Museum Vrolik’s origin lies in the inner city of Amsterdam. Museum Vrolikinianum, the private collection belonging to Gerard Vrolik (1775-1869) and his son Willem (1801 –1863), was housed in Gerard’s stately home on the Amstel, not far from the Waterlooplein. During the ‘40’s and ‘50’s of the last century, scholars from all over the world flocked to the museum to marvel at its renowned collection. Father Gerard Vrolik, professor of botany, obstetrics, anatomy and surgery, collected specimens mainly in the field of pathological anatomy, a field that was rapidly emerging during his time. His son Willem, professor in anatomy, physiology, and zoology, preferred comparative anatomy and birth defects.

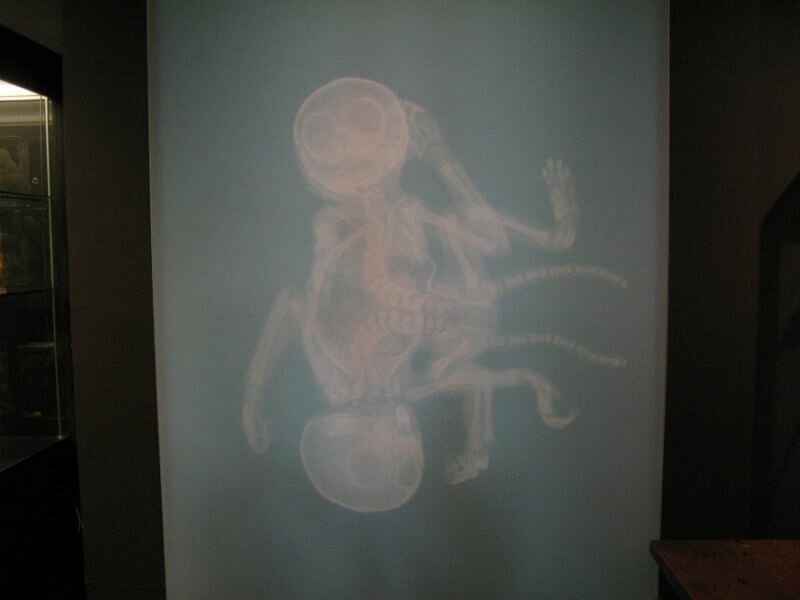

When Willem Vrolik died in 1863, the Museum Vrolik contained 5103 objects. Among these included specimens of rare birth defects such as ‘double miscarriages’, cyclopses and sirens, dozens of ‘sickeningly deformed bones’, two skeletons of dwarves, an enormous skull belonging to a man with hydrocephalus, and the skeleton of a lion once belonging to King Louis Napoleon.

Vrolik’s widow was keen to sell this enormous collection. The collection was headed towards being taken apart and shipped off abroad. A group of prominent Amsterdammers felt that this would be a great loss for the city. They bought the widow’s entire collection and granted it to the Athenaeum Illustre, the forerunner to the University of Amsterdam.

Museum Vrolik was the last great private collection of its kind in The Netherlands. From the ‘50’s and ‘60’s, the ‘ordinary’ anatomist was no longer concerned with illnesses and thus the amassing of collections in the field ceased. Furthermore, Darwin’s theory of evolution (1859) sparked a whole new perspective on the development of species. In Vrolik’s world of ideas, a divine “power of formation” was still seen as the driving force to develop a living being, but Darwin’s theory of selection dispelled this thought.

The Vrolik collection forms, as it were, a time capsule of the moment just before large-scale medical and scientific changes would usher in a new scientific era. The scientific spirit of the Vrolik’s nineteenth century remained within the collection.

In the current Museum Vrolik, an entire wall in the exhibition is dedicated to portraying the Vrolik collection’s broad inclusion of that 19th century spirit. Two display cases covering the entire wall and a historical cabinet show human skeletons and skulls diseased with rickets, scoliosis and syphilis placed next to organs of a great diversity of animal species as well as both normal and deformed skeletons.

Since September 2012, the Museum Vrolik’s permanent collection has been completely renewed. The ‘new’ Museum Vrolik is truly a museum of collections with more than a thousand preparations, skeletons, and skulls. There is no clear route within the museum: one can wander through display cases and be amazed at a congenital defect, at how we are built; they can explore, wonder, and make comparisons.