My favourite light is that of big fat fluorescent tubes on the wall or above the table. In fact, my house is hung full of these tubes alternated by a naked bulb here and there. Fluorescent light is great for reading, and it’s magnificent for seeing what’s on your plate while you're eating. I’m not very fond of ambient lighting. However, I’ve noticed that my guests don’t always seem to agree with me, as they often bring me tea lights and candles as gifts. “That cold light, it’s so harsh and uninviting.”

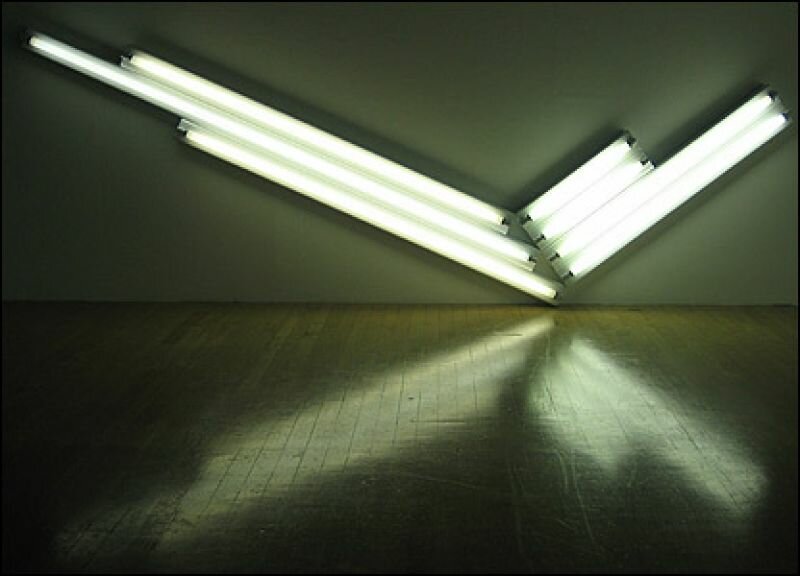

In museums I encountered Flavin’s tubes among the other minimalists: a row of Carl Andre’s bricks or leaden plates laid on the floor, or otherwise Donald Judd’s boxes. I found Flavin’s fluorescents to be rather boring.

During Flavin’s retrospective in Paris in 2006, I experienced what you could call the “epiphany" of the magic of his work. The white rooms in the museum had been transformed into coloured spaces, and in no way did it seem like a cheap Disneyland trick. No, if anything, it reminded me of a holy place, a church, a place of retreat. It was almost as though the rooms had ceased to exist and all that remained was colour and light. As though the walls had fallen away and now served merely as stoppers for the expanding light. I sat silently on a bench, made content and at ease by the display of colour. And like in meditation, my mind began to empty and I did nothing but take in the colour of the dissolved space. Who was this Dan Flavin? I became curious about this man in the same way I would about a suddenly resurfaced long lost relative.

"My name is Dan Flavin. I am thirty-two years old, overweight and underprivileged, a Caucasian in a negro year." This is how he introduces himself in the text in Daylight and Cool White from 1965. He writes of a nasty childhood growing up with two fanatically religious parents. “Before becoming seven, I attempted to run away from home but was apprehended by the fear of the unknown in sunlight just two blocks from our house.” As I read on, I got to know him better.

Although fear was at his heels (revealed in sunlight), these biographical facts are of no importance in understanding his work. Flavin’s work is an endless variation on stuff that can simply be bought in the store. There is no hand of the artist giving form, like in the case of clay or bronze. He chooses, arranges, and makes. As time progresses, his fame grows and he has assistants assemble the works.

His first light works were met with scrutiny, prompting his friends to respond with “you have lost your little magic.” They felt his work was without meaning, a fate that Flavin’s lamps shared with many other Minimal works. How could a collection of stuff, bought from the store, mean anything at all? A row of bricks laid out over the floor seemed too simple to contain any content. Light is full of mysticism and symbolism. For centuries, light suggested holiness, painted in dots and strokes of pigment. In Flavin’s work it simply IS. Light itself is exposed: “blunt in bright repose”, as Flavin himself describes. In presence of light, space is thus transformed into a floating box of colour.

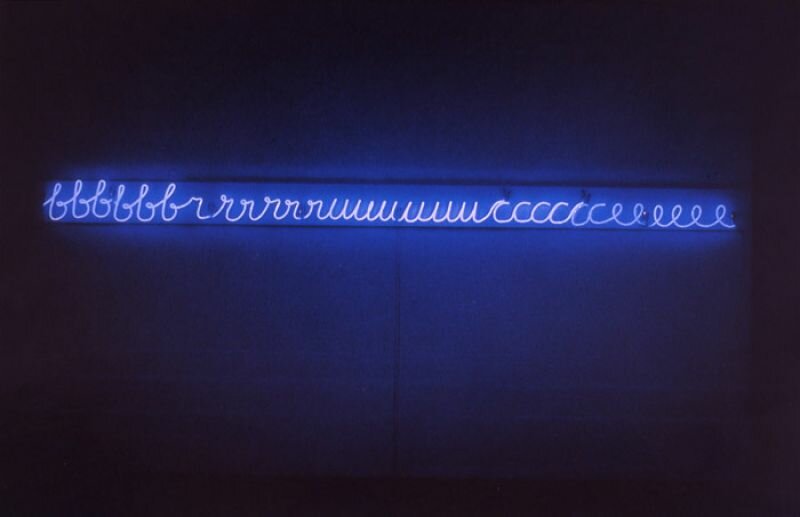

In the catalogue, there is a photo of Flavin’s first pure fluorescent work: a tube curves at a 45 degree angle along the floor and exudes yellow light. A golden aura glitters over the tube and its armature. In a sketch, Flavin titles it The diagonal of personal ecstasy (1963) and dedicates the work to Constantin Brancusi’s infinite column. It’s a strange title. It’s remarkable that Flavin uses the world “ecstasy.” After all, ecstasy or exaltation are not the first words to spring to mind when thinking of minimal art. Minimal art rarely allows itself to be framed within a spiritual context. The objects used by Minimal artists are industrially produced, the core of the work lies in its simplicity, in repetition and objectivity. Simply put: ordinary objects are ordered by placing one after the other, or one next to the other. As a way to discover what the world is like, according to Donald. Judd. For him, it seemed impossible that an expression of feelings could ever be understood by another. After all, could you ever know what my headache feels like? If I look at the colour green, you might just see a completely different colour than I do. Looking at Minimal art tells you nothing of the artist. Instead, its content lies in the viewer’s experience of the work. And that changes with each viewer. Just like each person lives in his own world and experiences everything differently. This could be the message of Minimal art, if it had a meaning at all. “But who could be sure how it would be understood?” Flavin writes.

Minimal art is about repetition, the industrial, the objective. There’s nothing holy or spiritual about stuff from the store. Yet the yellow light is warm and divine.. Like a modern fetish, the ordinary modern tube light casts a golden aura of shimmering, radiating light. And that is precisely what attracted Flavin. His interest was in the effect of the light, at times cold and white, other times an alien green or god-like gold. “Directly, dynamically, dramatically”, is Flavin’s description of the presence of light. An image that, through its brilliance and radiance, betrays its physical presence and flows into the immaterial.

Jan des Bouvries in his monochrome home.

When I return home from Paris, I switch on the television and find myself at a party at the house of the Dutch designer, Jan des Bouvrie. Him and his wife have just remodelled the entire house where everything to the most minute detail is coloured white. The lighting offers the sole ambience. Rooms are lit to green, blue, or white. One of the many examples of how art, falling into the wrong hands, can easily switch to kitsch. “Of course, at night we turn everything red!” his wife Moniek jokes.

*It occurred to me then to compare the new diagonal with Constantin Brancusi's past masterpiece, the Endless Column. That artificial Column was disposed as a regular formal consequence of numerous similar wood wedge-cut segments extended vertically-a hewn sculpture (at its inception). The diagonal in its overt formal simplicity was only the installation of a dimensional or distended luminous line of a standard industrial device. Little artistic craft could be possible.