There are countless bus and tram fanatics in the world: those who know everything there is to know about busses and trams. This is nothing exceptional. However, Robert E. Jowitt’s hobby of photographing these vehicles is an exceptional case thanks to one additional element: woman. Over thirty years ago, the English Robert E. Jowitt chose to completely dedicate himself to his childhood passion of documenting busses, trams, and trolleys. Instead of restricting himself to practicing his beloved hobby during holidays, he decided to chase these vehicles throughout the entire year.

Miniatures like Dinky Toys were of no interest to him and were simply childish reproductions that could never compare to the real thing. He wanted to experience each vehicle in its natural habitat, surrounded by pedestrians, houses, and traffic.

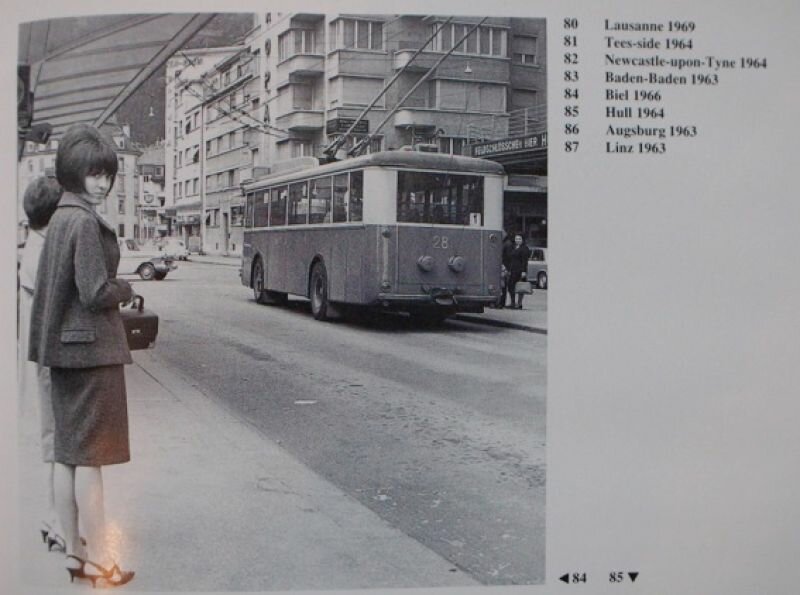

As to be expected, he started taking photos. From Heidelberg to Marseille, from Geneva to Rotterdam, from Munchen to Lissabon. Travelling through Europe, he came across all sorts of old fashioned models still in use. A Carris with wrought iron doors from 1930, a Renault with a curved open balcony from 1935, a Daimler with its small hood from 1950. He not only photographed the busses, but also took notes about their appearance and capacity, the amount of seats and standing places, altered routes, a line whose number was changed—nothing escaped his attention.

Jowitt became the idiot savant of the buses and trams. He wasn’t the only one, and was very aware that he belonged to the legion of bus and tram fanatics. Some of them even knew entire bus schedules by heart. But not one of them created as thorough a documentation of European government vehicles as Jowitt.

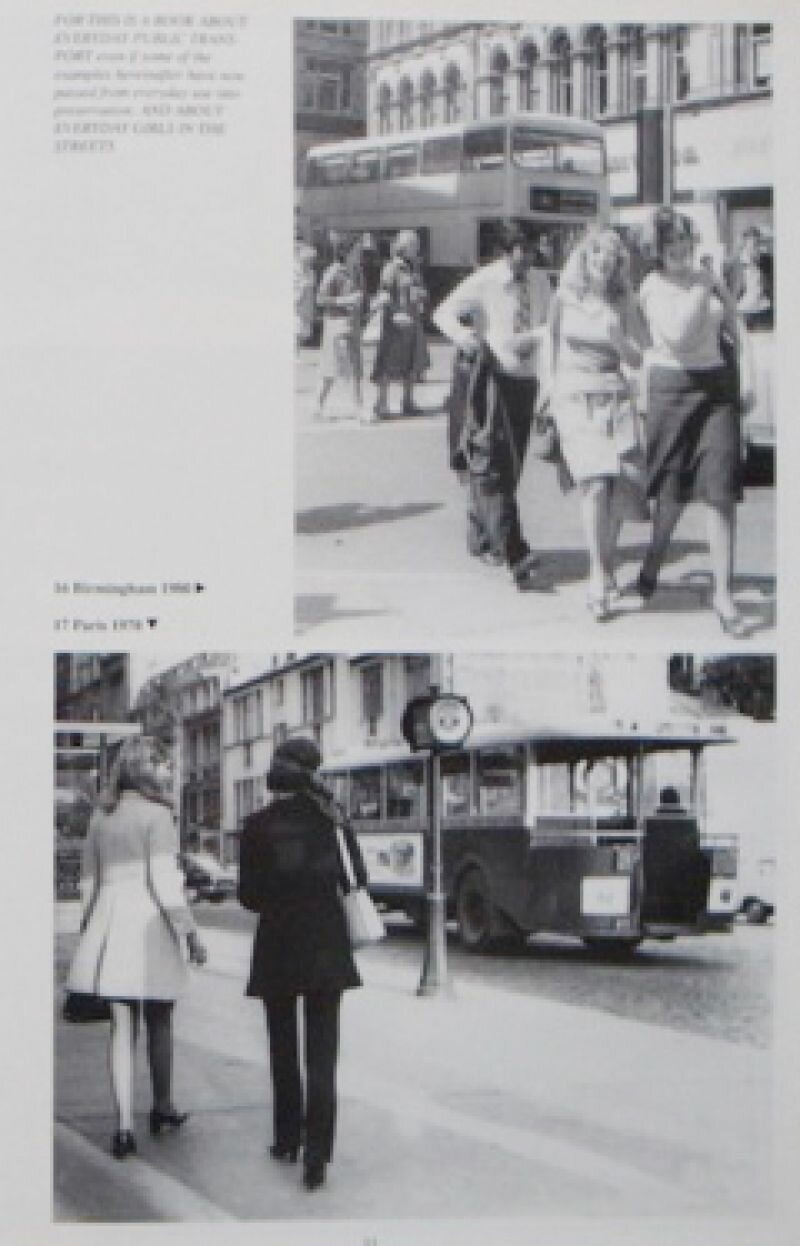

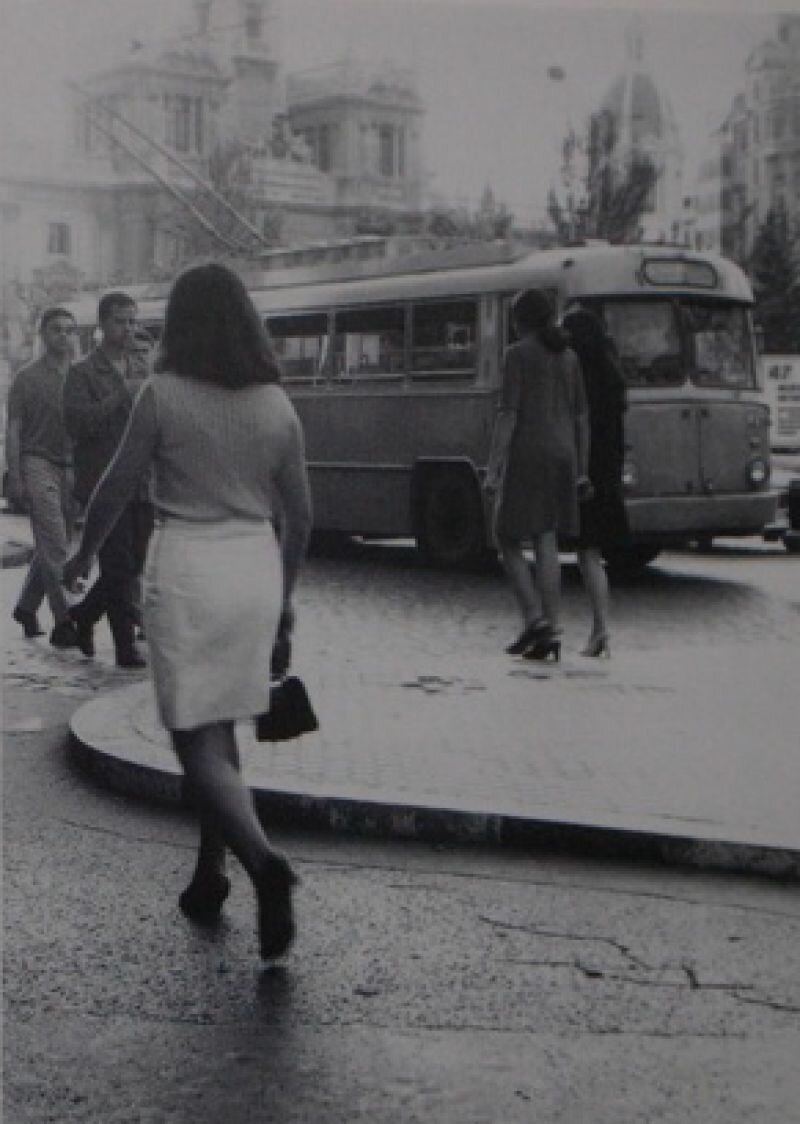

In some photos the bus is little more than a speck in the distance. Other times the glass and metal is shot from close up, like a lover trying to bridge the distance between them. In most photos, the bus is at the heart of the city. No matter how small the bus is depicted, its image is always central within the houses, the buildings, the other traffic, and the pedestrians.

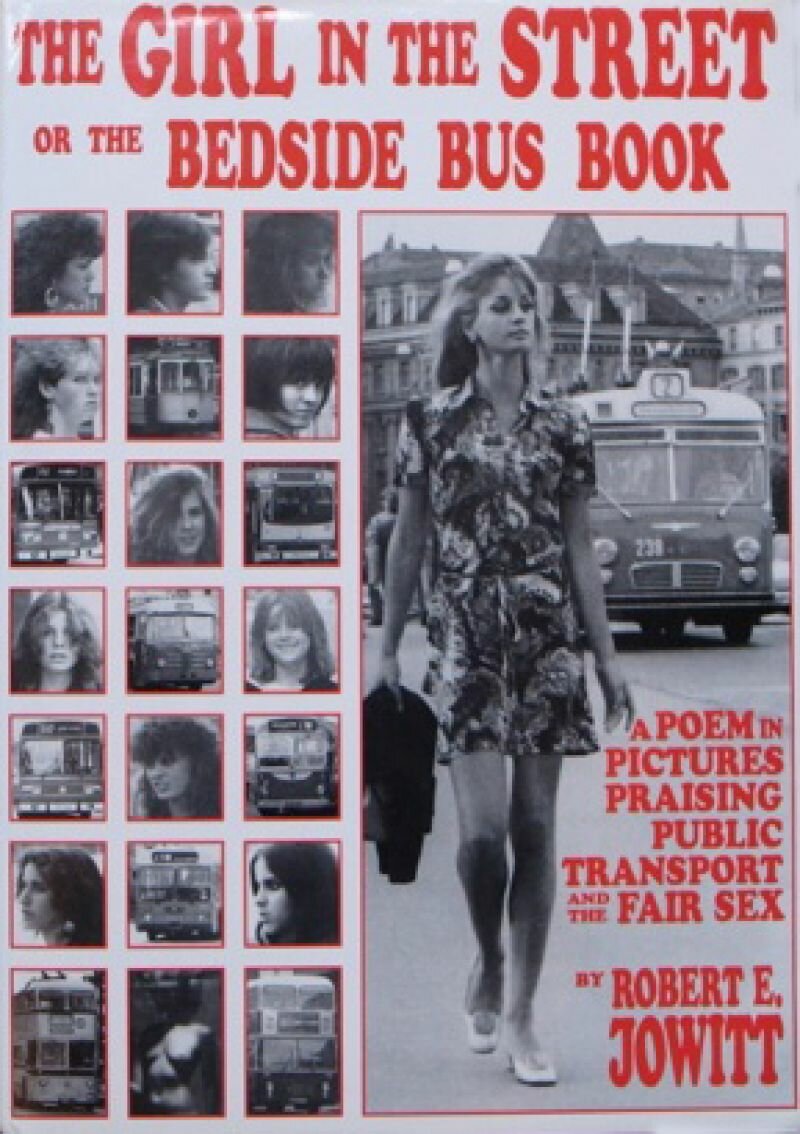

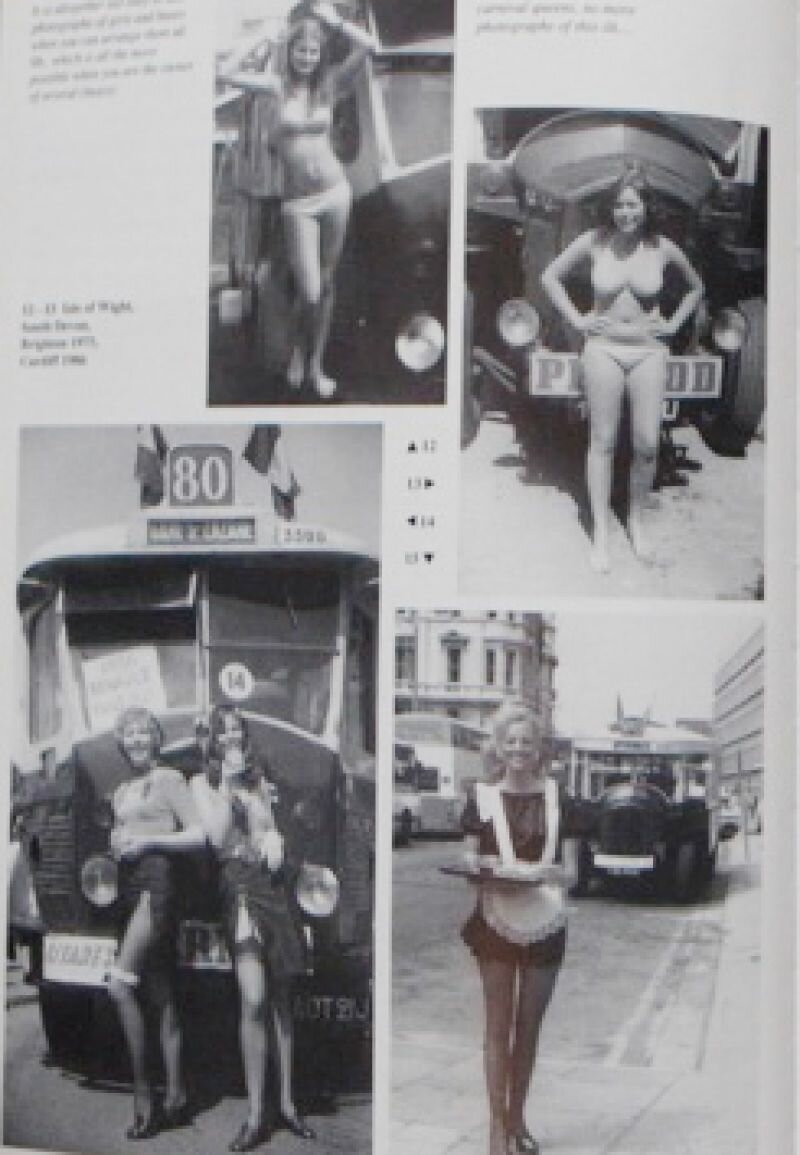

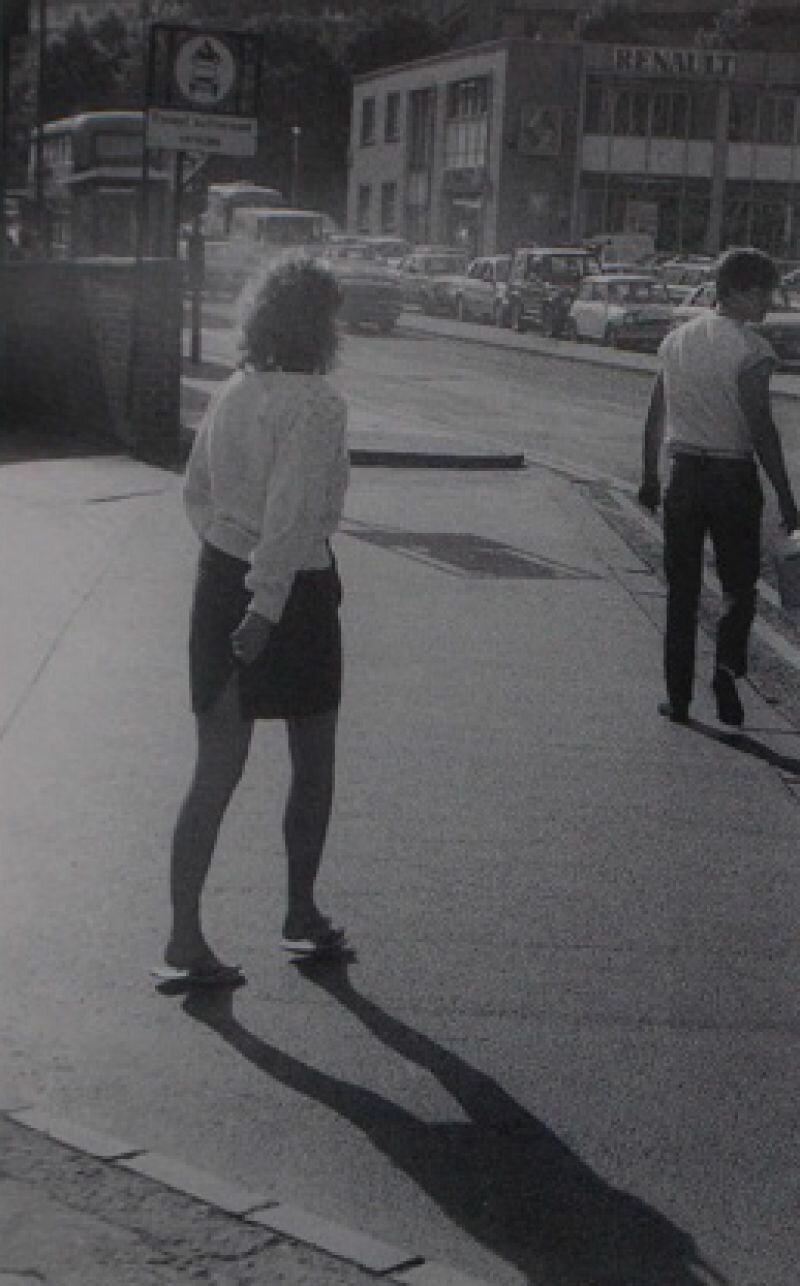

Had he not ventured beyond simply taking endless photos of buses, Jowitt’s collection would have remained typical. The atypical image slowly crept in. Nothing to immediately draw attention. It’s very likely that Jowitt initially didn’t even notice. Had he noticed, the unintentional subject would have gained as much importance as the bus. It becomes clear in the title of the last bus book compiled by the photographer: The Girl in the Street or the Bedside Bus Book. Three hundred and fifty photos lend us an enormous amount of images: sidewalks, street lanterns, shop windows, traffic signs, lawns, terraces, shadows, puddles, and all else you might expect to encounter in the city. But however much the photos differ from one another, there’s one constant: a woman or a girl. She might be sitting in the bus or standing a hundred metres away, she might be walking to the bus, she might not even notice him. Sometimes she takes up the greater part of the photo while the bus is a mere speck, sometimes all we see is her leg peeking out from behind the bus.

Jowitt never strays from this point of departure. The cityscape is only complete when there is a bus and a woaman to be seen. These conditions are so exceptional that the viewer must try his best not to laugh. After all, what logic would decree these conditions to be determining for the completed image of a street or a square?

Jowitt’s answer is simple. While studying a bus in a foreign town, he’d often also be studying the girls passing him by. This made it logical that he gave them, too, a defining place in his photographs.

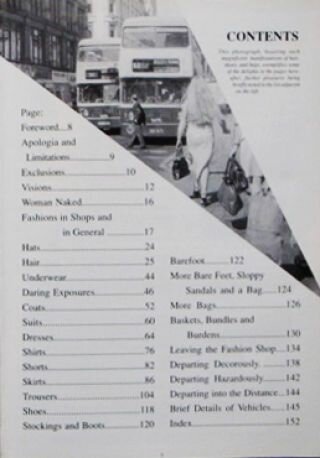

How did Jowitt decide to arrange the photos in his book? He could have placed them in chronological order. Another way would be to arrange them by country or city. But these both seemed too simple. He was especially interested in how time altered designs, and so he placed images from different areas next to one another.

He begins with hair. Short, long, pony tail, plait, henna, tight curls, punk, and of course, the hat. Then clothing, the petticoat, miniskirt, long skirt, and then the more unique varieties. Shoes, bags, piece by piece they appear. He tries to be equally thorough in his descriptions of the girls as with his buses and trams. What was it that caught Jowitt’s attention? An interesting photo, naturally. He also must have thought that his meticulous detailing of the facts would create an exact representation. But it’s exactly this precision that creates a chasm between his words and the image.

Where Jowitt focuses on the hair, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the shoe. In the series where handbags are the focal point, the skirts demand an equal amount of attention. And when it comes to the sleeveless dress it’s the shoes that, once again, lure the eye. As usual, there’s a bus in need of description. Jowitt understands the extent of categorisation his models are subject to. He rarely refers the photographs to one another, but will write “see handbag” or “see bare back” in case it doesn’t fall under one of the carefully chosen categories.

The Girl in the Street will make you smile. It almost seems like an unwitting parody on interpreting photos.

Robert E. Jowitt: The Girl in the Street or the Bedside Bus Book, Peter Wooller, Transport Beaux Arts & Belles Lettres, Walford. Sometimes available on Internet.

This text was published in the NRC Handelsblad on 26-6-1992 and has been re-pubished with permission of the author.