JUST CALL ME DAD

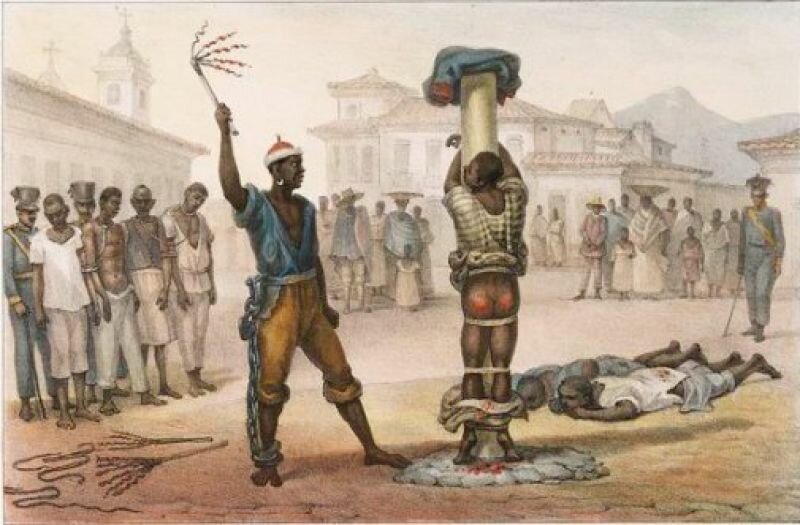

Rush’s seminal opus, Medical Inquiries and Observations, Upon the Diseases of the Mind nowreads like a primer for psychological torture. Suggested punishments for the misbehavior of mentally ill patients include tranquilization through the imposition of physical restraints; food modification or deprivation; cold water treatments; and prolonged shower baths.

“If all these modes of punishment should fail of their intended effects, it will be proper to resort to fear of death.”

FROM CHAPTER VI, TREATMENTS

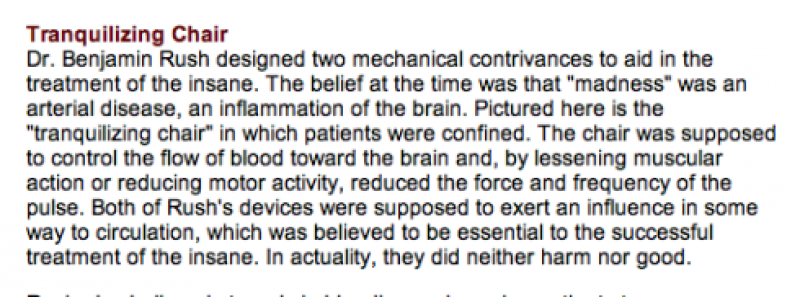

In many cases, the line between punishments and treatments is quite flexible within the medical philosophy of Dr. Rush. Thus the tranquilizer performs a highly useful secondary role in facilitating the application of other treatments:

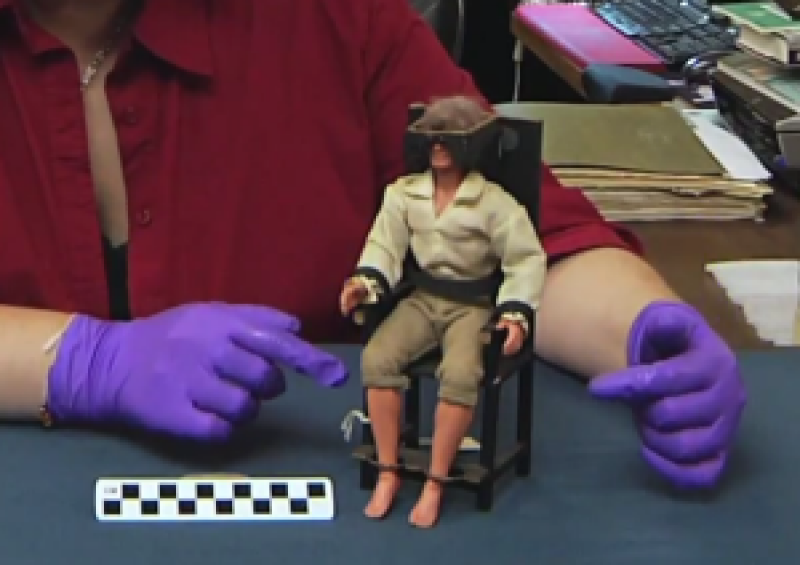

“The tranquilizer [chair] has several advantages over the strait waistcoat or madshirt. It opposes the impetus of the blood towards the brain, it lessens muscular action every where, it reduces the force and frequency of the pulse, it favours the application of cold water and ice to the head, and warm water to the feet, both of which I shall say are excellent remedies in this disease; it enables the physician to feel the pulse and to bleed without any trouble, or altering the erect position of the patient’s body; and lastly, it relieves him, by means of a close stool, half filled with water, over which he constantly sits, from the foetor and filth of his alvine evacuations.”

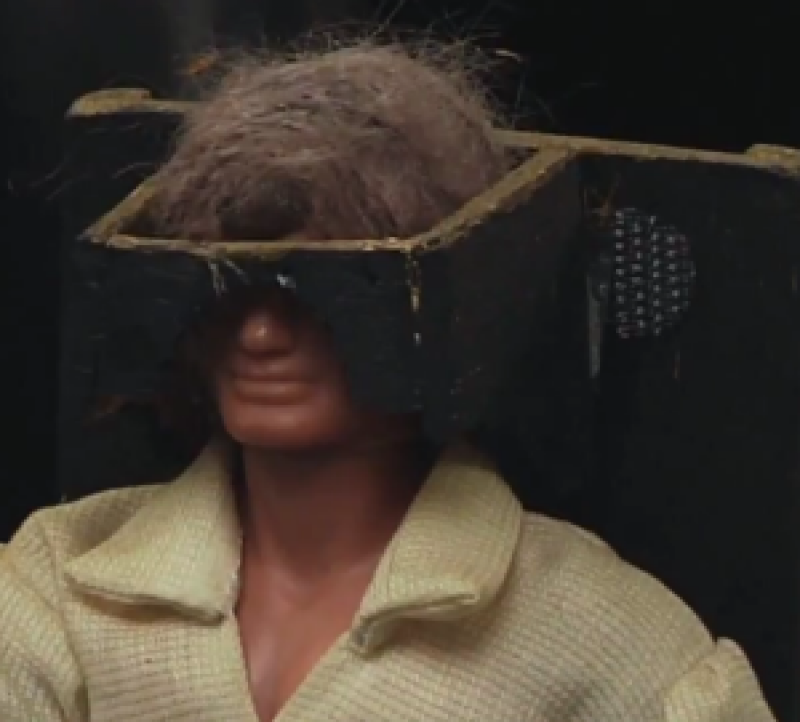

DISPLAY MODIFICATION

Of particular note is the absence of the “close stool”; and the innovation, apparently devised by the model maker, of the blinders. With this modification in place, the patient can neither move his head nor bear visual witness to anything happening within his environs.

NO TOUCH TORTURE

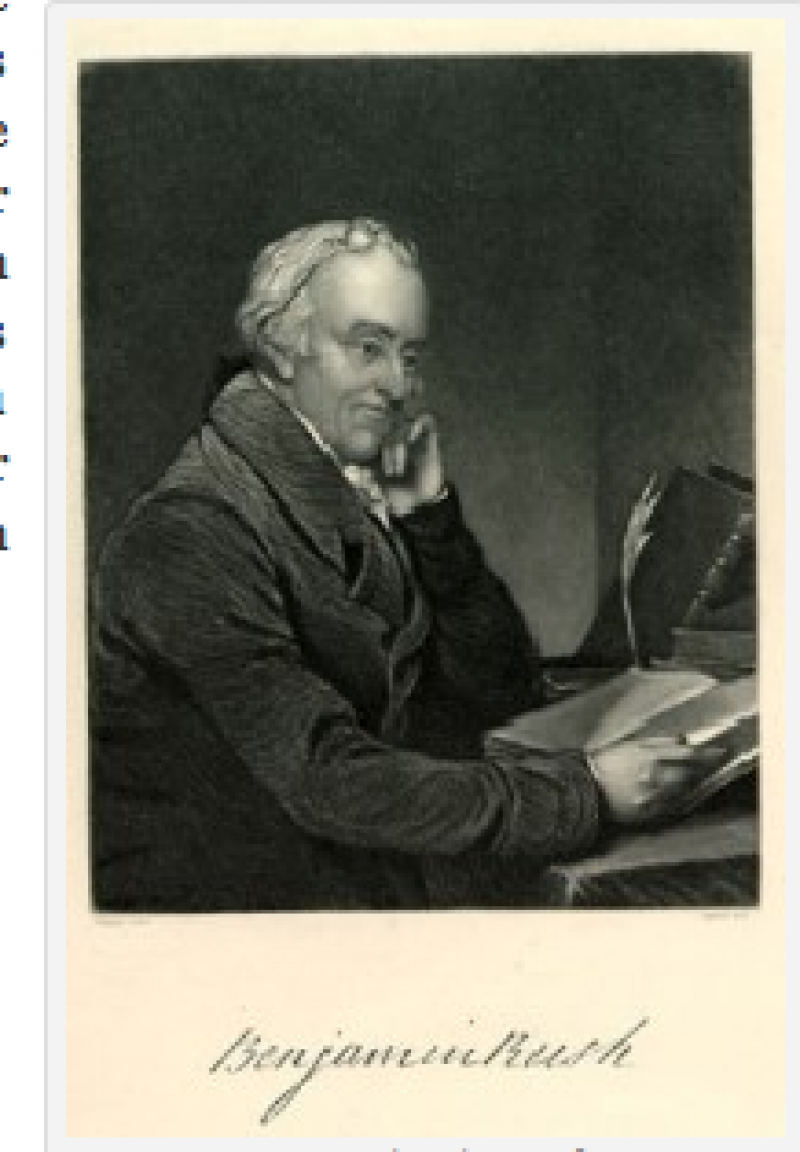

Interestingly, the two most recent recipients of the APA’s Benjamin Rush award, together with the titles of their lectures, are:

2008

Mark S. Micale, Ph.D., Associate Professor, History of Science and Medicine at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.Psychological Trauma and the Lessons of History.

2011

Andrea Tone, Ph.D., Professor and Canada Research Chair in the Social History of Medicine, McGill University. Spies and Lies: Cold War Psychiatry and the CIA.