The art student at the School of Visual Arts in New York baked tens of thousands of cupcakes for a colourful installation in her home state of Dallas,

http://www.pilotafrica.com

Tip 1

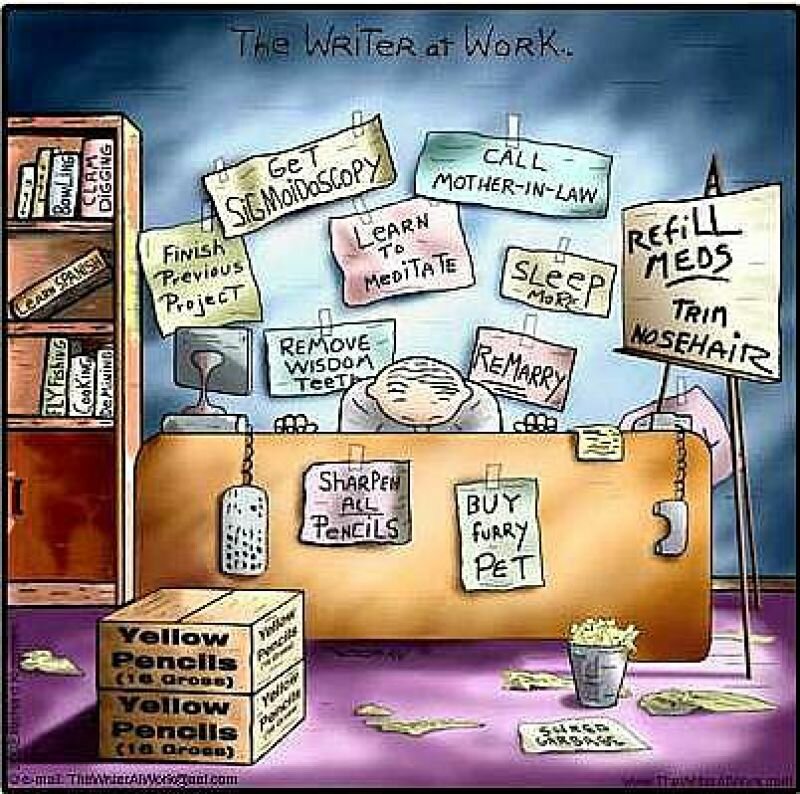

In Stil de tijd (in English: Stand Still Time,) Joke Harmsen writes of how withdrawing yourself from normal every day life can buy you time. This personal or inner time is not to be expressed in units of minutes or hours, but is simply experienced. She’s an advocate for more inner time. Because it’s only when you become aware of the importance of time that you’re capable of reflection and creativity.

Do you think people would be more creative if they have more time?

I think so, because rest, relaxation, and doing nothing are prerequisites to finding a window into that other time. You’ll notice this when you break free from ‘clock time’ and go on a walk, listen to music, or meditate. You’ll find yourself entering another sort of time that seems more connected to the ‘deeper self,’ as philosopher Henri Bergson named it. And inner time is likewise the source of creativity and authenticity.

Do you have any concrete suggestion?

Yes. Keep one afternoon a week free, and don’t be afraid to do nothing.

(Excerpt from interview with Katja de Bruin. To read more see Stil de tijd, Joke Hermsen, de Arbeiderspers

Tip 2

Drawing leads me to a point of total relaxation; you could almost call it an addiction. To work, I need to disable the rational: this is the process. Often, when I begin a work, I try to completely delve into the character that I’m about to make—to write down his or her thoughts and contemplations, but also how that person sees me; and allow the character to speak. There is an enormous freedom in writing, in placing yourself in another’s perspective. A work block is a personal barrier, and means that there’s something you have to admit to. I’ve developed my own ways, my own rituals, to enter that trance of making. Sometimes it might take me a whole day in the studio to enter this trance. I do other things, carry out practical matters, to try and speed up the process. Rituals, daily habits that get the process going.

Tip by Femmy Otten

Taken from the book by Rainer Maria Rilke, Brief aan jonge kunstenaar mandatory literature for the art student

Tip 3

A tip for drawers and painters: buy a cheap sketchbook, a Bic pen, a pencil, whatever you prefer. Fill the sketchbook in one go, don’t stop until it’s completely full, work through the night, drink a bottle of wine and don’t go cutting corners, don’t tear out any ‘failed’ drawings, and don’t judge.

Tip by Erik Mattijssen

Tip 4

Nowadays it seems as though everything has to come from the mind, while it’s movement that gets your body going and brings you closer to your feeling or your intuition. If you can’t get to work, go for a walk, a jog, tai chi, dancing, anything that makes you sweat and move. This will help you on your way. If you’re breaking your head over your work: movement will clear you head and provide room for new thoughts and solutions.

Tip by Wendela van der Hoeven.

Tip 5

My advice to get over a work block is to join in as many projects as you can, even if they feel far removed from your normal area of expertise: participate in performance workshops, work for others, go to Studium Generale all week until you’ve been completely oversaturated with theory and make a drawing every night of how you felt about these things, or what you thought about them. You could also write everyone in your class a letter, organize a miniature exhibition of your work in the store window of an eyeglasses or wool shop, organize a fancy dress party and create a special setting for it, pretend be commissioned to make a fresco for an important chapel, etcetera. You could do these things with others, maybe even some outside of the art world, or you could ask your fellow art students to join.

Tip by Marian Theunissen