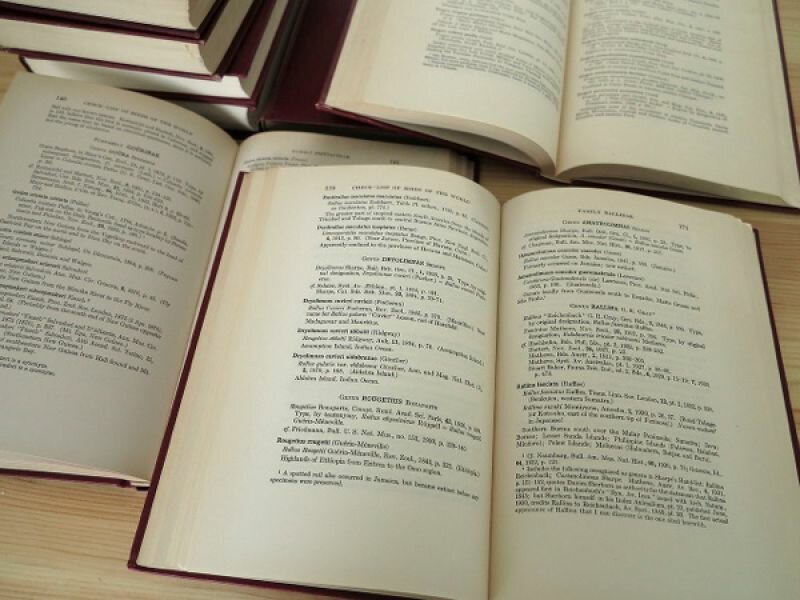

“Wilmering's favourite ornithological book is Check-list of Birds of the World by James Lee Peters (1889-1952). It consists of no fewer than 16 hefty volumes, the last of which appeared in 1987. After the author's death, fellow ornithologists completed his life's work. Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this book is the fact that the checklist is no more than the title suggests: an endless list of bird names, systematically arranged according to class, order, genus, family and species. It is not the type of book one would expect to find in the bookcase of an artist, for the simple reason that there are no illustrations. It is a work by and for the scientist who has already done his field work. Identification is followed by ordination, classification and taxonomy. Observation by registration, tables, and diagrams. A bird is best 'read' in letters and numbers, a fact that was clear to Carolus Linnaeus back in the mid-18th century. In designing his Systema Natura, he gave both plants and animals double Latin names, again without benefit of illustrations. While the new system was a boon to scientists and collectors, the average fancier who had to rely on a Latin text would have been at pains to identify the bird that just landed on a nearby branch.

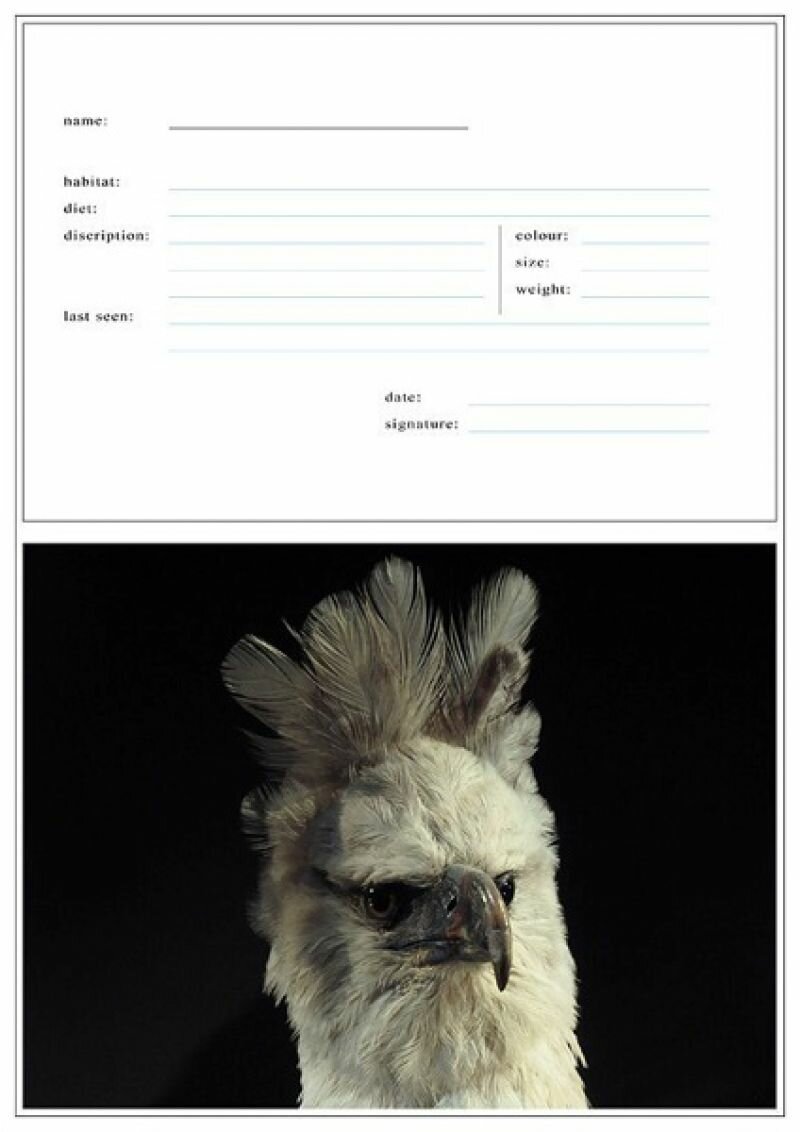

Few artists had mastered the true-to-life illustration of nature, and one wonders if people actually believed what they were seeing. Nature is of such overwhelming beauty that it is sometimes hard to believe that it is real. When in 1719 Louis Renard published his book on the fish, lobsters and crabs of Ambon, he came in for considerable criticism. No one believed in the existence of such "candy canes with fins": surely those shocking pink creatures were a figment of the artist's imagination! But by the time the second edition appeared in 1754, the publisher had rounded up several eyewitnesses who attested to the authenticity of the illustrations. One of them was Aernout Vosmaer, director of the menagerie and zoological cabinet of Stadholder William V. He assured the doubters that the astonishing shapes and colours of those tropical fish and crustaceans were indeed true to life. But the illustration of a mermaid no doubt led many readers to view the book with a critical eye. Such mythical creatures were ultimately discredited by the new classification system devised by Linnaeus. Henceforth encyclopaedic works devoted to natural history no longer included illustrations of griffins, eight-headed monsters, and fishtails sewn onto shaved monkey torsos. In the 17th century books were still being published which included the harpy, an unsavoury creature with the head of an old woman, sharp claws and a filthy torso. Until empirical research ultimately proved that no one had ever seen a harpy nest. For centuries, bats were also regarded as birds, since they had wings but no feet. Thanks to Linnaeus, they later winged their way into the world of mammals.

In the end, scientists could not do without serious artists. Between 1750 and 1850, thousands of illustrated volumes saw the light of day, in the belief that nature in its entirety could be committed to paper. This led to a host of megalomaniacal projects, which foundered due to their striving for completeness. By the time a register was completed, there were already hundreds of new sorts awaiting publication: the seas proved inexhaustible, the forests unfathomable. But then came the solution: specialization. The striving was no longer to include all the birds in the world, but only those found in India, say, in the southern foothills of the Himalayas, and preferably only the parakeets native to that area. Years ago, I purchased just such a book.

One of the most beautiful bird books in the world comes very close to Wilmering's bird installation, in which the birds are served up by the hunter, the gastronomist, the scientist and the artist. It is The Birds of America (1827-1838) by John James Audubon: the authoritative five-volume bird book in which 443 North American species are described and portrayed life-size. Today it is the world's most expensive book. For days, Audubon would conceal himself in the undergrowth, observing the birds and taking meticulous notes on how they flew, how they mated, and how they fed their young. This was inevitably followed by the aiming of a gun and the pulling of a trigger. For Audubon the hunter, it was a unique experience to feel the body while it was still warm, to observe it at close quarters, and to add to his drawing the most minute details of beak, feet, toes and the inner side of the wings. He used wires to bend the birds into natural poses, while a grid served as the background, ensuring that the animal was drawn in the correct proportions. This method was later borrowed by the photographer Eadward Muybridge for his photo studies of people and animals in motion. Here we see the real Audubon at work. No doubt he lit a fire that same evening and, after grilling the plucked coot or wood stork, dined on his specimens. Many of these descriptions are accompanied by culinary tips: the yellow-billed cuckoo, for example, is at its most flavourful in the autumn, while the American scarlet rosefinch tastes like any other small bird. It is thanks to his direct contact with the dying animals that he is able to immerse himself in his models. He is the anatomist who dissects carcasses with his own teeth. Audubon was an empirical researcher who wound silver wire around a bird's leg, and a year later confirmed that some birds return to the spot where they emerged from the egg...”