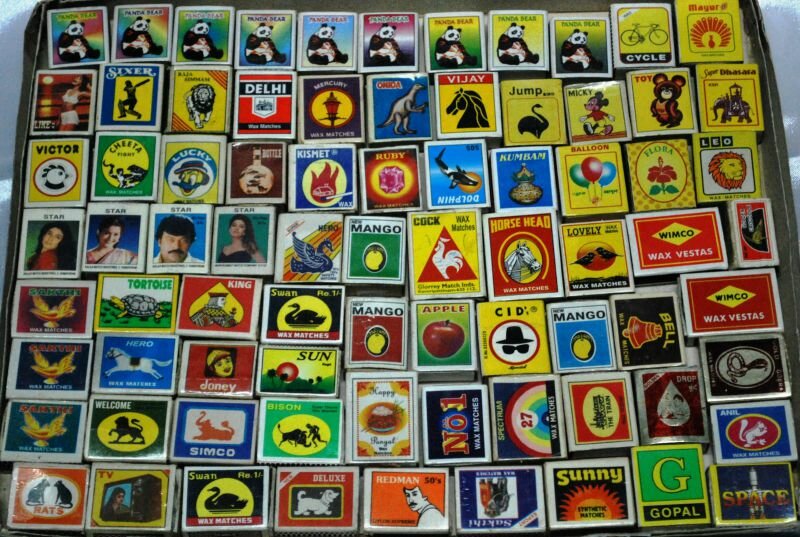

A box of matches is a pocketsize miracle. Destructive force taken hostage in a mass product, tamed nature by the pack. The matchstick, puny as it might be, is a great symbol for the way in which man has forced the elements under his control.

How our ancestors learned to handle fire cannot be said with certainty. It is plausible, however, that it has taken long for early humans to not only transport and maintain fire from a natural source, but to also generate it themselves. Ever since the invention of the matchstick, the art of making fire has become a piece of cake. Never before has fire been so user-friendly and mobile. Moreover, matches were ‘the only manmade objects that were so cheap that you could ask a stranger for one,’ writes sociologist J. Goudsblom in his book Fire and Civilisation.

Numerous scientists and philosophers have dealt with the question as to what distinguishes man from the animals. Some consider the use of language or tools characteristically human acquisitions, but there are plenty of indications that apes and other animals also make tools and master complex systems of communication. According to Goudsblom, the human species has a monopoly for one ability only: the control of fire. Over time, we have come to set the world on fire. On photos taken from space, the nightly earth glows with the domesticated fire of houses, factories, streets and highways.

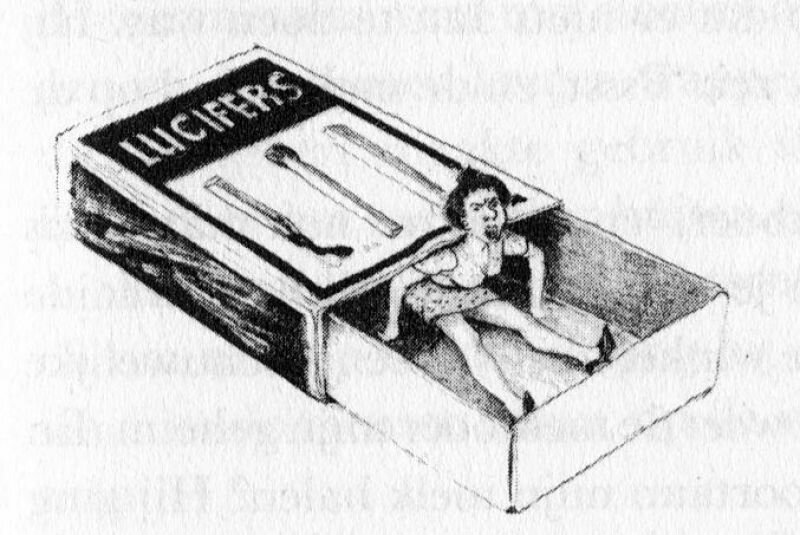

The matchstick has gradually become a nostalgic item. Will enough users remain to prevent their extinction? Surely. There are few things more moving than a box of matches. Like a group of jinn, the unused sticks lay asleep in their carton housing. Each match is a fuse, a chance to get something going. Even if that is merely a passing illusion, as is the case in the story of the girl with the sulphur sticks who, barefoot, sells bundles of matches on new years’ eve. She escapes the cold and hunger by lighting her own unsold merchandise, and experiences a vision with each stricken match until death catches her off guard. Against a single match the darkness flinches is the name of a picture slide installation by media artist Jeanne C. Finley from 1998. Sometimes a title is a work of art in itself.

I used to fantasise once in a while about a trip to a production forest for a matchstick factory. I wanted to walk through trees that would end up as fire sprigs in lightweight boxes, boxes you can shake to hear the sound of wafer-thin promises rattling against each other.

There are two fields in which the matchstick is still valued for its worth. First there is the market of the emergency kit. What if the earth is hit by a nuclear bomb, a natural disaster, a colliding meteorite, causing all electric circuits to fail? Who wants to have a chance at surviving such a catastrophe needs to make fire. Not a single emergency kit, therefore, lacks special supermatchsticks, waterproof and extra thick.

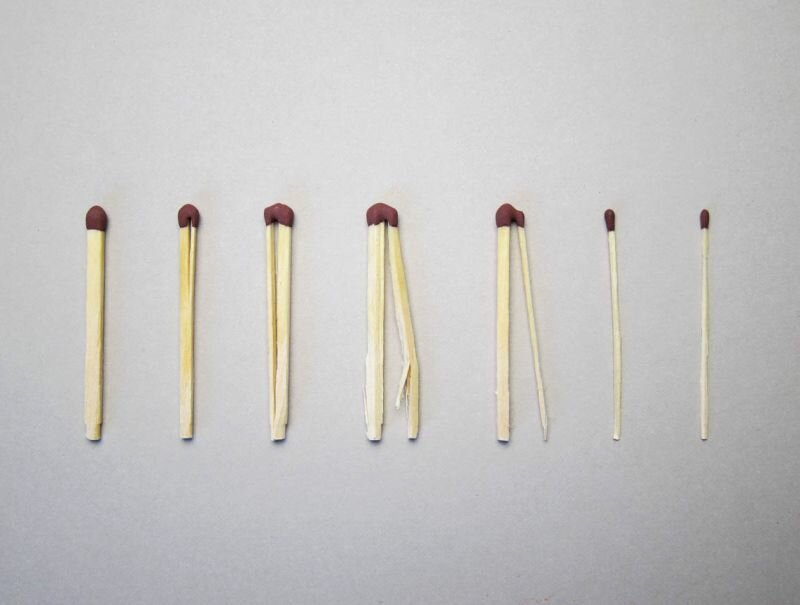

But also for ritual and religious occasions are matches still a precious requisite. Perhaps because they proffer the semblance of timeless naturalness, with their analogous flame and primal scent of fire. Yet the fact that the striking of a match is a modest ritual in itself might also have to do with it, a ritual in which light and warmth emerge at the expense of irreversible destruction. Every match perishes at the hands of its own function after all. That makes the striking of a match a grave moment. No matter how ephemeral or futile, it is a sacrifice. A full-fledged drama of thirty seconds: the preliminaries to the ignition, the promise of combustion, the ineluctable consumption that follows as the fire devours the wood, the catharsis of the freeing of light and heat, the demise when the material has served its turn. But without the end there is no beginning.