The book, Folk Archive, by artists Jeremy Deller (1966) and Alan Kane (1961) is a true feast for the eyes and radiates the pleasure of making. The publication documenting the exhibition on folk art showcases the artists’ love for the phenomenon. Over a period of seven years they collected all they could on “British creativity”. On the BBC’s website, you’ll find a number of video clips in which Jeremy Deller, an attractive young man with long hair, the winner of the 2005 Turner Prize, walks through the exhibition, enthusiastically explaining: “There are two hundred and fifty artworks in this show, and they’re all very different in nature.” He shows a drawing by a prisoner, envelopes for sick notes scrawled daily by a guard who also happens to be an amateur tattoo artist, but also eggs hand painted with eerily realistic clown portraits.

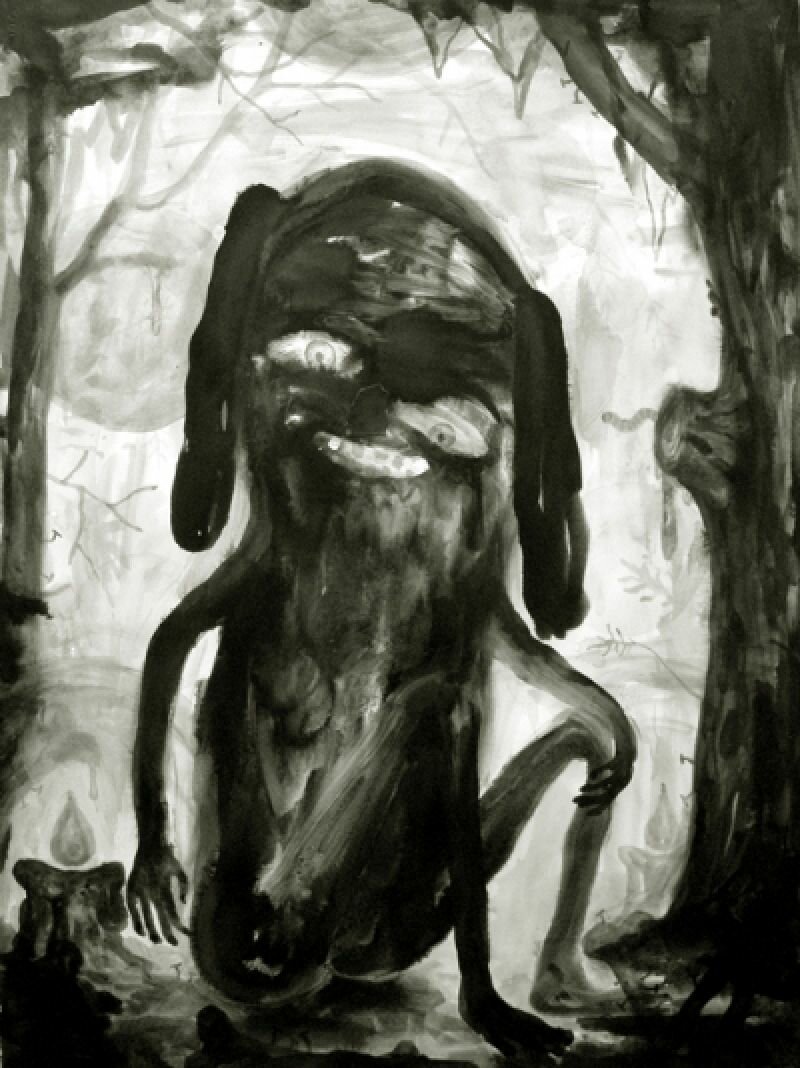

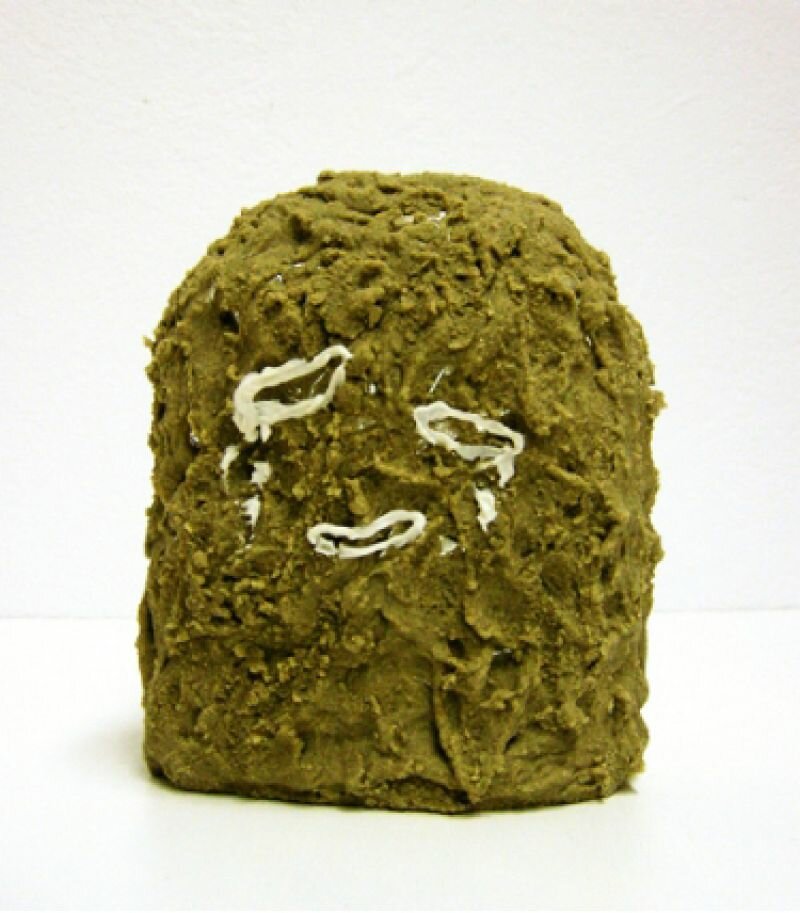

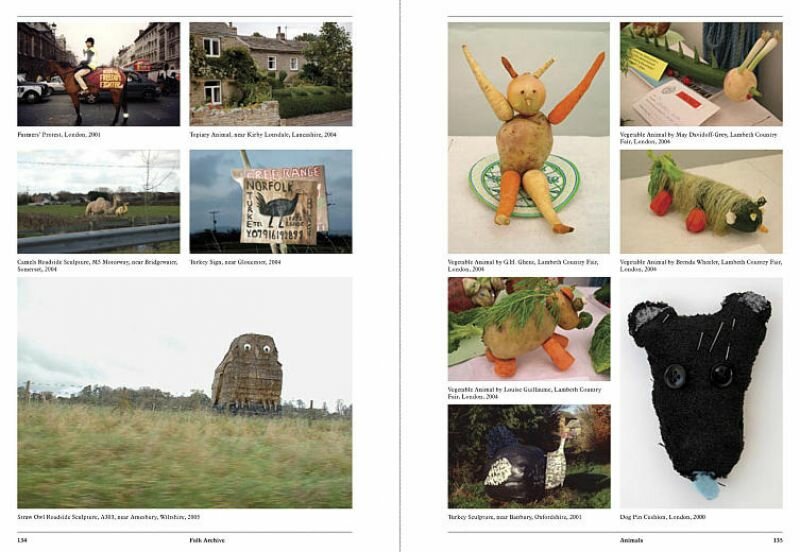

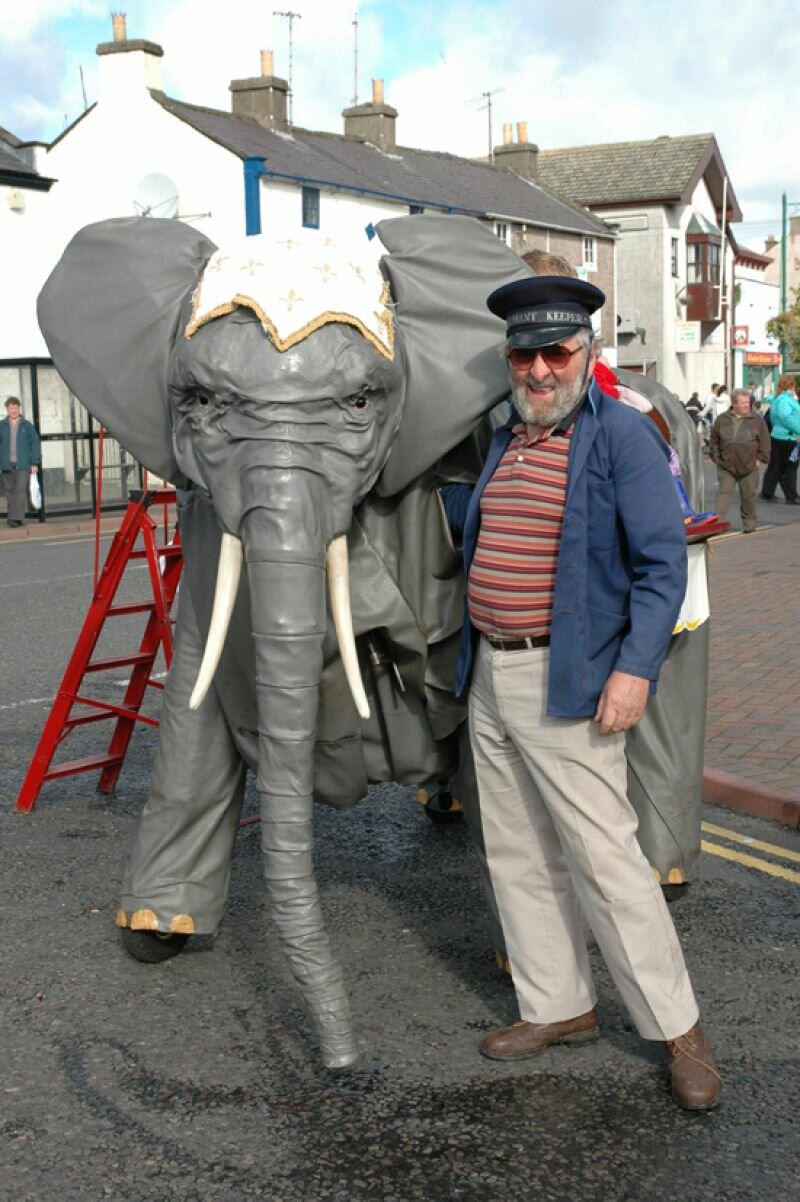

With great pleasure and fervour, Deller and Kane collected a range of anything they could find on the broad topic of “contemporary popular culture.” They took photos and videos , received documentation from others, as well as found historical footage of celebrations that have been part of tradition for centuries, such as the World Championship Silly Faces or the Egremont Crab Fair, a week long festival in Cumbria that occurred in 1387 and included a pipe smoking contest, a vegetable show, and an apple-giving parade. Among the exhibition were objects they collected, like embroidered underwear used at certain festivals for wrestling matches. The last retrospective on British folk art had taken place in Whitechapel, meaning a more modern perspective was very welcome.

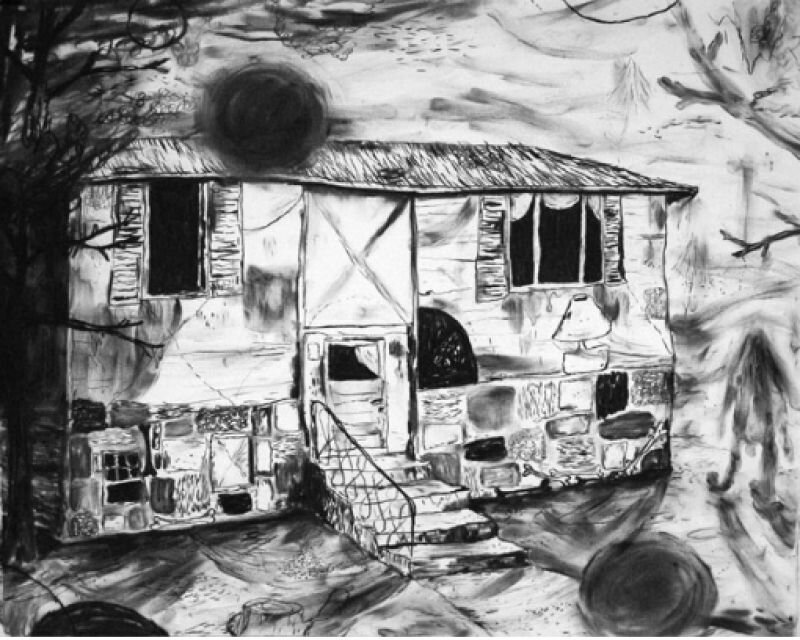

For a year, the Folk Archive exhibition travelled from museum to museum. Luckily, we still have the wonderful catalogue comprising of a colourful collection of photographs, texts, and screenshots. Each time you page through the book, you’ll come across something you hadn’t noticed before: a giant bear made of straw walking through the high street, an old Cambridgeshire custom in which the villagers would be expected to dance for this “bear” on the town square and feed him honey. Or an old forgotten tradition in Blackpool that prompts young girls to dress as old women for a celebration.

The book has been divided into different categories such as performance (like the silly faces competition) but also into politics, life and death, animals. Included are Ed Hall’s beautifully painted signage and banners used by members of the trade unions during demonstrations. The forward begins on the cover, in which Deller and Kane start explaining their methodology: “a personal selection of images and stories that excited or amused us.” They refrain from using the term “outsider art”, a term used profusely in their art world. These artists shift their choice, their archive, from one context to the next, from the street to the museum.

Deller and Kane explain that they were searching for humour, modernity, a new perspective, refreshing directness, and much more: “We find ourselves in an area between art and anthropology. As artists, we’re going on an optimistic journey of personal discovery (often close to home.) As anthropologists, we hope to describe and experience something worth seeing. For those interested in anthropological approach, we must apologise for the term ‘archive’ which is so often misused. Also, we’ll have to apologise for the artistic nonchalance in relation to details. (Artists have been using the term archive left and right recently, it’s a fashionable term that’s sometimes used to describe meagre collections. Archive apparently sounds interesting. To all those involved in folk or regional cultural scenes, we’d likewise like to apologise for that cheap term, ‘folk’ as well as plundering whole worlds.”

Folk Archive is a journey full of surprises through an unfamiliar England.

Folk Archive, Contemporary Popular Art from the UK by Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane (2005).