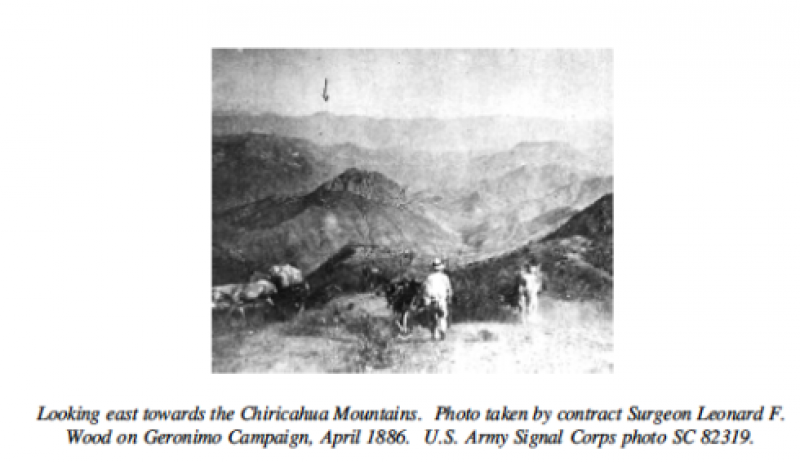

In pursuit of the wily Geronimo and his small band of Chiricahua Apache, General Nelson Miles suffered from a lack of high quality intelligence regarding the movement of hostiles through his geographically complex theater of operations. Chiricahua knowledge of the terrain combined with their high levels of skill in evasion made “hunt and kill” tactics difficult if not impossible to apply, and intelligence gathered by scouts (some of whom were Apache themselves) proved inadequate to the task, or unreliable.

If he was to succeed where General Crook had failed, Miles would need to see and anticipate enemy motion with greater precision and with a perspective as sweeping as the landscape. Thus he set out to establish a regional system of aerial reconnaissance, accomplished by means of the solar-powered heliograph or “sun telegraph”: The signal detachments will be placed upon the highest peaks and prominent lookouts to discover any movements of Indians and to transmit messages between the different camps.

According to a newspaper account written by former signal operator William Niefert:

From the peak in that clear atmosphere we had an interesting view that covered many miles, even beyond the International Border. Nogales 50 miles away, was plainly visible, and away to the eastward one could see a surprisingly distance. The heliograph, or “sun-telegraph” as it was often spoken of on the frontier, is an instrument for signalling by sunlight reflected from a mirror. Metallic mirrors were originally used, but in service, they were hard to keep bright, and hard to replace if broken in the field. Consequently glass mirrors were adopted and much successful work was accomplished by using this method of signalling. We used two 5-inch mirrors, mounted on heavy wooden posts, that were firmly set between the rocks. Vertical and horizontal tangent screws are attached to the mirrors by which they can be turned to face any desired direction and keep the mirrors in correct position with the sun’s movement. As the flash increases about 45 times to a mile, it could be read with the naked eye for at least fifty miles.

Equipped with a powerful telescope and field glasses, we made frequent observations of the surrounding country so that any moving body of troops, or other men, as well as any unusual smoke or dust, might be detected and at once reported by flashing to Headquarters. Troops in the field carried portable heliograph sets that were operated by specially trained and detailed soldiers, by this means communicating through the mountain stations with Headquarters.

For all the effort invested, there is little evidence that any of the information gathered and relayed by the heliographs had any direct result on Geronimo’s capture, which was eventually secured by boots on the ground; boots under the command of Lieut. Charles A. Gatewood, a man Geronimo knew and respected as a brave adversary. General Miles traveled to Skeleton Canyon for the official surrender on September 4, 1886.

The most significant lessons of the Apache Wars had more to do with physical fitness and tactical preparation than with theater intelligence. Counterinsurgency concepts such as flexible response, quick reaction with emphasis on mobility, body counts and small unit actions were all conceived and refined during the Apache campaign, from tactical necessities dictated by both the harsh terrain and by the character of the enemy. For aerial reconnaissance to be effective in the context of counterinsurgency, there must be a more rapid and dynamic relationship between intelligence and the delivery of force. The heliograph system of General Miles had far too many dots (and dashes) to connect: from binoculars into code; then from code to mirror communication; then from decoding to command; and then from command to the pursuit force, via the same cumbersome circuitry. Radio would of course eventually significantly reduce these gaps, but the most pure expression of Shock & Awe would not be achieved until intelligence itself became weaponized, in the form of Predator drones.

The capture of Geronimo resulted in the removal of most Chiricahua from the desert landscape that provided the basis for their entire culture; they were placed in rail cars and transported to Florida, into an environment so foreign that it may as well have been Madagascar. Exposure to new diseases compounded by the shock of a climate and landscape antithetical to their culture and experience, many of the captive Chiricahua died within the first year. Such dynamic relationships among intelligence, identification, cryptography, rail transport and death would become more fully articulated in years to come.