21.11.2013

08.10.2013

At my office in The Hague, I called my doctor and made an appointment for the following morning. My colleague Jan Willem asked what it was I’d been suffering from and as I described my symptoms to him, the pain began and started steadily increasing. Unlike before, the pain didn’t stop after some minutes but persisted and slowly worsened. Breathing became difficult, and I felt like I needed to go to the toilet.

Slowly, clarity began to disappear from my consciousness and I tried to find a comfortable position in one of the two Gispen armchairs where Jan Willem and I can often be found, lounging and philosophising. Thinking I was hyperventilating, Jan Willem handed me a plastic bag to inhale and exhale into, to no avail. From that moment, I found myself in a state of unconsciousness where I still was aware of my surroundings but could not in any way exert an influence on what was happening. I could hear Jan Willem on the telephone, but I could no longer understand him.

After a while, the office filled with men who groped and examined me and made me swallow a handful of pills.

‘I bet you feel a lot better already,’ I heard someone say. I was unsure if it was directed towards me, although I suspected it was. I didn’t feel better, but I also didn’t feel any worse. I was completely apathetic towards anything happening around me. Two men held me between them and carried me down the stairs, placed me on a rolling gurney that was pushed into a car. We drove straight to the hospital. I heard the siren but didn’t understand it was me that it was wailing for.

Inside the hospital, I was given a quick look over by the emergency aid doctor. At this point, I was becoming more and more detached from my surroundings. I was in a whole other state than the world around me. My body was nothing more than an empty casing inside which all coherency was lost. The immateriality of my physical self started becoming apparent. I was no longer aware of my external form. Skin, bone, fluid, flesh, all dismissed. Like a ship in a bottle, I had escaped my glass vessel. It no longer contained anything, yet it was simultaneously all. The ship, too, was nowhere to be found.

‘This isn’t going well at all,’ the emergency doctor said. I definitely heard him, but I had no idea if it was me who he was referring to. In any case, I didn’t care. Later, Jan Willem told me that total panic had broken out in the emergency ward, that everyone had dropped what they were doing, leaving patients dumbstruck in the midst of their treatments, and that I’d been rushed to the operation room in a frenzy.

I was fine with everything, letting it all come over me. I felt an intense euphoria. I was completely satisfied with myself, my life, and everything I’d done up to that point. I felt no regrets, neither remorse nor resentment. All was good. Nothing mattered. In the meantime, I was hooked up to an IV, and a hollow needle was punctured into my groin. I certainly noticed these happenings, but I didn’t care. The doctor leaning over me spoke unabatedly, describing his actions. I didn’t care and only mumbled incoherent meaningless responses, Surrendering myself to the euphoria, I felt all become one, and I felt one with the nothingness, dissolving into my body. And then, all of a sudden, I was back to my senses.

‘You see,’ said the doctor, ‘we got rid of the blockage. I’ll now widen the coronary artery by placing a stent, so we can get enough oxygen to your heart again.’ Disappointed at being ripped from my euphoric state and back into this banal situation, I stared at the monitor and watched the cardiologist put actions to words. He explained I’d had a heart attack that he’d put an end to by performing an angioplasty.

I was placed in intensive care for a day and a half, spent a day in recovery before being allowed to go home. I underwent a speedy recovery and visited an artist in her studio that same weekend with whom I spoke nothing of my heart attack, keeping the conversation to her work.

What I learned from this experience is the personal realization that I did not mind dying in any sense. There is nothing awful about the process of dying. My experience was not religious, not even spiritual. The only way I could describe the euphoria I felt is as immateriality. Of course, I’m extremely grateful to those who prevented me from dying, but at the time I had absolutely no qualms with bidding life farewell. I was prepared to surrender. There was no fear, I wasn’t scared. The pain was there, but became secondary; it never disappeared completely, instead it lost all importance. All that mattered was the realization that I had no more expectations of the world, and the world expected nothing more of me. I felt united with who I was. Everything made sense. There was no space between anything. No distance between finitude and infinity.

I truly believe that during this realization of inevitable mortality, the right side of my brain, in which the sensation is manifest that we are all part of a collective life force, united itself with the left side of my brain, where the sensation is held that we are, indeed, all individual beings separate from one another. The separation between the halves of our brain causes this latent schizophrenia in us all, but was dissolved in the knowledge that I am completely insignificant while I am unavoidably part of life, as we know it. That I, without a doubt, will perish doesn’t affect this conclusion. By dying, we dissolve into life.

Immateriality made manifest. It’s mostly our own bodies that shape its contour. Everything material that we realise allows us to experience something immaterial. Between our body and the matter to which we measure ourselves lies our incapability: all that we cannot and do not control. I’m convinced that this space between the things and us is what the artist uses as his material. What the artist makes is of no importance; instead it’s the meaning that the artwork can give to time and space. This implies that the work’s meaning is in a constant and dynamic state of flux. That which means nothing today, was indispensable yesterday but might mean everything tomorrow.

The artist is someone who manifests materialisations. His starting point is how he observes something, how he sees something. This is not in the first place, an awareness based on appearances, but instead on an inner experience. We can undergo this alone. We enter an artwork using our imagination. This is not a matter of creative fantasy, although there’s nothing wrong with that, but of the tangible capacity to express what we do not know, we don’t understand, and what we cannot.

07.10.2013

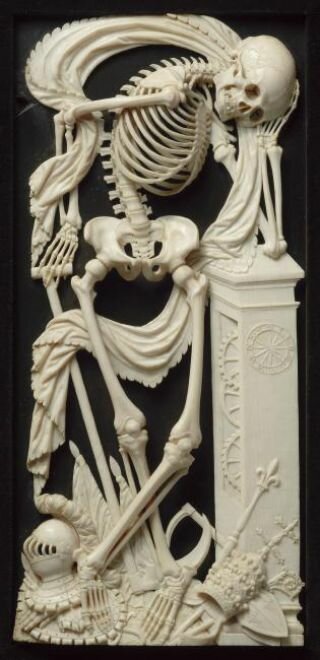

Death and life are inseparable. In the middle ages, this was manifest in a specific type of object, the ‘memento mori,’ which literally translates into ‘remember that you will die.’ In essence, the message is the same as the gnothi seuton (γνωθι σεαυτόν) of the ancient world, but instead of using the knowledge of impending death as an excuse to live life to the fullest, the middle ages focused their living days on ensuring that both the act of dying and the afterlife would be as painless as possible.

"What we (once) were, you are (now), what we are, you shall be (Quod fuimus, estis; quod sumus, vos eritis). Affluence, beauty, and fame will pass. Show penance for your sins and live a simple life from this day forth, then you shall live eternally in the glory of God."

Second half of the 16th century

KMKG

This text was written for the exhibition ‘Tussen Hemel en Hel. Sterven in de middeleeuwen’ in the Jubelparkmuseum from 2.12.2010 until 24.04.2011

07.10.2013

I only started living once death entered my life. Don’t worry, this is a tale with a happy ending. Until death entered my life, I was constantly accompanied by a certain desire for something better, something far-reaching. I was certain I would meet people endlessly more interesting than those I already knew. I would find myself in infinitely more exciting worlds. The bottomless well of the unnamed desire. I would be admired, doors would open, actresses, sultry nights would ensue. I might be overdoing it a bit, but there’s not a soul out there who won’t understand what I’m getting at.

Opera singers, spotlights!

Essentially, there’s nothing wrong with these daydreams, after all, you’ve got to have something to look forward to. But the medallion has a flipside. Whatever I experienced, whatever I did, it held no importance because it was no match for what was waiting for me. When it finally came, I was bored. And I remained bored.

I sat slouched in chairs and grumbled unintelligible responses to questions or requests. I just could not be bothered. Some might be familiar with this state.

What, in God’s name, is a dynamic existence? Ask those who lead them. It’s not as great as you’d think, they’d say. If it were up to them, they’d rather be sitting on the sofa with a plate on their lap full of mash and a dimple of gravy. It’s a cliché, and it’s true.

We’re all aware of our mortality. But few truly fathom this knowledge, nor did I, in the least. Quite a few people around me have passed on, many of them being the same age as I. I’ve been reminded of the inevitability of death countless times, yet it took me ages until it truly hit me. Open the newspaper, turn on the television: they’re dropping like flies! But every morning my eyes would open once again and another day of limitless days would begin anew. Time, I spent her as if she’d never run out. Body, as though it could not be broken. I needed to see death through the passing of those around me. I have photos of me with them. With the same indestructible body, and the same endless sea of time as I have before me. First a friend, then another friend, then my thirty-eight year old sister, and a year later, my father. This is the point where it started dawning on me. This is it. This is all there is. This is what I have to make do with, for however long I have. That, in retrospect, whatever it is, it’s already quite substantial.

During this period, I ended up in Germany for a group exhibition. My pictures were being shown. Now I’ll have a real experience, I thought (I’ll never completely rid yourself of that daydream.) The international art world, and I’m a part of it! Beautiful, eloquent women! Behind a large mansion they stood in a big garden, holding a glass in one hand, an hors d’oeuvre in the other. Naturally, I knew no one. I forgot to tell you that besides being easily bored, I’m also shy. I’m normally not shy, except at moments when I don’t want to be. Needless to say, I struck few conversations in that garden. But I wasn’t too excited by the people I did manage to speak to. All that talk about art. The perpetual name dropping of famous people. If they weren’t speaking of wildly famous artists, they’d be speaking of themselves. Show me one artist who isn’t smitten with himself. I was lucky to have brought a good book with me; otherwise I’d have been completely and utterly bored.

Everyone stayed the night in that big mansion, including myself, it had gotten late and my nerves had led me to drink quite a bit. Driving 400 kilometres to Amsterdam didn’t seem like a very good idea. That night I was dreading the thought of reopening my eyes the next morning to find myself faced with the same art world characters all over again. In that same garden. And talk, talk, talk of art and international destinations.

After breakfast I wanted to speed off, but I was stopped. There must be football, the artists against each other! Football? What a load of nonsense. I tried to worm my way out of there but to no avail; they pushed a pair of boots into my hands and dragged me onto the field.

I don the boots, step onto the field, the ball is passed to me, I give it a kick and I’m sold. Ever since that day, I’ve played football every week with the exception of flues, vacations, and injuries. There’s nothing that makes you as conscious of your body as running after a ball for an hour. It makes you aware of your existence, of your fully functioning body. The exhaustion, the glow, wonderful. Thinking of nothing but the ball. It’s slightly late to start football at the age of thirty-eight. I’ll never be very good at it. I don’t play competitively. There’s a bumpy lawn in Amsterdam where I play against ten, twelve friends. Never a day of football without a whole lot of bitching, and the ball often seems to take a strange course when I’ve kicked it.

There was a time when I couldn’t play for a long while. It looked like I was ready to go (Death! There she is again.) It’s an illness that can rear its head at any time, it might return in twenty years, it might stay away forever, no one can say. Five weeks after the operation I was playing with the boys again. I shot two goals immediately. Me, who usually never scores, at most ten times a year. Could it be that God exists? That’s what I thought. That’s how simple it is. There’s nothing more to need. And who did I have to thank? Art. That first game, the morning after breakfast in Germany.