The Dutch term ambacht originates from the Latin words ambio for ‘around’ and the verb agere for ‘to lead, to bring’, meaning craft or craftsmanship. Originally, it carried the meaning of messenger, herald or servant. Much later, it was no longer used to mean the person who carries out the service, but the service or handwork itself. Craft thereby reveals itself to be primordially related to the execution of practical functions. That is why nowadays, craft is often given the label ‘applied art’, as opposed to free art.

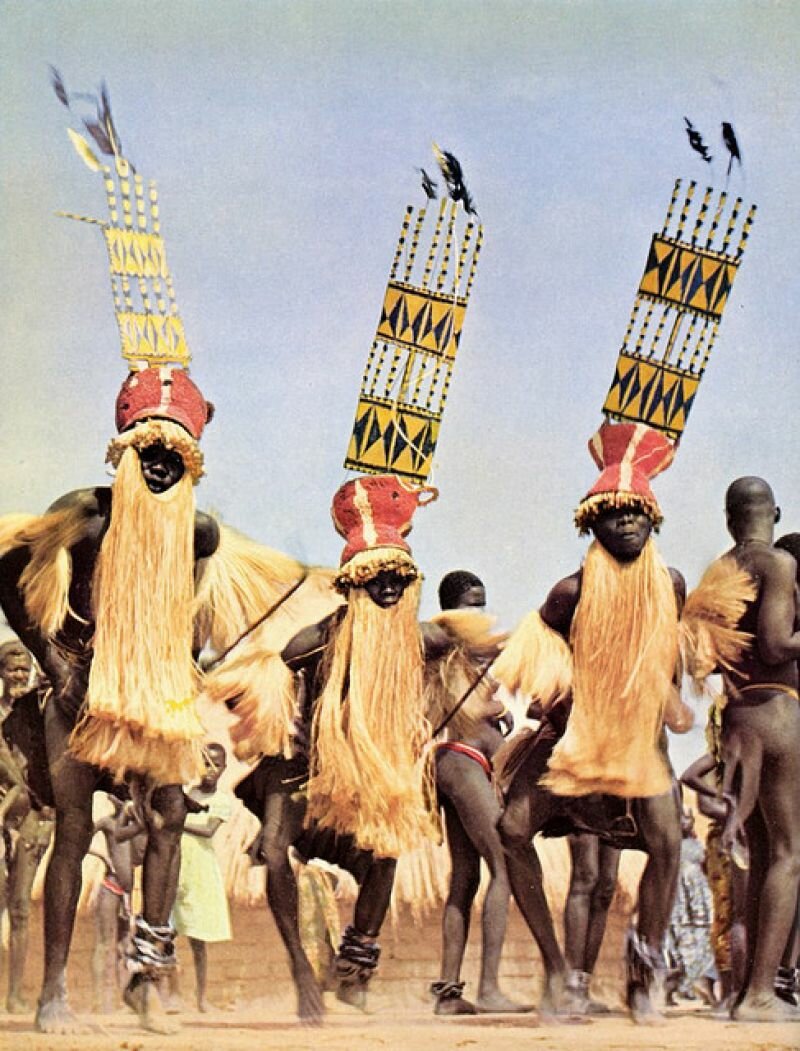

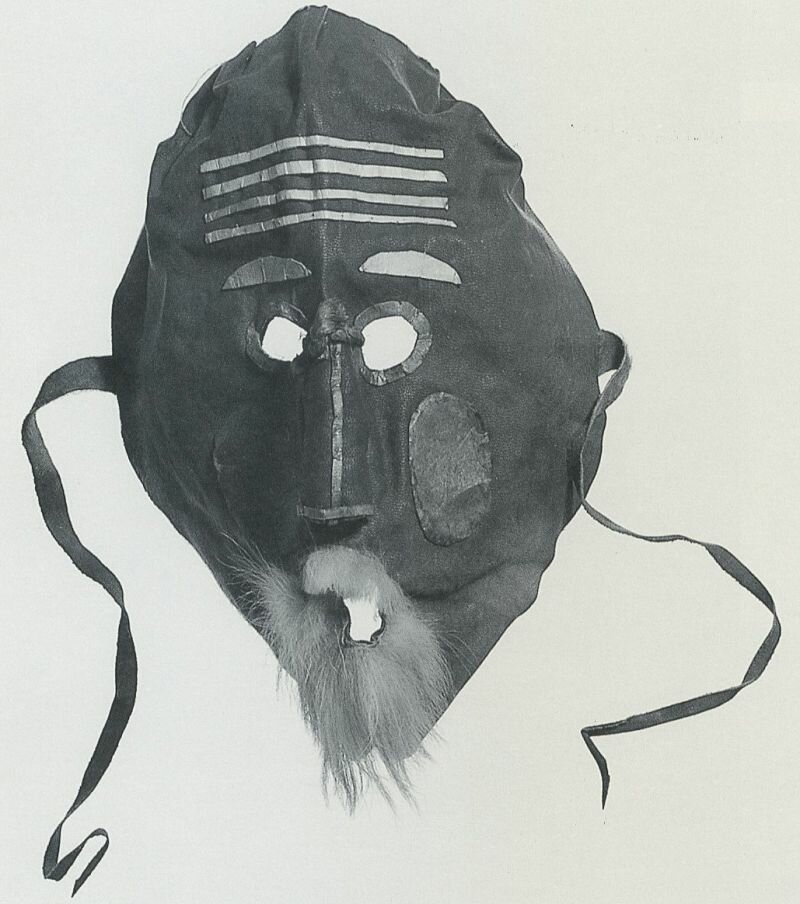

What we can learn from other cultures is that a radical separation between art and craft does not exist everywhere. When a craftsman of the Dogon Tribe in Mali carves a mask out of wood, it is not about whether it turns out to be beautiful or ugly. More important is if the resulting image aligns itself to tradition.

Charioteer of Delphi

Wikipedia

The correctness of a representation is thus superior to the aesthetic experience thereof. Finished masks are kept in places we find irreverent, in dark corners of houses or deserted caves. The masks are reserved for ceremonies and festivities, and are only art objects insofar they are used. Afterwards, they devolve into an insignificant object.

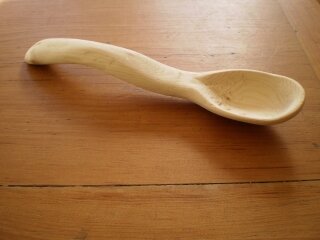

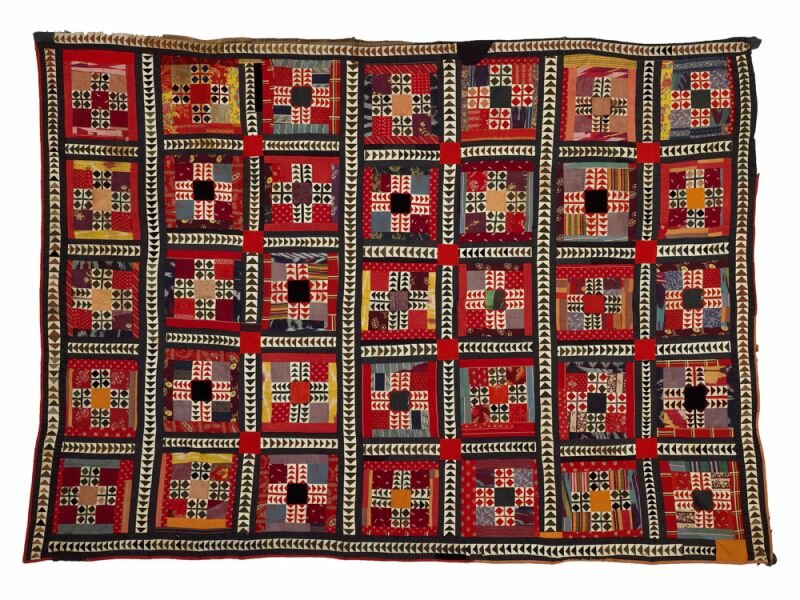

Craft, then, entails animation. An item that has cost hours of work to make becomes valuable by the function that is assigned to it. In the Western context, however, the beauty of craft lies in the many hours invested in the making. But what a man can make, can basically also be made by machine. It differs from the mechanically fabricated object in that the human hand bestows it with a soul. Islamic carpet weavers are most aware of this. They attach major importance to the small errors in their carpets – as only God does things perfectly.

‘God’ can here be read as the concept of perfection, as it is also manifest in mass production. Instead of the detachment caused by a lack of understanding as to the origin of a given object, a human glitch draws a thing closer to us. The reverence for products that are perfect in their sameness, makes way for the urge for proximity. We want to grasp objects in their uniqueness.

What I believe to be most important about craftsmanship is that it makes us aware of this animation. Like a mask receives a spirit during a dance, so does spiritedness form the basis of each craftwork. The idea of this primordial leading around is not far away here, namely circumventing the mass production and technical progress and being led to the spirited and more humane world that has slumbered for so long. Leaving aside specific crafts and techniques, understanding this fundamental idea is paramount.

In these simple, handmade objects lies a humanity that has been little visible for a long time. It is this humanity that has been transformed into an aesthetic. Opposed to that is the icy detachment of the machine-made.

I can understand the carpet weavers. Something entirely flawless, made with or without the help of computers and machines, is very hard for me to personally relate to. When I do things by hand and small mistakes occur, (because a colour does not turn out the way I had hoped, for instance) only then does something become real. It is the peculiar fact that something that you’ve made with your own hands can be more magical than something that shows inhuman perfection.