JUST CALL ME DAD

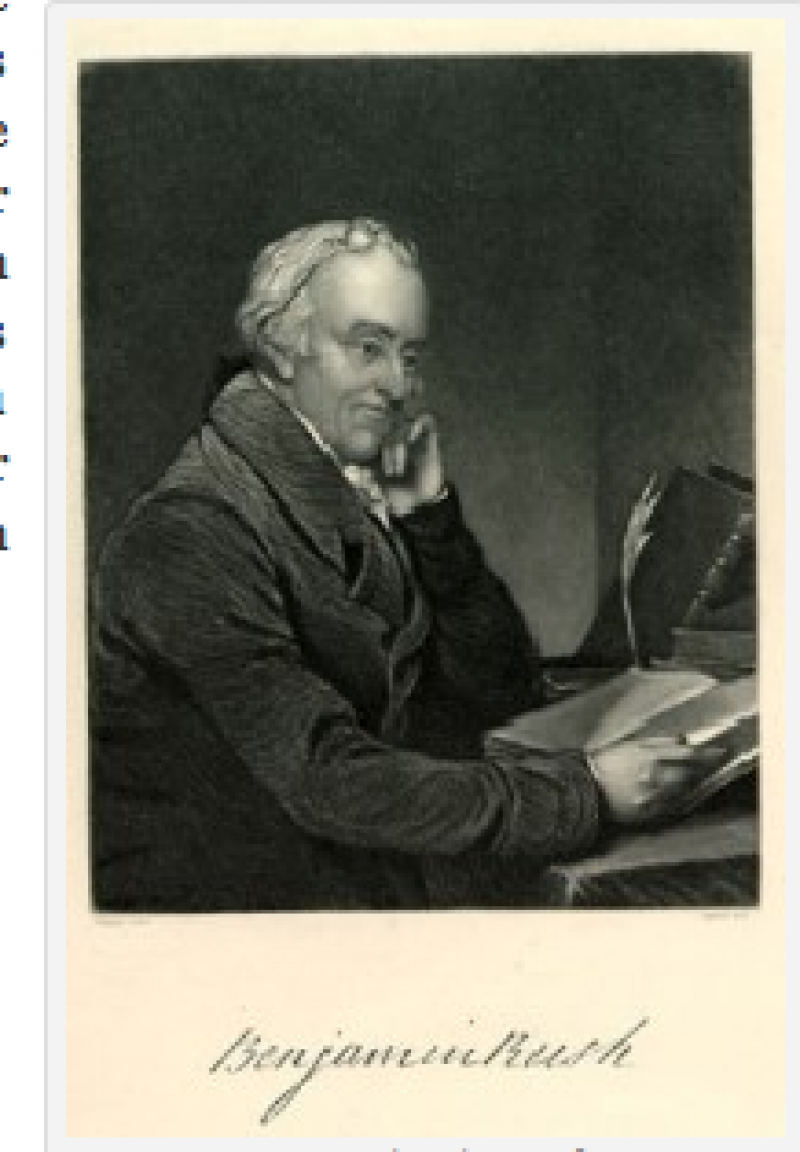

Benjamin Rush is often referred to as “the father of American psychiatry,” and indeed his portrait still adorns the seal of the American Psychiatric Association. In 1965, the APA placed a bronze plaque by his grave at Christ Church Cemetery in Philadelphia, affirming and consecrating his paternity.

Rush’s seminal opus, Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind nowreads like a primer for psychological torture. Suggested punishments for the misbehavior of mentally ill patients include tranquilization through the imposition of physical restraints; food modification or deprivation; cold water treatments; and prolonged shower baths.

“If all these modes of punishment should fail of their intended effects, it will be proper to resort to fear of death.”

Other fears also come in handy, as well as an acute sense of shame, though Rush asserts that because of some neurological process he fails to specify, the patient will have erased all memory of such fears, once returned to mental health. Also, we should note Rush’s deft distancing from the brutal exercise of the whip; clearly he prefers other more refined techniques.

FROM CHAPTER VI, TREATMENTS

In many cases, the line between punishments and treatments is quite flexible within the medical philosophy of Dr. Rush. Thus the tranquilizer performs a highly useful secondary role in facilitating the application of other treatments:

“The tranquilizer [chair] has several advantages over the strait waistcoat or madshirt. It opposes the impetus of the blood towards the brain, it lessens muscular action every where, it reduces the force and frequency of the pulse, it favours the application of cold water and ice to the head, and warm water to the feet, both of which I shall say are excellent remedies in this disease; it enables the physician to feel the pulse and to bleed without any trouble, or altering the erect position of the patient’s body; and lastly, it relieves him, by means of a close stool, half filled with water, over which he constantly sits, from the foetor and filth of his alvine evacuations.”

On the website of the Pennsylvania Hospital, the tranquilizer is described as “doing neither harm nor good.” The statement is made without reference to any supporting documentation or testimonials from patients or doctors:

Though Rush mentions in his book that a fully functioning tranquilizer was used by the hospital at the time of publication (1812), I have been unable to confirm its present existence as a physical object; a copy of an engraving endorsed by Rush as accurate appears on the

website for the U.S. National Library of Medicine:

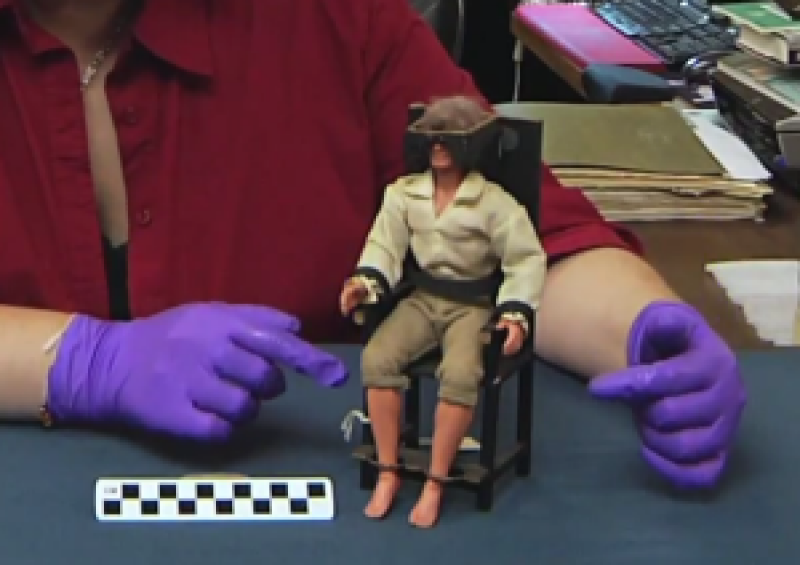

A small scale model of the chair on display at the Mütter Medical Museum, also in Philadelphia, shows a rather different device (purple gloves belong to Mütter curator Anna Dhody):

DISPLAY MODIFICATION

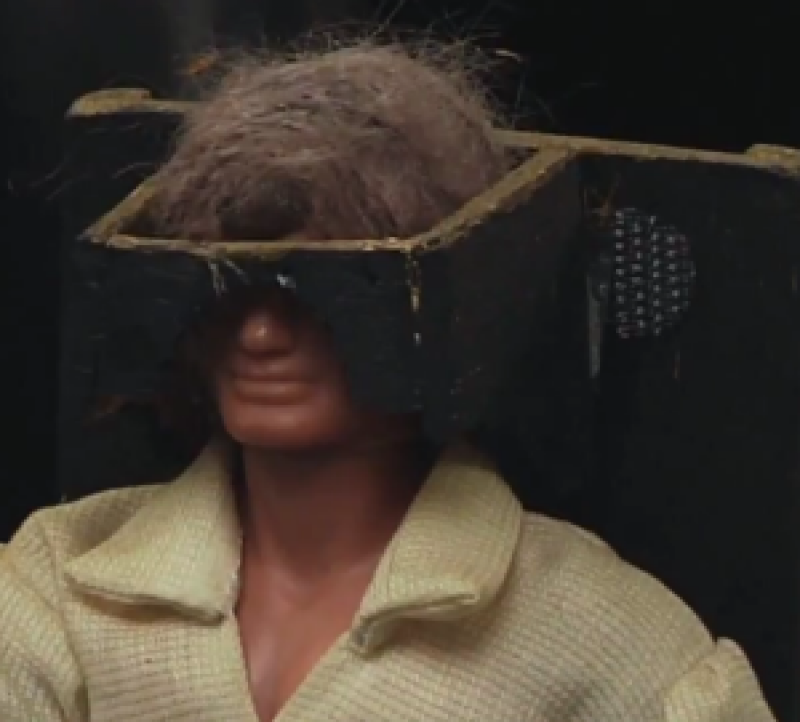

Of particular note is the absence of the “close stool”; and the innovation, apparently devised by the model maker, of the blinders. With this modification in place, the patient can neither move his head nor bear visual witness to anything happening within his environs.

It is possible that the design change was introduced by the model maker simply to make the head structure more durable, yet whatever the explanation, the modification is remarkably prescient in anticipating a key attribute of contemporary psychological torture as

developed by the CIA since the 1950s: the merging of corporeal restraint with sensory deprivation and/or perceptual disorientation.

NO TOUCH TORTURE

Interestingly, the two most recent recipients of the APA’s Benjamin Rush award, together with the titles of their lectures, are:

2008

Mark S. Micale, Ph.D., Associate Professor, History of Science and Medicine at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.Psychological Trauma and the Lessons of History.

2011

Andrea Tone, Ph.D., Professor and Canada Research Chair in the Social History of Medicine, McGill University. Spies and Lies: Cold War Psychiatry and the CIA.