The Lobster Clasp (1) – A Forgotten Mechanism (2)

Oversized fingers struggle to hold the delicate clasp hidden behind the neck. Hair strands become a forest for the fingers to fiddle through. Your cumbersome thumb repeatedly attempts to hold the tiny lever down long enough to hook the ring but always slips too soon. (3)

The clasp is as important as the pendant it holds. (4)

(5)

Taking the necklace off is always easier than putting it on. Your thumb does not slip. The ring leaves the hold of the clasp easily.

(6)

The larger forms of the lobster clasp sit comfortably in the hands. The internal mechanism plays a sound as your thumb presses down the lever for the opening to widen and then snaps closed when released.

The tactile action of repetitively pressing the lever and releasing it gives a simple sense of satisfaction until your thumb aches from this childish play.

Like clicking the end of a biro, the spring is made tired.

Your thumb is left with a little dent where the tip of the lever has rested.

Sporadically your finger is caught in the gap that the lever moves within.

The exhausted muscle in your knuckle stops you from pressing the lever again. The cheap metallic smell it leaves on your hands is sweet yet unpleasant, toxic and irritating, a reminder of the material’s industrial qualities. (7)

When the lobster clasp finds itself attached to a bag strap, there is tension along the chain the clasp has become a part of. The weight of the bag pulls the clasp to move accordingly. (8)

When the bag is not held the clasp lies lifeless. In the future the clasp will outlive the bag, yet will still be made redundant, as it is no use on its own. They rarely exist alone. (9)

A middle-sized lobster clasp can be found hidden amongst a cluster of keys at the end of a key ring.(10)

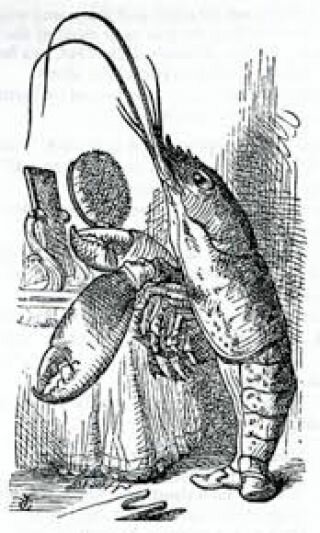

The various sized clasps form a family of differing personalities and purposes all based on the elegant shape of a lobster’s pincher claw. (11)

1

The lobster clasp is an elongated version of the classic ring clasp. The modifications were made in the late 1970s to make the new body sturdier than its predecessor. It is commonly found on western jewellery, keys rings and on bag straps.

2

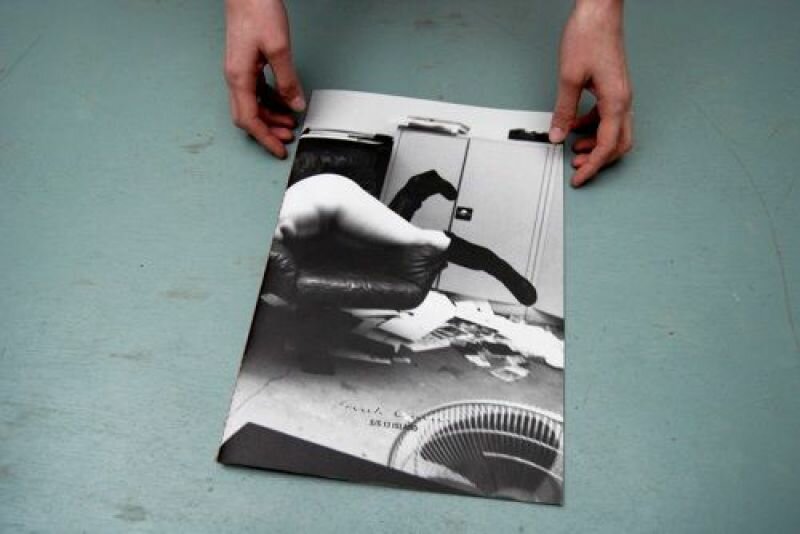

Like the hinge on a door or the brass studding along the edge of a leather armchair the lobster clasp simply functions, often unnoticed or hidden.

3

The clasps are designed to exist firmly closed. Like the form of a book, it rests as a closed object but is redundant if it remains like this. The difficulty in opening the clasp is an inconvenience yet offers assurance and security.

The clasp should be at the front and made a show of.

4

The word clasp has a sense of urgency or importance about it. The clasp on a necklace can hold someone’s most sentimental belonging. The hidden clasp is as precious as what it holds.

5

If the metal hook on dangly earrings were a lobster clasp it would solve the problem of the butterfly falling and disappearing. But perhaps butterflies are better suited to sit behind the ear and a lobster, to secure, hold and protect an adornment of the neck.

The lobster clasp is shaped like an ear but an ear clasp doesn’t seem like something that would snap close or hold anything too tightly.

6

In eastern cultures the lobster clasp is not used as much. In some places an adjustable string and thread mechanism is used and in others knotting mechanisms are used to adjust necklaces over the head and tightened accordingly.

7

This elegant three-part object is the result of several perfected industrial manufacturing processes. The shell is stamped out from a strip of sheet metal and spat out by a customised dye. Leaving behind a train track like pattern along the strip, the shells fall amongst an anonymous pile. Three shells are picked by hand and placed into a mould to be folded with exact precision. They begin to take form and are welded individually. The lever is pressed into shape and the spring coiled.

The shell, lever and spring are pieced together. From a thin strip of sheet metal a three dimensional form is made.

8

The addition of a rotary base permits the clasp to function better.

9

The clasp mechanism is always attached to another form, a door hangs off the hinge like a parasite and fabric smothers the anatomy of an umbrella.

10

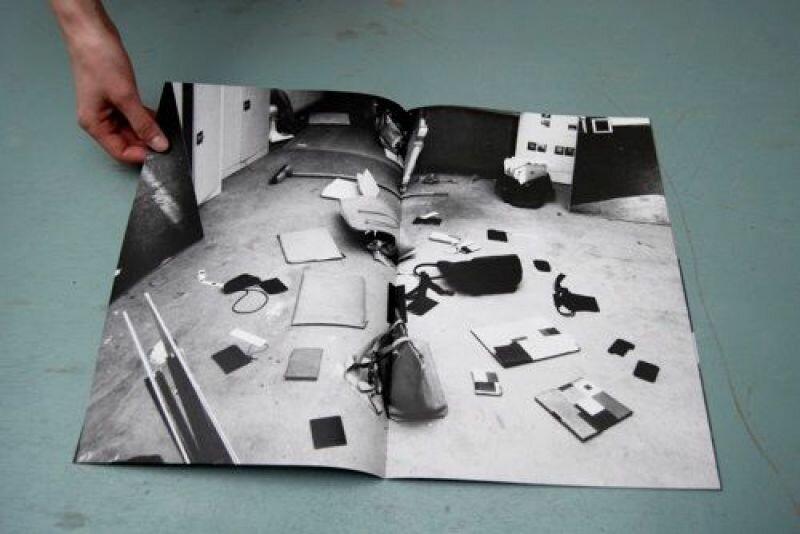

Again, it has company. Sharp crocodile teeth cut keys are fed on to the clasp. The rotary base joins the clasp to an assortment of keys rings and personalised objects, memorabilia, branding, collections, rubbish, the unused and the unnecessary. The surrounding objects play a sound unique to that particular organised accumulation. There appears to be competition amongst the disarray, between sentiments and functionality.

11

A moving lobster cannot be ignored but the resting lobster clasp can go unnoticed.