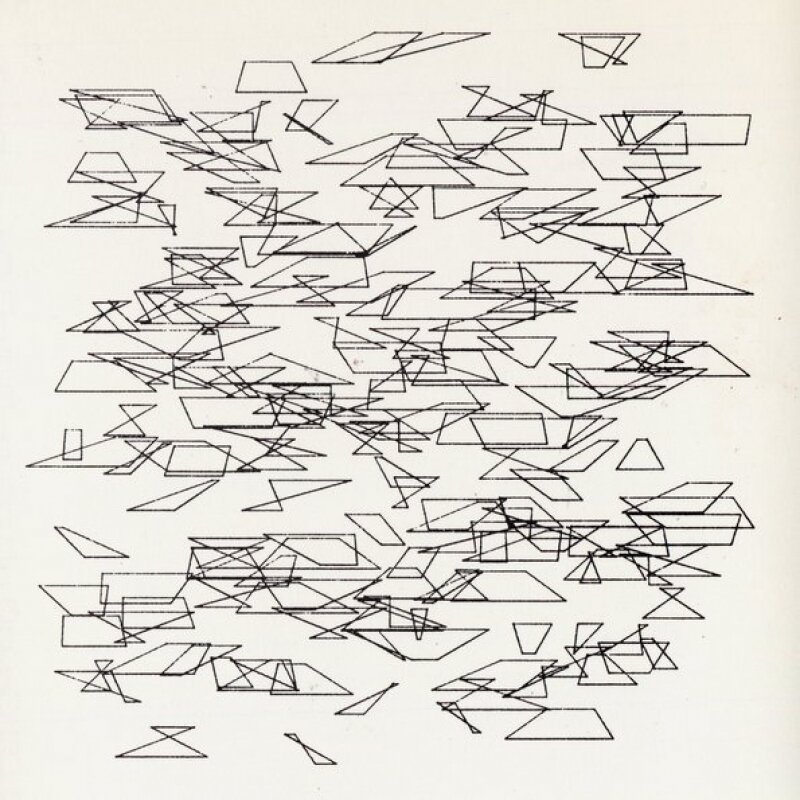

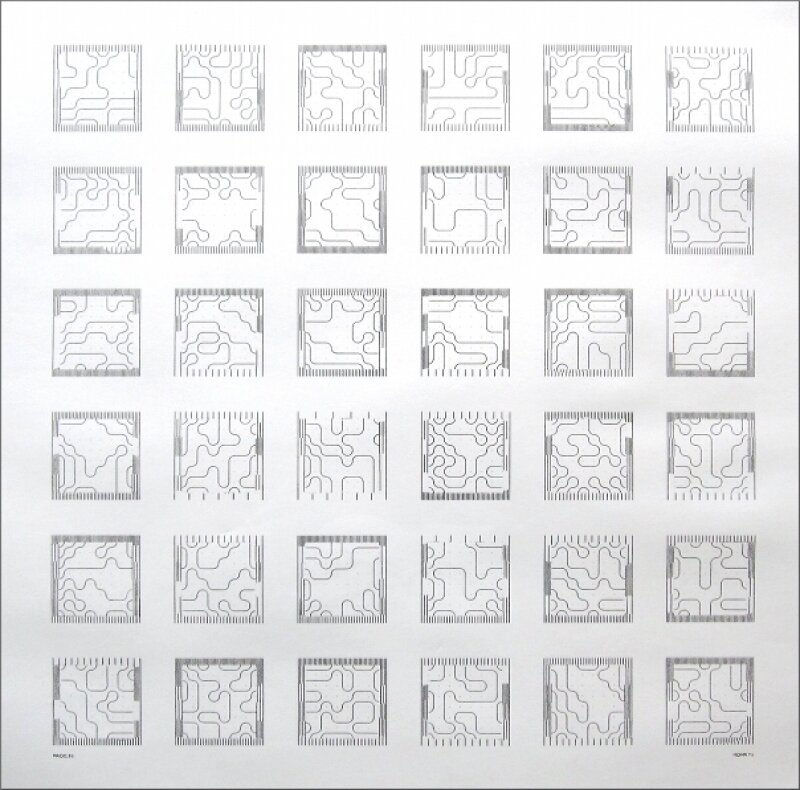

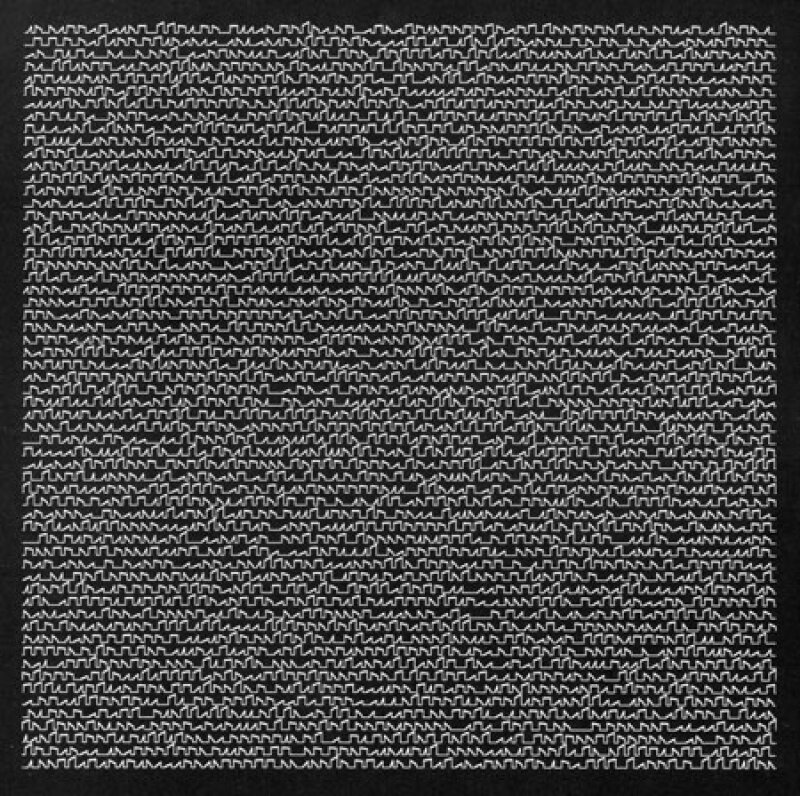

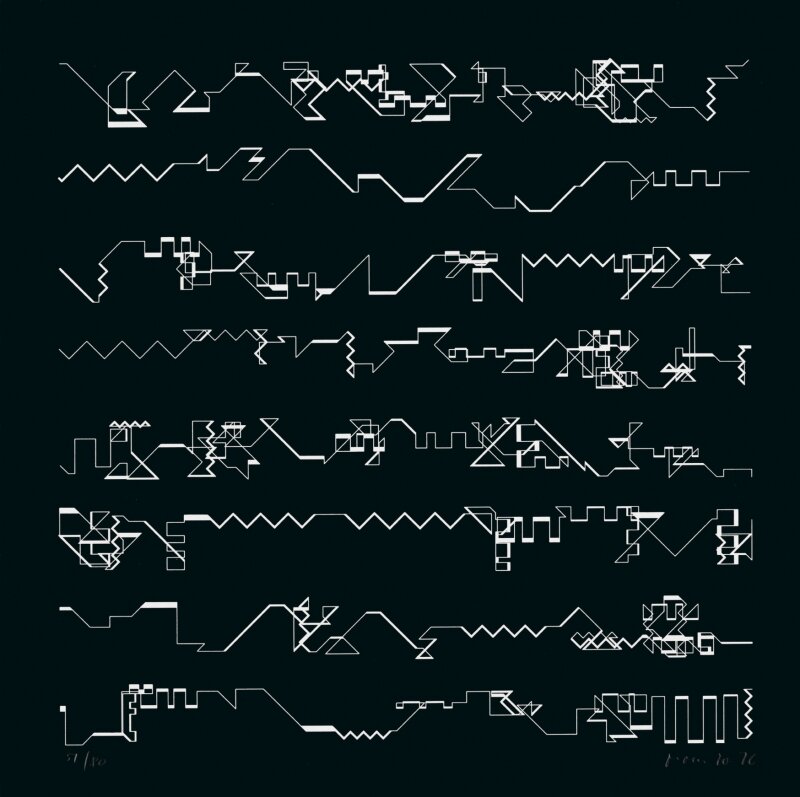

During the fifties and sixties of the last century, the first pioneers in digital art used computers to realize their visual experiments to create algorithmic art. They would write computer programs, otherwise known as algorithms, to generate images, usually by using advanced programming language such as COBOL or Fortran, but also by using machine language. They would often work in the dead of night, whenever a university or research institute would grant them a few hours to make calculations on their expensive IBM-mainframes. These computers were built for computing punch cards, which meant that using them to make visual art became an abstract and mathematical procedure that called for the formulation of rules to determine the construction of an image. The computer carries out the algorithm after which the output is made visible on a plotter (a drawing machine) connected to the computer.

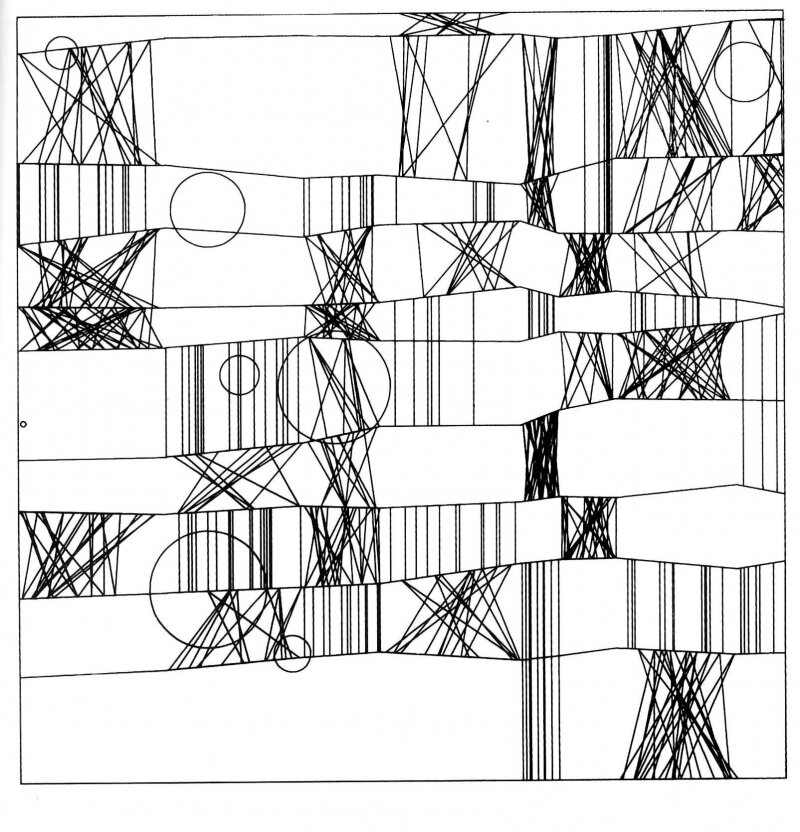

Artists in this field of visual computer art, such as Ben Lapofsky, Lilian Schwartz, Frieder Nake, Manfred Mohr, Edward Zajec and Vera Molna, were strongly influenced by cybernetics and closely linked to the informational aesthetics developing during that time. It became evident that composing algorithms that performed repeatedly to produce the same image was not particularly artistically interesting, however valuable this development would appear for the later advancement of computer graphics. Much more interesting are the algorithms that, when repeated, produce different results. Although the first generation of computer artists created an output of unique plotter drawings, their main artistic interest lies in fundamental research into composition. They also touch upon complex questions concerning the essence of the artistic practice, by often bluntly addressing the question of authorship with computer generated plotter drawings. The question, what is art, is approached conceptually through an algorithm that automatically spits out one unique drawing after another, as though produced on a factory assembly line. Generally, the question was answered by assigning authorship and artistry to the actual formulation of the algorithms. The construction of algorithms for artistic purposes was seen as a scientific form of visual research that opened up a new stage for the development of art.

The works made by these pioneering computer artists is closely linked to the avant-garde movements of the sixties (like GRAV, de Groupe de Recherche d'Art Visuel), and conceptual art. After all, Joseph Kosuth and Sol Lewitt likewise made works that consisted of formulations. Indeed, the end of the sixties saw a short-lived convergence between computer art and conceptual art. The computer artist's attitude towards technology was incomprehensible to those involved in conceptual art and classical art criticism, and was to some even suspect. Nevertheless, many computer artists (like Frieder Nake) were even more radical in their rejection of the bourgeois art system than the conceptual artists, who were operating within the galleries and museums.

The innovations made by the first generation of computer artists are simple when compared to what’s possible now, fifty years later. But their experiments laid the foundation that makes the prefab box of tricks possible. What's more important - for art, that is - is that the computer artists also pioneered in the exploration of conceptual questions that still remain fundamental for computer art.