All of our digital media leaves behind traces. But these are hidden traces that are present as invisible abstractions. These traces exist as digital binary structures of code that represent digital pictures, video, texts, three dimensional objects and more.

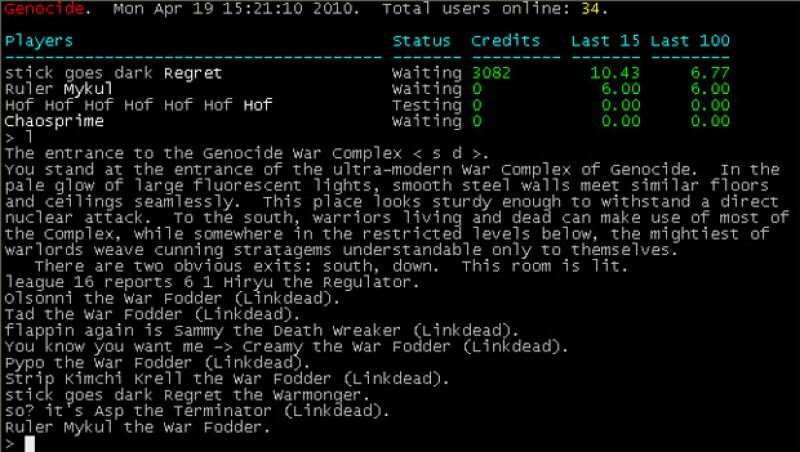

We leave behind cookies on our computers, we store most of our data in a cloud, but we also leave traces on each device that contains digital memory on its hard disk or flash memory. But these traces are invisible: we cannot perceive them as they are, we cannot perceive them directly.

The code’s structure does not readily yield the subject of what it represents. We can’t even perceive the structure unmediated, because we need a visualisation device. We might be able to directly perceive the physical presence of a small disc or a chip from our digital media device. But in the end the digital empire is only about what it represents: the functionalities, the images, the characters and combinations that form a coded language that, in turn, create the language we are able to understand.

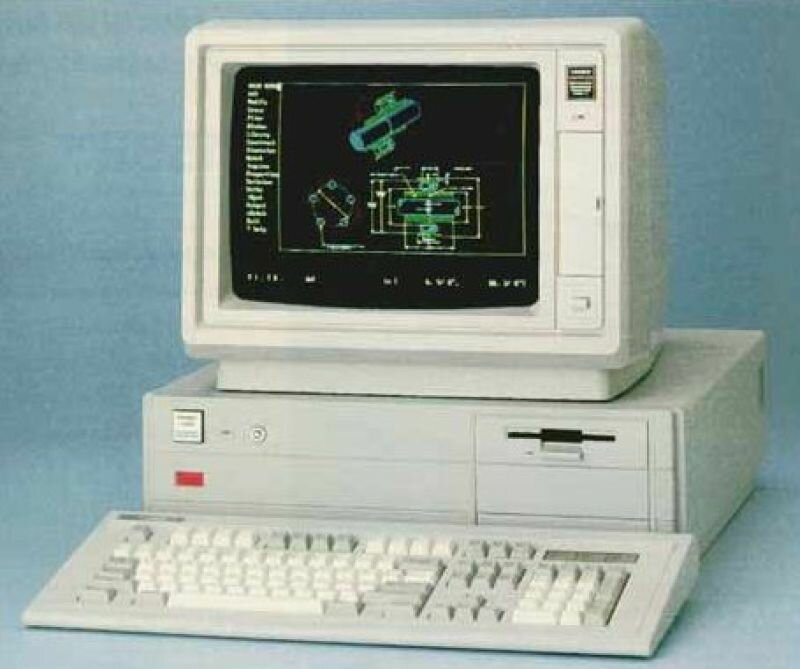

Once I had the problem that I deleted the majority of my pictures, in a state of fatigue, from my hard drive. The first thing I did was google if I could somehow recover this data from my hard disk, despite having deleted it. I learned that a hard disk doesn’t actually physically delete your data, but reassigns the specific space that was used for the data, to be free to be overwritten.

This meant that the data was still there, but that the doors that lead to the used space on my hard disk where the images were housed had a little note on them saying that they were free to be taken up by new data. So, there’s a time between the reassignment of the digital space and the replacement with new data, which is a kind of no man’s land.

We are living in a less direct material world and a more digitalised one, where traces themselves seem to be a disappearing thing. Where we easily replace the old in order to maintain the clean and the new. The moment we throw something away, we also throw its trace away.

Maybe it’s time to become more materialised again. To be attuned to a greater sense of the things around us that we like to touch, feel and smell, in addition to the digital form of matter we indulge ourselves in. This must not be seen as a critique on our contemporary digital information- and imagery systems, but more as an essay to think about the value of the things we can see with our naked eyes, with our bare hands, our open nostrils, and our own ears.