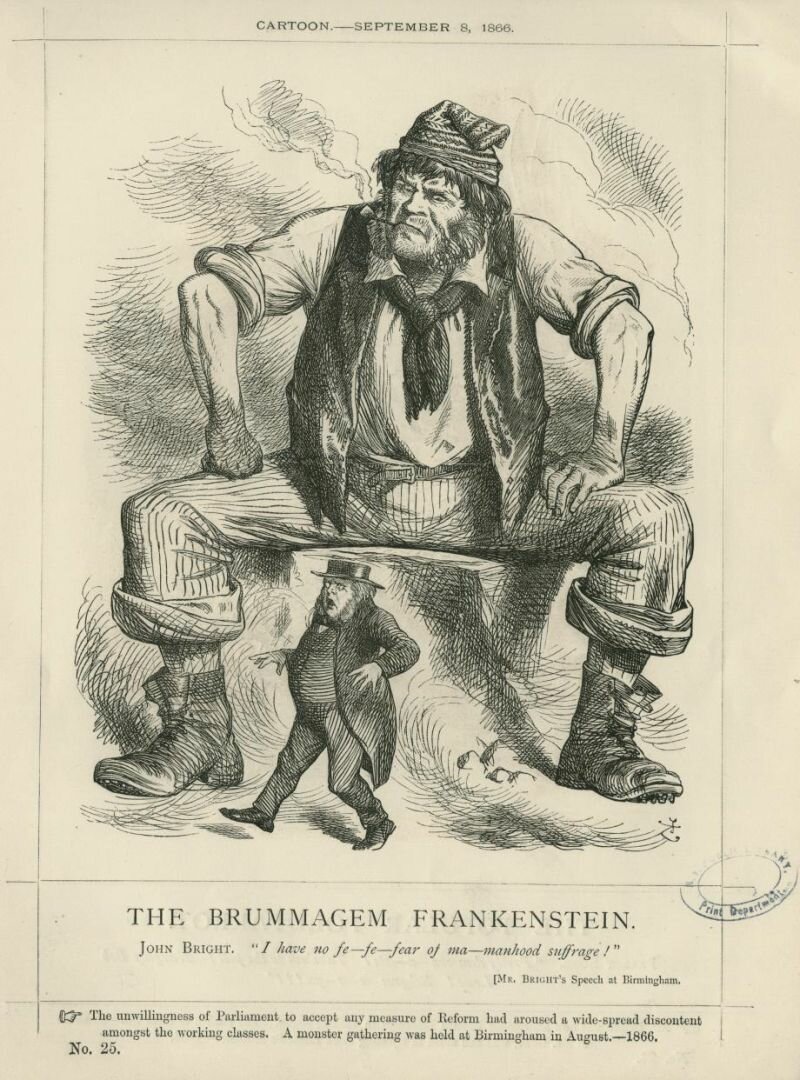

The first image that occurred to me was the marriage portrait of the Arnolfini’s, painted in 1434 by Jan van Eyck, a world famous painting that hardly ignites the desire to wed. The newlyweds stand soberly, sunken deeply into their own thoughts, nearing a state of melancholy. They make no eye contact with one another, they do not embrace; in fact, their only contact is made through their outstretched hands. And there, at that sole point of contact, does the painter place a small detail on a “coincidentally” positioned piece of furniture: a grinning monster, the quiet witness gloating at a depiction of hypocrisy.

The grinning crony, in turn, brings to mind another image, a photograph shot by Elliot Erwitt in Siberia in 1967. A young bridal couple is seated in a row of chairs in what seems to be a waiting room, poised respectably next to one another, freshly starched and groomed. Although we see the man and woman on the most beautiful day of their lives, their body language gives away their inability to make themselves the main attention of the events. With a mixture of distrust and admiration they look at the one who succeeds in overtaking the limelight: a young man seated one chair further radiating an air of freedom and independence, his expression hinting at some inside joke that threatens to burst into wild laughter at any given moment.

Although these images speak a thousand words, I was fairly sure that they would fail to bring me closer to my wedding word.

I decided to call in an expert, someone I knew well, who not only had been married for more than fifty years but who had also for years, as a sort of hobby, conducted a number of weddings every week. During these ceremonies, he’d also spoken, but about what exactly?

“About love, of course!” he exclaimed through the telephone. “Love is everything, stronger yet than faith and hope. Believing in what you will and hanging on to hope until you whither away essentially takes place within a vacuum. Love, on the other hand, is oxygen, breathing, and letting breathe. One thing I always say during a marriage is: the art lies in allowing the other to be their own person, and all you need for that is love.”

“Aha, all you need is love!” I said.

“Yes, that’s how you could summarise it.”

I thanked him heartily and thought for an instant that my problem was solved. After all, couldn’t I just step forward when my turn came at the wedding, look at the bridal pair, say “All you need is love,” and leave it at that? Every guest would understand me instantly regardless of his or her age, martial status, or nationality. I’d avoid testing anyone’s patience and all could feast themselves on cake with that great universal truth still resonating in the back of their heads.

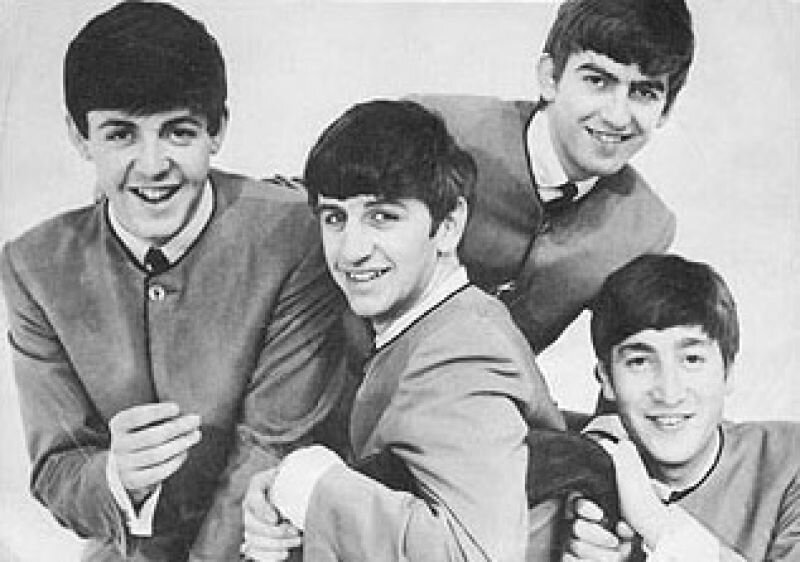

But I’d conveniently forgotten something: all you need is love had already been sold twenty-five years previously! Yes, in a fit of anti “love” and Beatles, I’d dumped all my LPs, EPs, and singles at the second hand record shop, including Magical Mystery Tour, on which All You Need is Love is the closing song. From one day to the next, their song suddenly sounded excruciatingly weak, yes, even whiny. The saccharine swooning on I Want to Hold Your Hand, for example was boiled down to kindergarten love.

Not long afterwards, the effectiveness of my manic clearing session proved itself when a crazy American calling himself Captain Beefheart, shouted “Rather than I wanna hold your hand, I wanna swallow you whole,” on his record.

During those days, although there were many people who rejected the “love cult,” they couldn’t prevent “love” turning into one of the most democratised word of all time. In time, the letters were substituted with a heart so that even the most seasoned illiterate could easily write and recognise the word, read it on cars, clothing, kitchenware, and everywhere else:I ♥ New York, I ♥ my dog, I ♥ Ponypark Slagharen, and so forth into infinity.

“Love,” was holding one another’s outstretched hands like the Arnolfinis. It was the love of that wedding couple in the Siberian waiting room, a love that had yet to be constructed, but whose foundations already shook at the mere grin of their happenchance neighbour. The Beatles sang “love is easy,” and it was indeed as such, as easy to get involved in as to subvert.

How vastly the difference was with the love that yearned to envelop the other in his or her entirety. That love was so much more worrying and full of risk, but likewise great and grand, yes, more royal than “love” had ever been. This was the love that, deep at heart, wanted nothing more than to possess and to be the other. It was a love that refused to “let the other be their own,” that ship had sailed miles before. Instead of “easy,” this love lacked compromise and could never live up to expectations.

It was all too clear: there was no way I could use “love” for my wedding word. If I wanted to communicate something truly valuable to the newlyweds, to wish them a love of the second sort that, of course, was related to and in conversation with, but far exalting, “love.” But how would I name this love? There was no word for it!

What could I do?

Extend my thoughts beyond fine art and pop music into the world of language, of literature.

I stepped into a small bookstore and struck up conversation with the sole salesperson.

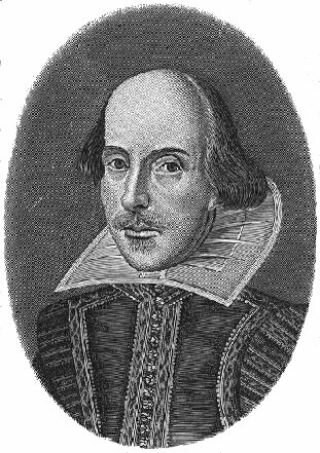

“But sir,” she said, after listening to me patiently, “it must be obvious that the word you’re looking for doesn’t exist. After all, if it did, these giant tomes on the subject of this love of yours would never have been written. It’s because love doesn’t allow itself to be captured in one word. Even the greatest literary genius, let’s say Shakespeare, if he’d ever found that word, would have quit writing immediately.

“Are you sure about that?” I answered, suddenly full of desire to buy something from her. “I’ll have one of those tomes!”

“You ought to take this,” she said, “Married Life by David Vogel.”

Once at home, I immediately began to read. From the start, I identified with the protagonist, accountant Gurdweill, and held onto that for as long as I could. How hard he tried to fight his way through life, and how much he suffers for the Barones he married! I had never read a book before in which a husband wants his wife be to her own person to quite the same extent. He wants this to the extent that he allows her to bully, humiliate, and taunt him after she returns home from one of her private parties.

At a certain point, out of the blue, I shouted: “ Do something, numbskull!” But just as that thought begins to enter him, his wife tells him she’s pregnant. And because there’s nothing he desires as much as a son, he uses this revelation as an opportunity to throw himself once again into a sea of sacrifice.

The sense of foreboding is beautifully sketched within the novel, the sense that all will only worsen—and it does. After caring for and cherishing his son for some time, he discovers what the rest of the village knew all along: the child isn’t his. And the worst part is that this discovery refuses to enter his consciousness, for the simple reason that he cannot believe it. It seems that, rather than being a master in sacrifice, he’s a master in self-deceit.

This wonderful book, Married Life, is all about love that lacks a word. Because the greatest love is not Gurdweill’s, to which 450 pages are dedicated, but it’s the love of Gurdweills acquaintance Lotte, to whom few words are granted. Even Lotte hardly speaks of love, not because she wishes to spare her fiancée (with whom she shares a simple “love” relationship,) but because she wants to respect the marriage of the man she truly loves, Gurdweill. Her wordless love is the grandest, not because of her suicide through which she proves her self-sacrifice to be even greater than Gurweill’’s, but because she offers him insight into his own existence through that ultimate act. Her death grants him life, and he finally awakens. Ultimately, on the very last page, he takes action. What he does is horrible, but at least it’s something.

When I walked past the little bookshop again some days later, I saw the sole shopkeeper unpacking boxes. I went in and hesitated. Suddenly I said, “That book wasn’t very festive.”

“No,” she laughed, “great literature rarely is. Even a genius like Shakespeare is never festive for long, and especially not when it comes to married life! But, wait a minute, something just came in. It might just be something for you.”

She held up In-House Weddings by Czech author Bohumil Hrabil.

Across from the little bookshop lay a park, and because it was the first sunny day in a long while, I crossed the street. As I sat on a bench between the trees I thought to myself: wouldn’t this be a fine day for a wedding? And in the best of moods I began to read.

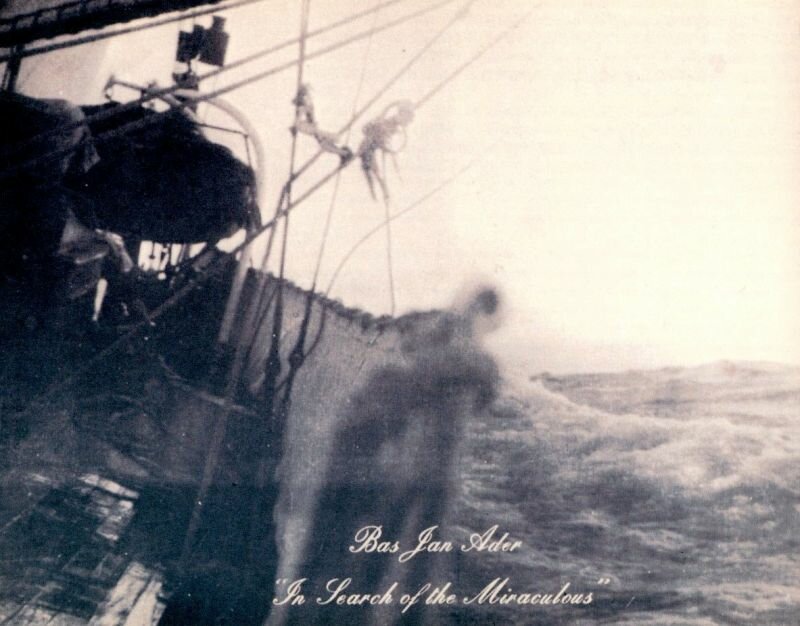

It was immediately clear that In-House Weddings was about that certain type of love that I knew no word for. It seemed that the writer had been especially aware of that essential problem in all great love affairs: the impossibility to ever become one. The author attempted to find a solution and by wonder and sheer ingenuity, he succeeded.

Hrabal writes this autobiographical novel in the first person but the “I” is not him, but the woman he’ll marry at the end of the book. Thus, he crawls into the persona of his fiancée to describe himself, and in doing so demonstrates that it’s just about two things: possessing the other and being the other. In the book, he not only is his wife, he ultimately has her too.

The writer has his fiancée (who consistently refers to him as “the doctor”) speak of the things they undertake together in the time before their marriage. In one of the many beautiful scenes, she speaks of how he shows her around the area. On a sunny day they board a train, where the legs of travellers dangle from the coaches. The constriction of the overflowing balcony drives them to find the only free space—the toilet. Their lips meet in a passionate kiss for the first time there, above the cracked and grimy toilet bowl. Tender words follow, like: “’I always feel so fine with you” the doctor whispered in my ear.’ ‘As do I,’ I said./ ‘Because when I’m with you, it’s almost like you’re not even there,’ he mumbled.”

How grand! To be so intertwined with your lover that their presence is no longer felt: in other words, to no longer be perceived as the other. How superior compared to the meagre “allowing the other to be their own!”

More than anything, the wedding party is a beer drinking party for the doctor. The neighbours explain to his fiancée that, as a sort of hobby, the doctor scans the wedding announcements each Friday and always invites the guest for a wedding party at his house. In other words, “that they’ll be drinking, they’ll drink and sing without abandon…”

Yes, In-House Weddings was definitely a festive novel. Forgetting the time, I’d sat through many moving and optimistic moments on the bench that summer’s day. But while I made my way home, something began to gnaw it me. Because, although I knew more than before about married life and wedding parties, I hadn’t thought of that one word for a moment. In fact, Vogel and Hrabal had mainly distracted me. Oh well, that solitary saleswoman was right: the word didn’t exist. Just forget about it, I told myself, get that idea out of your head.

I got home, opened a beer, sat myself in front of the television, opened another beer. Being bored to death – and I’m still unsure how it happened – I suddenly held The Complete Works of Shakespeare in my hands. Against my nature, I began leafing through it backwards. Printed on the last pages were a few poems, and a word immediately caught my eye after a few lines, the word “love.” Shakespeare and “love,” I thought immediately, poor Shakespeare! But as I continued reading I realised that in these sonnets “love” did not rhyme with words like “glove” and “above,” but on “prove” and “move!”

I read how the poet takes his fiancée on a stroll. He takes her to the top of a hill and shows her various points of interest in the landscape. And then, in the last two lines:

And if these pleasures may thee move

Then live with me and be my love.

It was unbelievable, Shakespeare had found it! That word that was related to and in communication with but far exceeding ‘love’.

Loev!

I closed the book and opened yet another beer, as though the wedding festivities were already well on their way. What a relief that I hadn’t had to plough through all of Shakespeare to find that decisive word written on those last pages. I haven’t a single doubt that love only appeared as “love” in these last sonnets. In fact, I was convinced that Shakespeare, once he’d made his discovery, must have stopped writing once and for all.