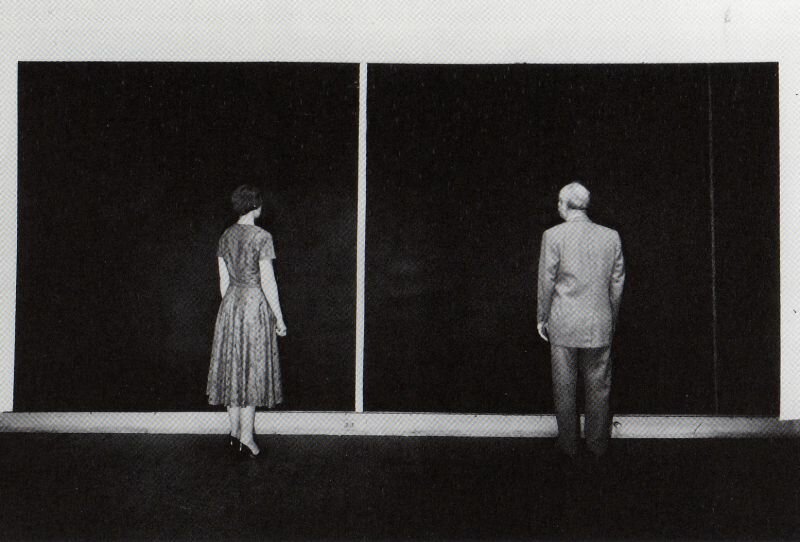

‘There was nothing, nothing at all to see.’ This line, which would become famous, was spoken by a visitor to a Barnett Newman exhibit on January 1950 in New York. Newman presented the monumental monochrome paintings, cut through by a vertical line, for which he would be well renowned later. Paintings without a title, without a motif. In a certain sense, Newman did not want to ‘show’, at least not to show any subject, no image referring to the history of fine art. That was the discovery he had made shortly before: he no longer needed a subject. He advised the viewer to look at his paintings from up close, and not from afar, which one tends to do because of their large sizes. ‘Paintings need to be felt, not to be read,’ was his adagio.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Margaret_and_the_Dragon_%28Titian%29

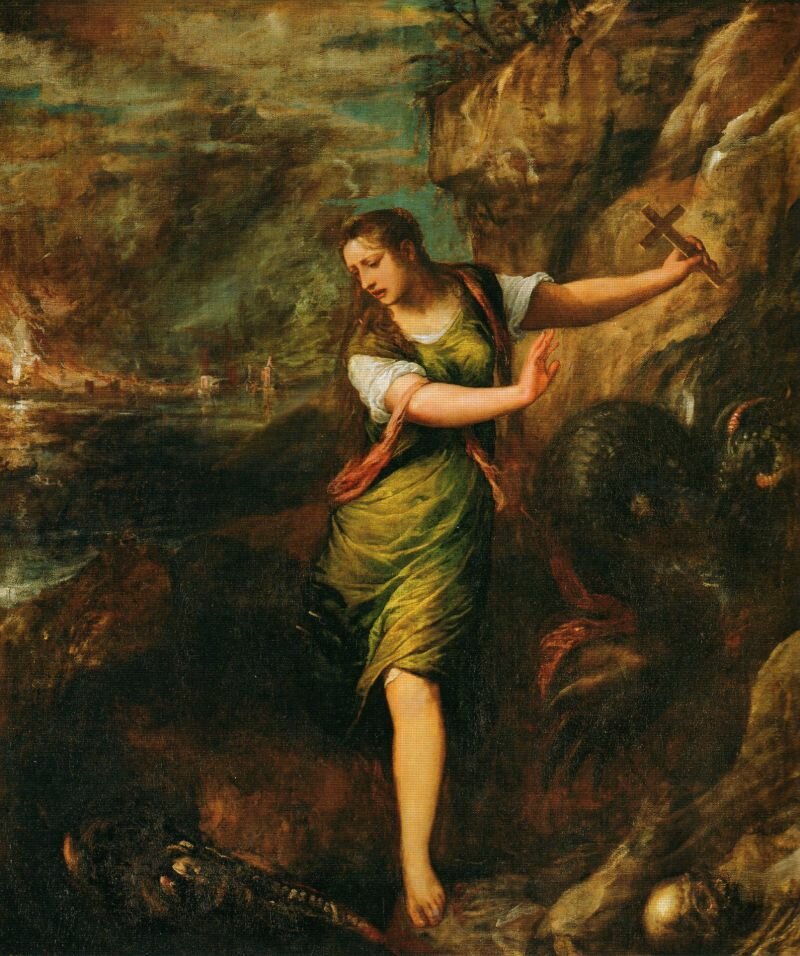

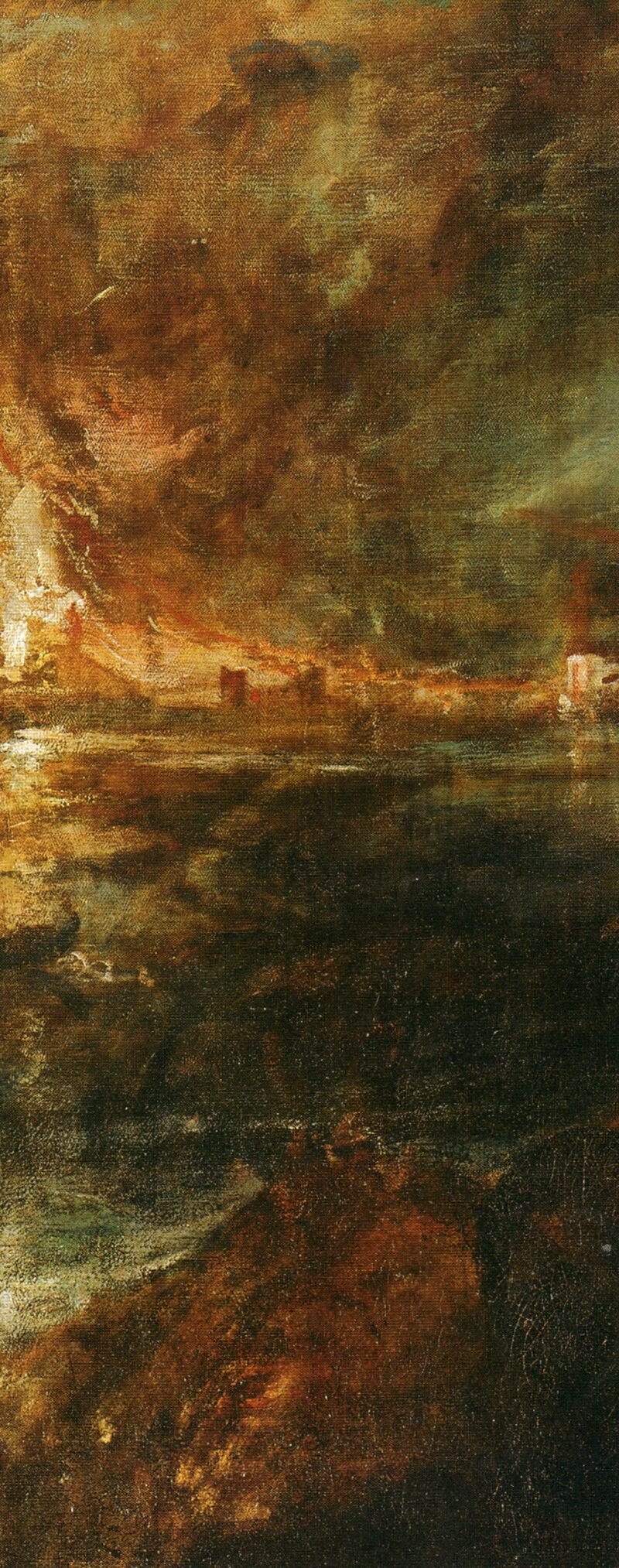

Four centuries before, around 1550, a similar discussion took place. The incentive was the paintings of Titian. At an older age, the master from Venice started to paint ‘invisible’ scenes. No longer did he bind colour to matter and shape, his palette had the figures dissolve in a kind of fog or haze. He built his composition with broad, bold brushstrokes and colour fields. Moreover, he left parts of the canvas unpainted, so that, as his contemporary Vasari put it, ‘one does not see much from up close, whereas from afar the paintings appear to be perfect.’ With ‘perfect’, Vasari meant that Titian’s paintings gave the impression of being alive.

The revolution that is born with Titian and comes to an end with Newman, is that of a category of painting that thrives on invisibility and shapelessness. It is an art of painting that shows the process of the métier, the dynamics of the brush, the use of colour, the texture. But most of all, it is a way of painting that involves the viewer in the work. For it is his position, his place, close to the painting’s skin or from a distance, that determines what can be seen. This form of painting creates the illusion of the viewer as a (co-)creator, an artist, who has to finish the work.

Ironically, this suggestion is raised most strongly by remaining at a distance from Newman’s work, yet by almost pressing one’s nose against the canvas in the case of Titian.

Detail, Titian, St Margaret and the Dragon, c.1559

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Margaret_and_the_Dragon_%28Titian%29