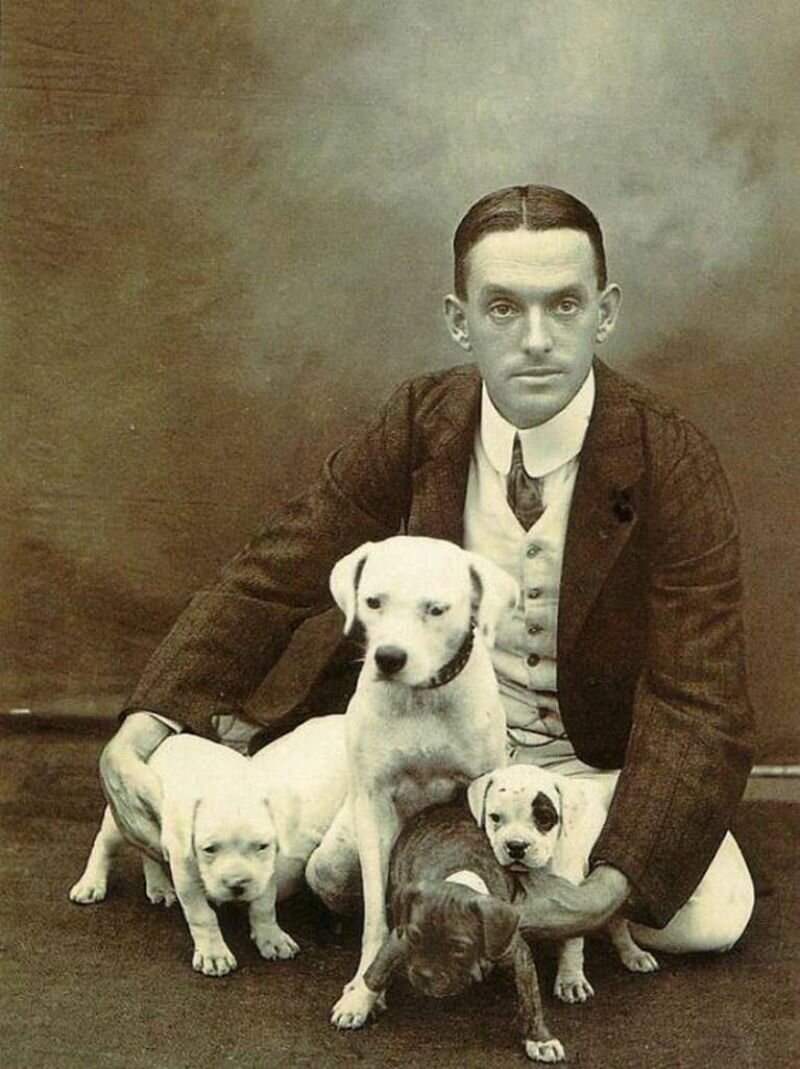

Have you ever wondered what goes through a dog’s mind? I know I have, especially for two particular dogs I’ve had in my life. They were my best friends and I will always remember them.

Growing up, I didn’t have any friends and my parents thought it would be a good idea to get a dog for the family. We adopted a nine year old shepherd from the animal shelter named Tosca. This old girl became my best friend. I even like to think she saw herself as my guardian and me as her pup. But seeing her age she only lived for a couple of years. And one day while I was petting her noticed that her nipples were bleeding. I ran upstairs to tell my mother, she said we had to go the veterinarian to check her out. Her voice sounded reassuring and her facial expression didn’t change, so I thought everything was going to be okay. But I cried all the way to the veterinarian anyway, I was so scared because I knew something was wrong.

My hunch proved true when we arrived. The vet told us she had breast cancer. I remember thinking “that isn’t so bad, cancer can be cured right?” But things wouldn’t be that easy, it would have meant a lot of medical attention and she was already very old. Besides, my parents didn’t have the money or time to take care of her. At that moment I couldn’t comprehend any of this, I was so angry that they were putting her to sleep.

She was my best friend! They knew that, right? She can’t leave me yet!

That night of one of my dear friends died. I held her andshe licked away my tears comforting me. It should have been the other way around.

Until this day I am still wondering what went through her mind. Did she know she was ill? Did she understand what was happening to her? I blamed myself because I was the one who discovered her bleeding nipples. I thought that if I hadn’t anything she would have lived at least one more day.. Then I would have had the chance to say goodbye to her, to give her the best day of her life.

When she passed away, Tosca left a huge gap. I felt alone again when I came home. I missed her presence. I missed talking to someone. My mom vowed to never take a pet again, she couldn’t take the emotional drain it took to see an animal die. But I just couldn’t handle the silence. The house was so empty without her. I started looking around for a new dog, a new friend. I convinced my parents and I found a program that transfers stray dogs from Spain to the Netherlands. That’s where I saw Jimmy.

Everything you can think of was arranged by the organisation, his passport, flight, vaccines, you name it. I only had to pick him up from the airport and pay of course. When the moment was there, my mom and I drove to the Airport Schiphol and awaited him. I was so anxious and nervous. “What if he doesn’t like me, of what if I don’t like him!?” I even had nightmares about it. My mom assured me it would be fine, and gave me a bag of treats that I could give to him. We went to the assigned gate and saw more people waiting for their adopted pets. I panicked and didn’t want people to take my future friend so I made sign with his name on it. Nothing could go wrong now.

I kept wondering what kind of dog he was and if we could get along well. The first thing I knew for sure was that Jim was really good at giving paws. It was the first thing he did after he got out of the cage. I gave him a treat every time he did. But he kept doing it, so I ended up giving him the whole bag of treats. For me it was love at first sight.

In the end he became my best friend, where I went he went with me. He was the first one I saw in the morning and the last one I said goodnight, we were inseparable. He was just nine months old when I got him and I taught him everything I could teach him on my own. He understood me like no one else could and I loved him. But I grew older, made friends, started dating, got a job and started studying. I still tried to take care of him the best I could, took him wherever I went if it was possible and my parents would sometimes even look after him. On top of that I started living on my own and it became impossible to take care of him, I felt immense guilt when I left him alone at home and I didn’t have enough time for him anymore.

A couple of months ago, I had to give my best friend away.

He lives with a couple on the countryside now, it sounds ideal but I wonder if he agrees. I will never know if he’s happy there or if he’ll miss me. I threw a goodbye party the day before he got picked up by his new owners. I thought that would make things easier and it would give me a chance to say goodbye. But he had no idea what was happening and just went happily along with it. How do you say goodbye to someone that doesn’t know he’s leaving? Sometimes I wonder how things would have been if I knew what he thought. Did he bother being alone, did he wanted to stay with me? Would he have said goodbye?