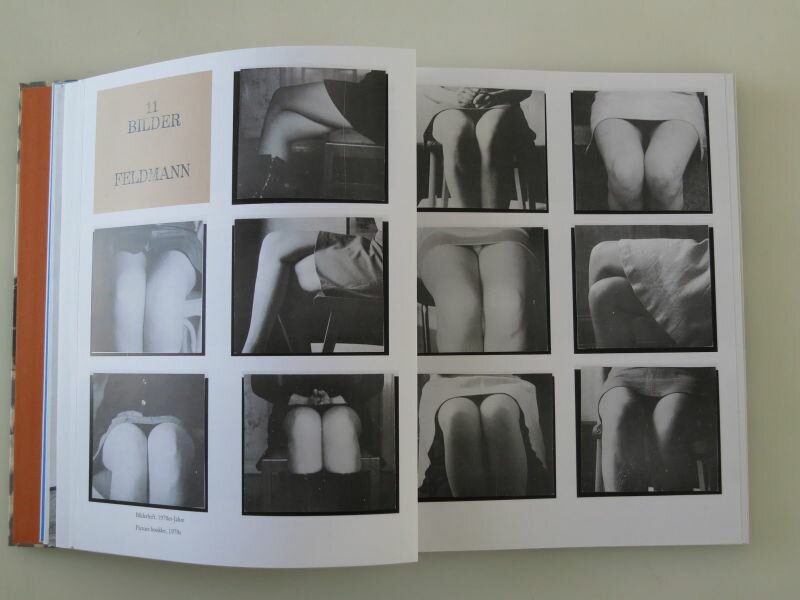

The purchase of my first digital camera meant the sudden end of any inhibitions I still had when it comes to taking pictures. It marked the beginning, however, of my transformation into a full-time Japanese tourist, relentlessly clicking at the sight of anything even remotely close to being interesting. It resulted in an endless amount of photos of endearing kitties in the streets, women with big butts walking ahead of you, of yourself in every setting imaginable in this world, of everybody you have talked to for longer than five minutes and of your own legs on the bed of your hotel room. Suddenly I had a picture of everything. Which, of course, seems very nice, but isn’t.

I remember only taking two 24-shot film rolls with me for a month’s vacation. Was the rice served on our plates in the shape of a little bear worth a picture or not? Now I thoughtlessly take twenty in one go, assuming that the ideal picture will surely be among them in due time. The euphoria of taking as many pictures as you like has long faded now, although I shall never again be able to go back to limited photographing with film rolls, it’s simply too late for that. What I had to figure out, then, was a new way of handling my digital camera.

My first priority was to bring some order into my picture archive, which already consisted of thousands of photos. I decided upon a Flickr account. For all of you who have been living underneath a rock: Flickr is a website on which people manage and share their photo collections, making it also the world’s biggest online photo archive. About five thousand new pictures are uploaded every second and the total amount of photos is estimated at around 300.000.000.

Putting my archive online, thereby making it freely accessible to anyone, even my potential future loved one (you never know), made me look at my pictures critically again, eventually uploading only my best photos. A collection appeared that, with regards to selectivity, equaled the one that would have resulted if I had shot on film.

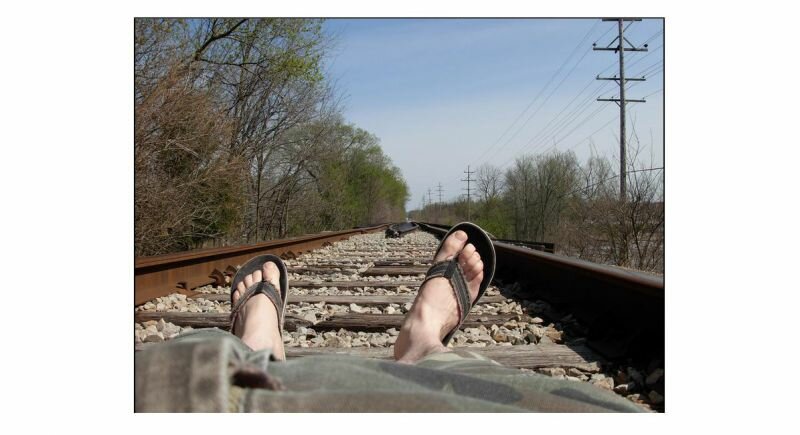

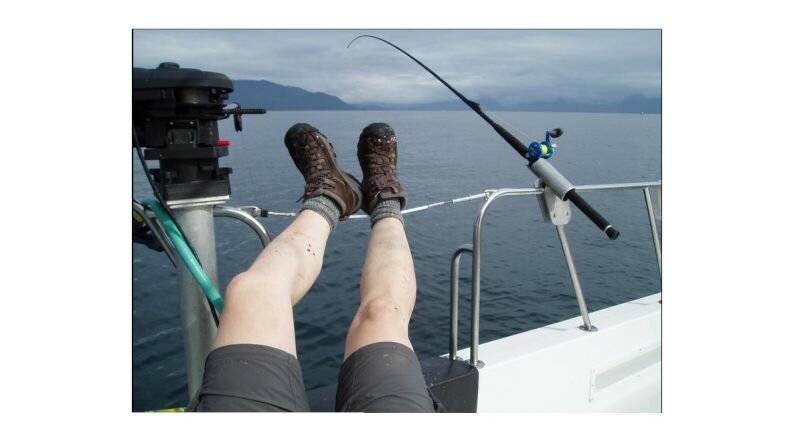

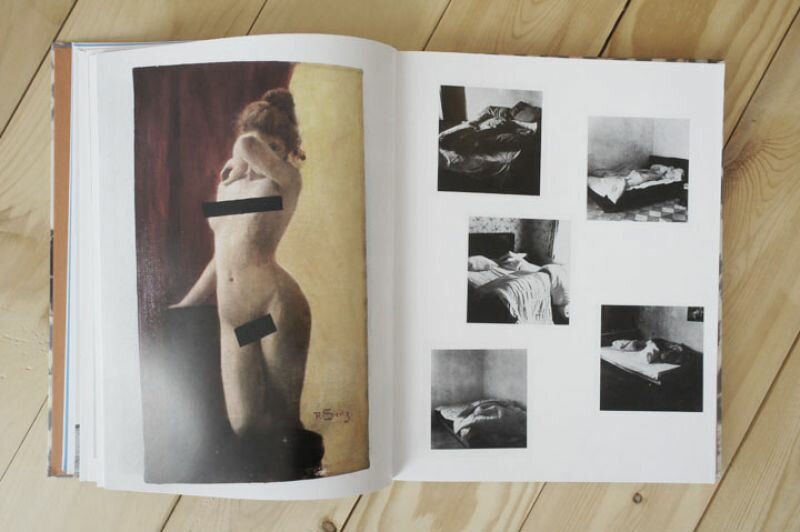

But something else happened as well. Pictures that I had shot out of sheer boredom, such as the photo of my own hairy legs, on a bed with a pink flowered sheets in a sad hotel (in which I stayed all by myself since I had to attend a boring congress in Bergen op Zoom), appeared to have survived the selection process.

It was a picture I would have never shot if it had required any thought, but which I found interesting nevertheless by virtue of the immense sadness that spoke from it.

A couple of days later I received an email. On Flickr there are different groups that gather photos around a theme. I was emailed by the administrator of the group ‘Sitting in my Hotel Room’ asking me if I would add the photo to the group. I took a look first, finding almost two thousand pictures taken by people alone in their hotel rooms. Most of these were very ugly, uninteresting pictures by themselves. For example, some show only a television screen with a painting of a mountain landscape above it, or a view of a city full of skyscrapers, captured from the hotel window. Pictures that look like you have seen them a thousand times before, and many of them are of very poor quality.

Nevertheless, something magical happened when I saw all these photos together. All of a sudden I could see the thousands, millions of people before my eyes who spend every night somewhere in an anonymous hotel, alone in the world except for the company of their digital cameras. By seeing all these photos together the sadness was enormously magnified, for in this photo archive the world seems to contain lonely hotel guests solely. At the same time it consoles: all these people are not alone, but convene on this site.

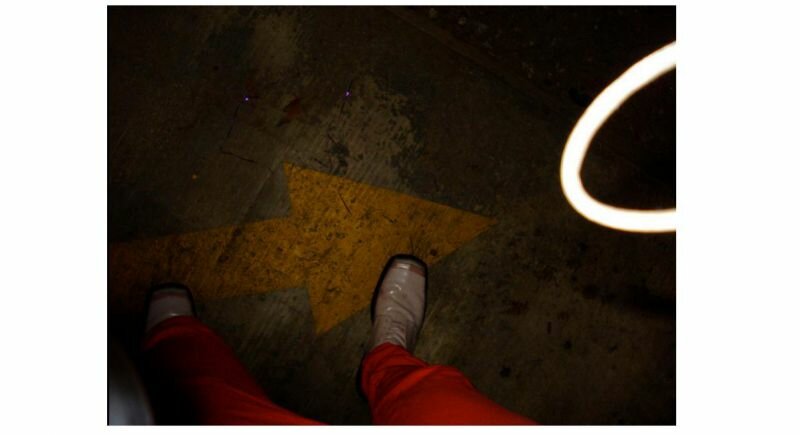

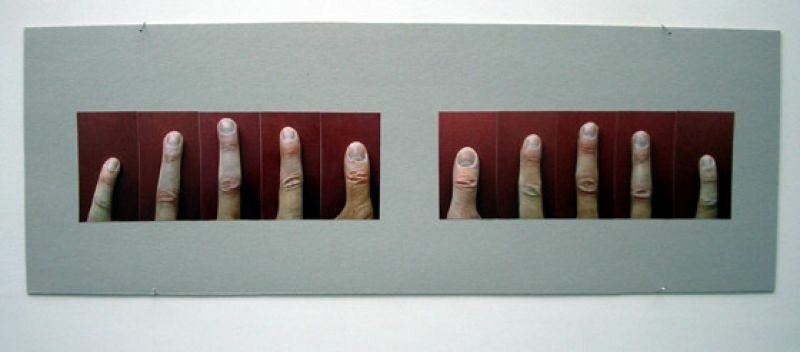

I found another group that fit the same picture: ‘Bored Leg Cult’. In this group one mainly finds photos of people who took pictures of their legs everywhere in the world, sometimes standing, mostly lying down and, for obvious reasons, always without torso. Interesting was how this group completely changed the context of that same picture. In the midst of all the hotel pictures it became a sad picture, but in this group, among all those other legs severed from their bodies, it became happy and funny.

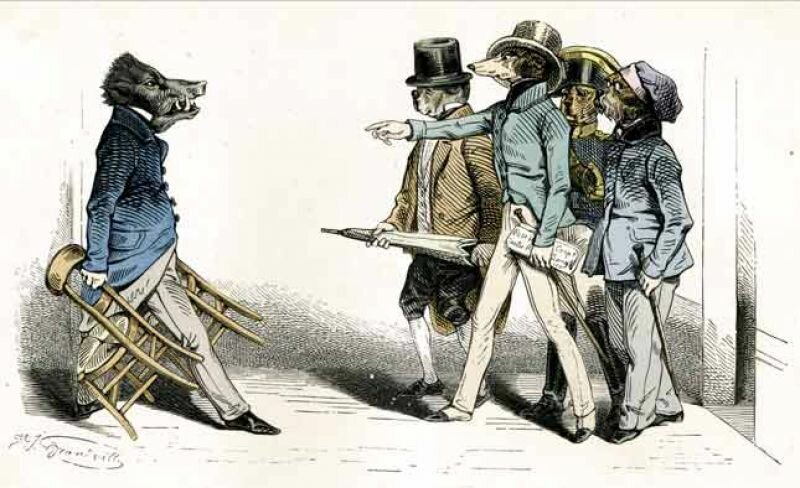

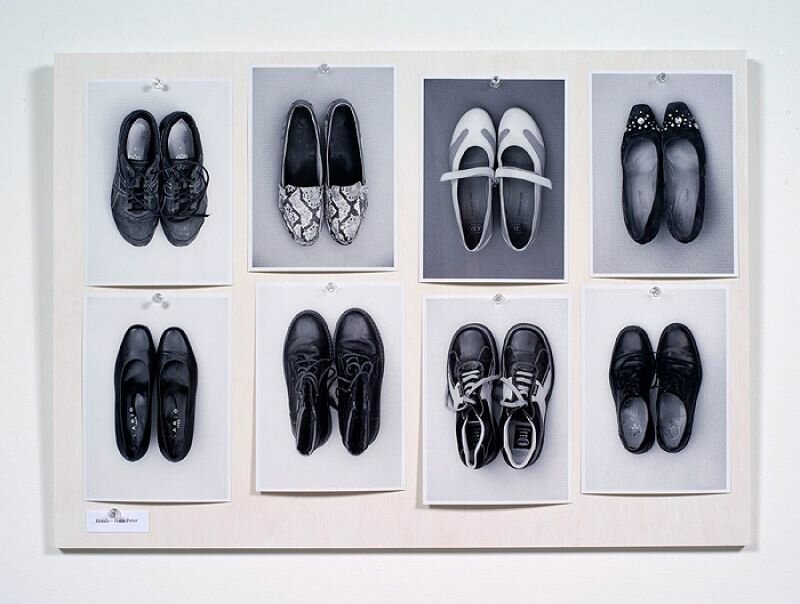

It quickly transpired that I could find groups for almost all my photos. There are groups for pictures of dogs photographed as humans; deserted shopping carts; food items eating themselves; cats with hats; the colour red; people with aids; you name it and there’s a group for it. And the strange thing is that every time I added a photo, the context changed completely. The photo is no longer autonomous, but part of a series. How else to interpret my picture of a shopping cart left behind in a field when seen among more than a thousand pictures of carts in deserts, marshy canals, gorgeous beaches or hanging from trees?

And thus a collection emerges that a sole photographer would have never been able to make, because who manages to find so many shopping carts? A collection that consists only out of pictures that might have been shot without much thought, and yet all of them together create something bigger.