By coincidence, I stumbled upon a big slide archive that contained more than six hundred old Kodachrome slides. The owner, a blonde lady, who I estimated to be her forties, and who I previously contacted about picking up some vintage audio equipment, saw me looking at the big pile of yellow squared boxes and asked me, ‘Are you interested in this photography stuff?’

‘Yes I am very interested!’ Inside my hart almost stopped, knowing these boxes must be full of slides.

‘Okay, you can take them,’ she replied, ‘the person who was supposed to pick them up never replied.'

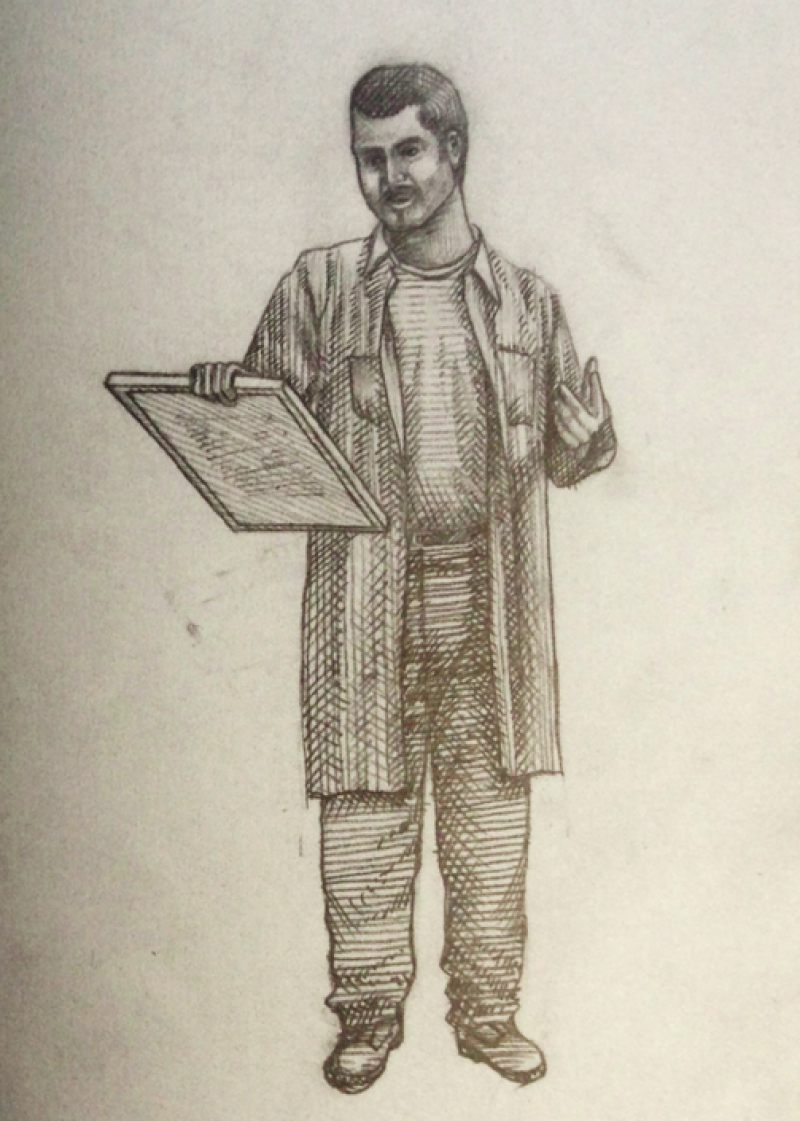

I continued the conversation and explained that as an artist, I work with found footage. She replied that she understood the importance of saving cultural heritage. Happy as a child, I left with my newfound treasures: the boxes of Kodak slides, some 8mm films, analog film/photo cameras and the audio equipment.

Looking at the first slides from my projector at home I recognized her on the family photos, they contained a big part of her childhood. I wondered if she had made a mistake by giving them away? Suddenly this question felt awkward for me, usually I don’t have contact with the owners of my found footage and they remain anonymous for me. I wondered if I should return them but my curiosity won me over.

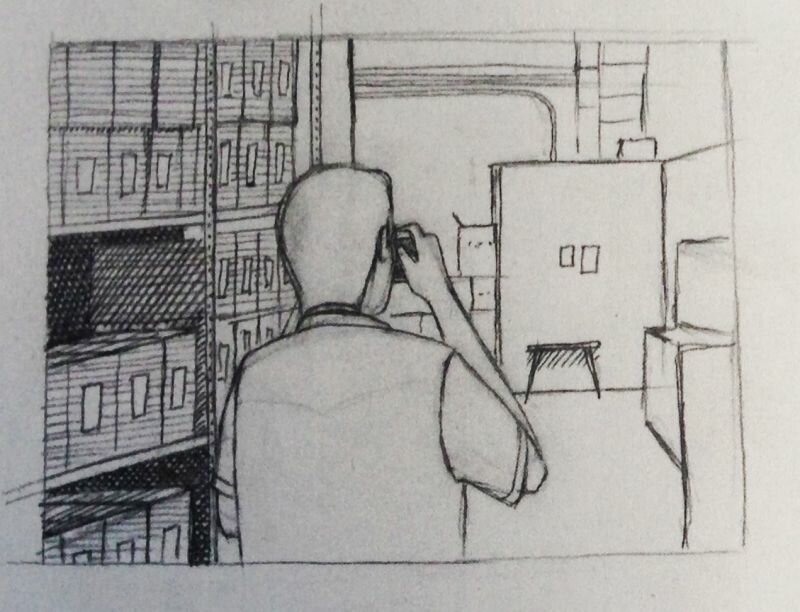

After carefully reviewing all of the images, I selected, re-arranged and scanned nine photos in a period of two weeks. I sent them to her via a private message as a surprise, thinking she would like seeing the photos. But it also felt weird to not ask her permission before publishing them.

This situation in which I had to ask permission proved to be a nerve wrecking experience, because there was always the possibility that she’d want the photos back! After a while she replied, a bit shocked, because in a quick glance all she had seen were the pictures of herself. She wrote me: ‘Who are you and why do you have photos of me!?’ I can imagine it’s kind of creepy, seeing pictures of yourself sent to you by a stranger!

After reading the full message with my concept in it, she luckily replied that she was fine with me making a series of the slides. Still, I felt puzzled as to why she gave them away, but who am I to disagree? She felt that it wasn’t important for her to be mentioned in the credits and asked me to remove the last photo in the series. It's been three months now and she hasn't showed any interest in the slides at all.

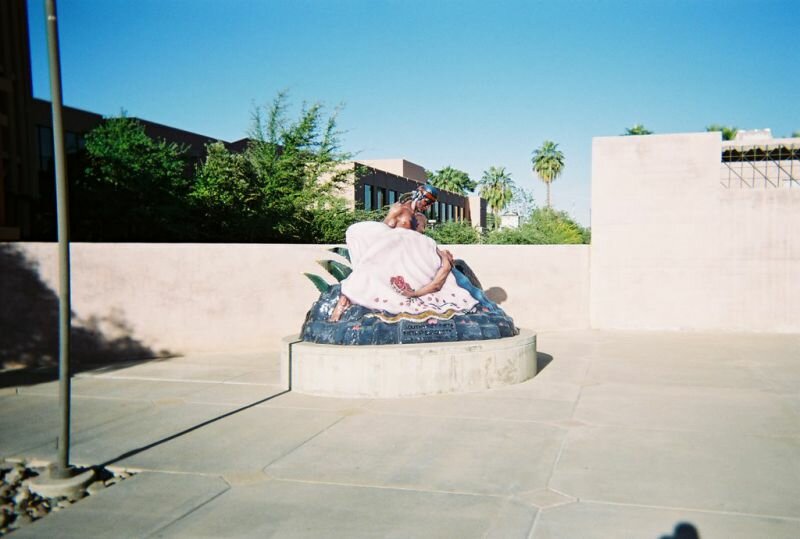

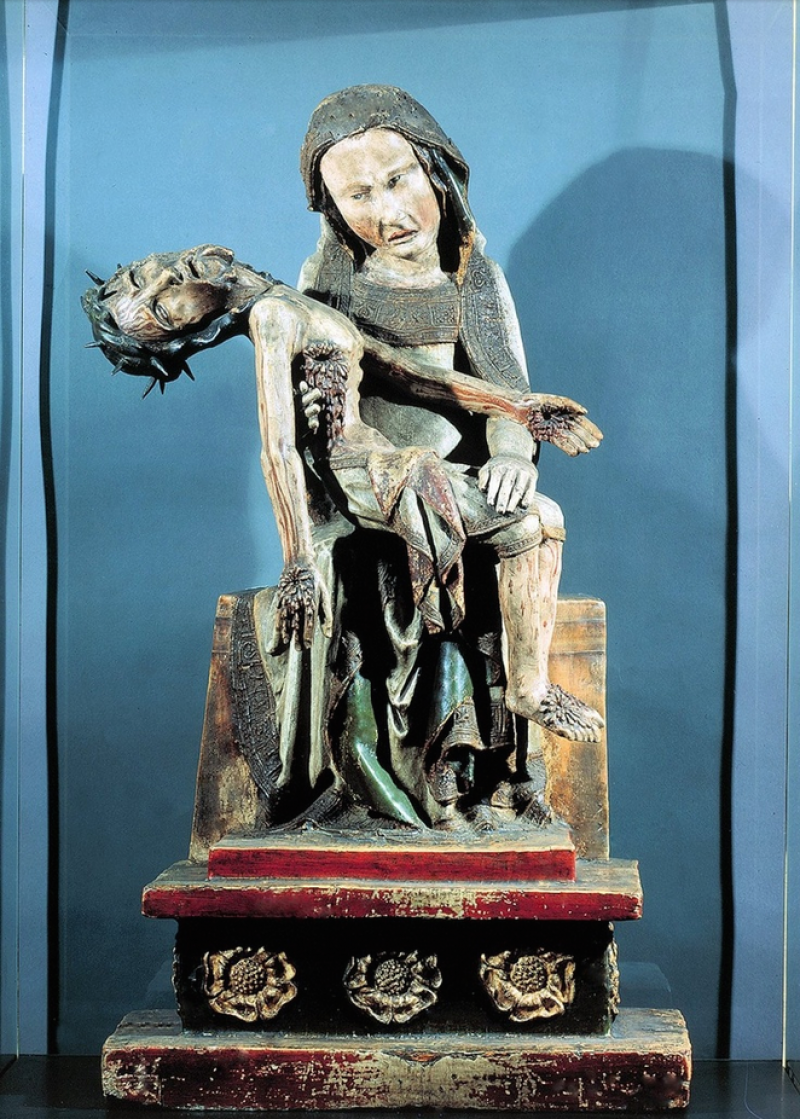

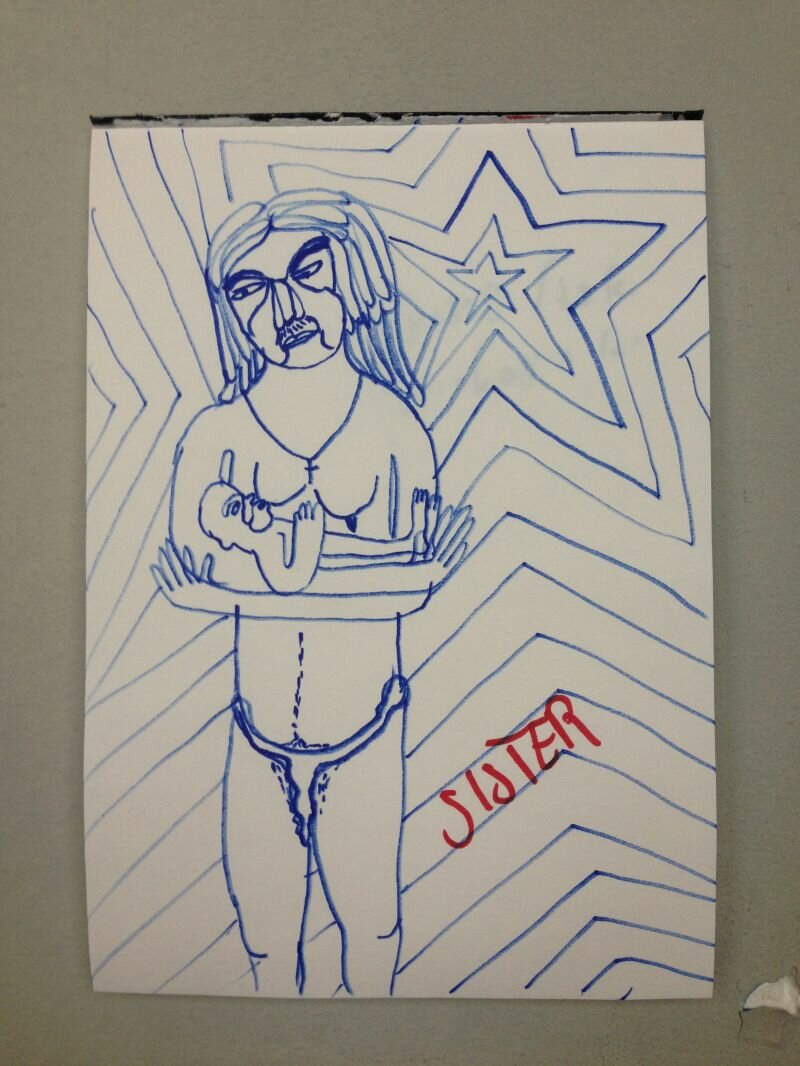

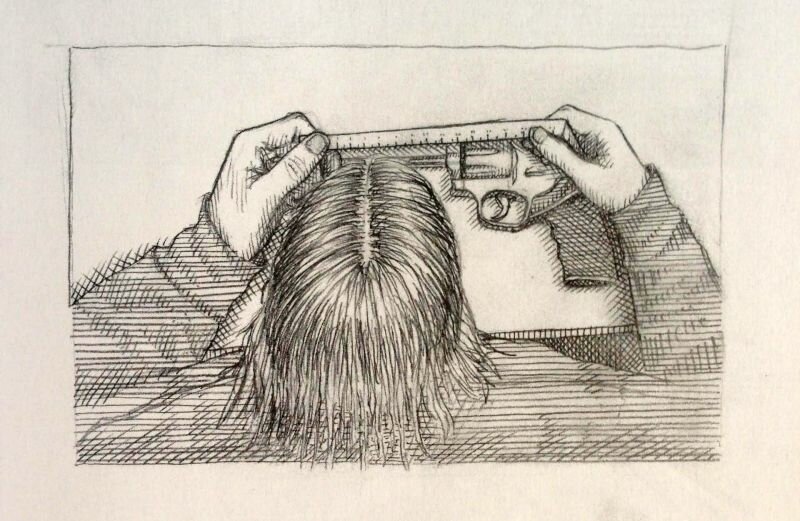

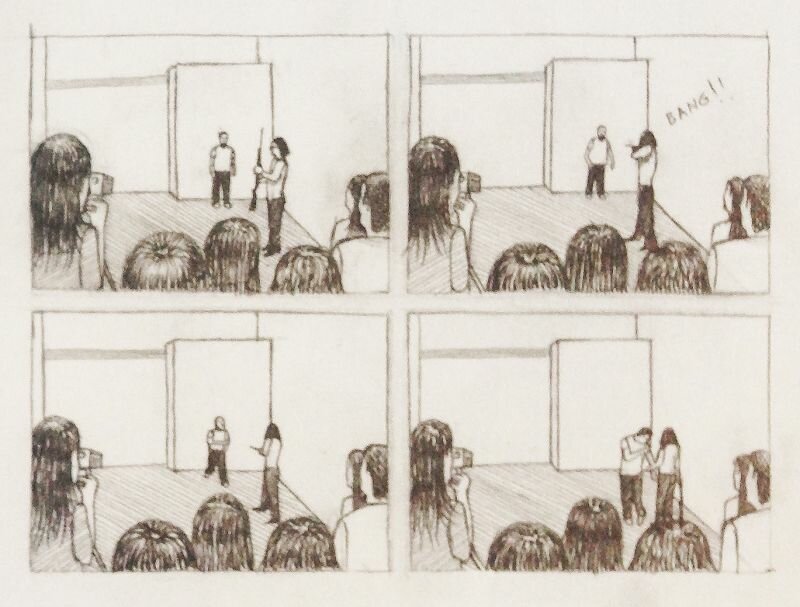

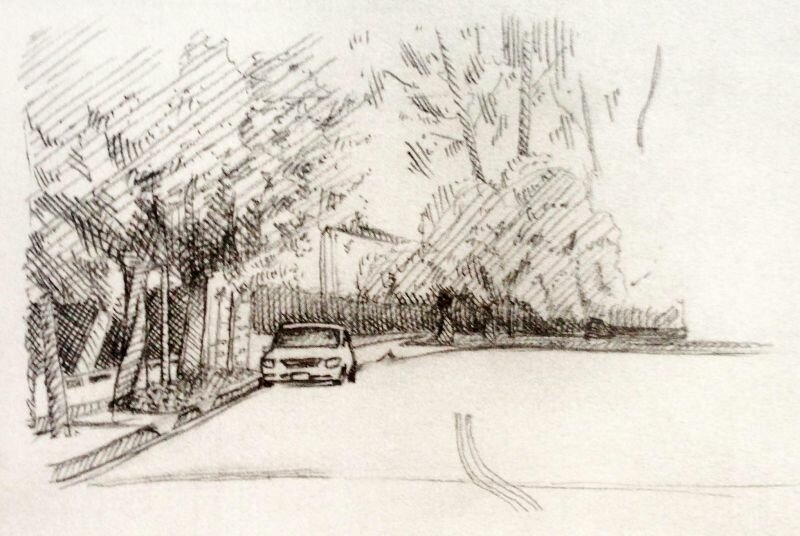

So here it is: the series titled ‘A.k.a. the life of’ tells the story of a young child growing up into adolescence seen through the lens of her parent(s). The photographer, I think it’s her father, made an effort framing, staging and capturing the child’s discovery of new things, holidays, road trips, playfulness, love for animals and finally as a teenager looking into her own reflection, slowly forming her identity as a young woman.

I have a background as an experimental filmmaker and believe that each image contains its own story and I treat the found images as if they were frames from a film that is in the making. By thoroughly scrutinizing flea markets, second hand shop and even waste dumps, I find, collect and scan photographic and slide images. By re-arranging this media I try to create new narratives to give existing material a new context.