24.04.2014

08.10.2013

In 2001, at the invitation of the Bergen School of Architecture in Norway, I visited the coastal island of Utsira. Just getting to the island turned out to be quite an ordeal. This great broken-off piece of rock could only be reached with a small ferry boat, which had a tough time negotiating the spectacular waves here.

The small island, 2 km across, had two harbours. Whilst, due to the wind and the rough water caused by it, the ferry boat was unable to enter the harbour on the one side of the island, it was luckily able to do so on the other. The wind also played a dominant role in the planning and development of the island, or rather, their prevention. There was, for example, hardly a tree to be found; every attempt by a tree to take root here had been thwarted by the cruel wind. Except for one tree, which had made its courageous bid behind the local church. The small building had kept the tree out of the wind, making it possible for it to grow in freedom. When the tree had become so tall that its branches began to rise above the roof of the little church, the wind got its grip on the tree, thus preventing further growth. Because no leaves could grow beyond the edge of the roof, in the course of time, the tree gradually took on the shape of the church, as though nothing could be more normal.

The spectacular result of a tree with a ‘gable roof’ looks at first glance like a somewhat large, artistically trimmed box hedge in a baroque garden, attractive examples of which, created by inventive gardeners, can be found everywhere in the world. With one big difference: this Norwegian house-tree was designed by no one. No one decided how the tree would look. Nor did anyone give the tree its shape out of spite.

The tree’s shape is a result of the specific character of the natural conditions in which it has grown. And in this way, it is a pre-eminent representative of the identity of the island where it stands. Not because a local artist came up with an idea, leading to its promotion by the island’s tourist office, nor because there is a typically Norwegian tradition of creating pointy trees, but purely because of the specific characteristics of the place where it is located.

06.10.2013

Absence

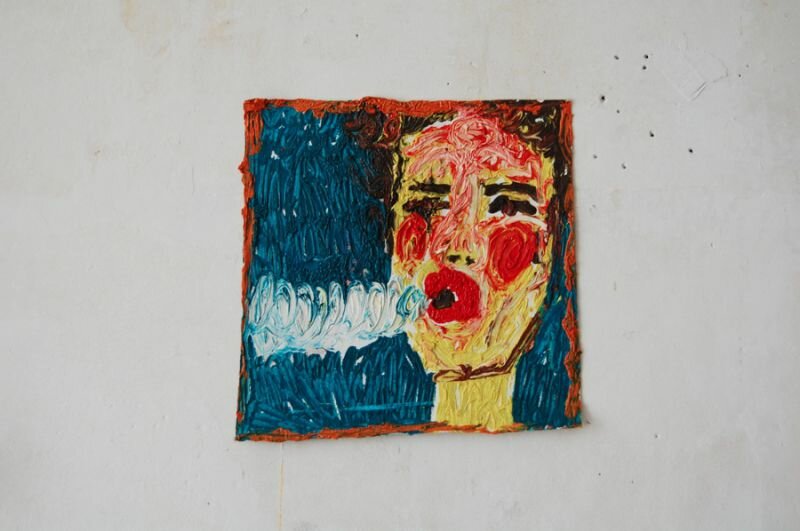

A conversation with Maziyar Pahlevan

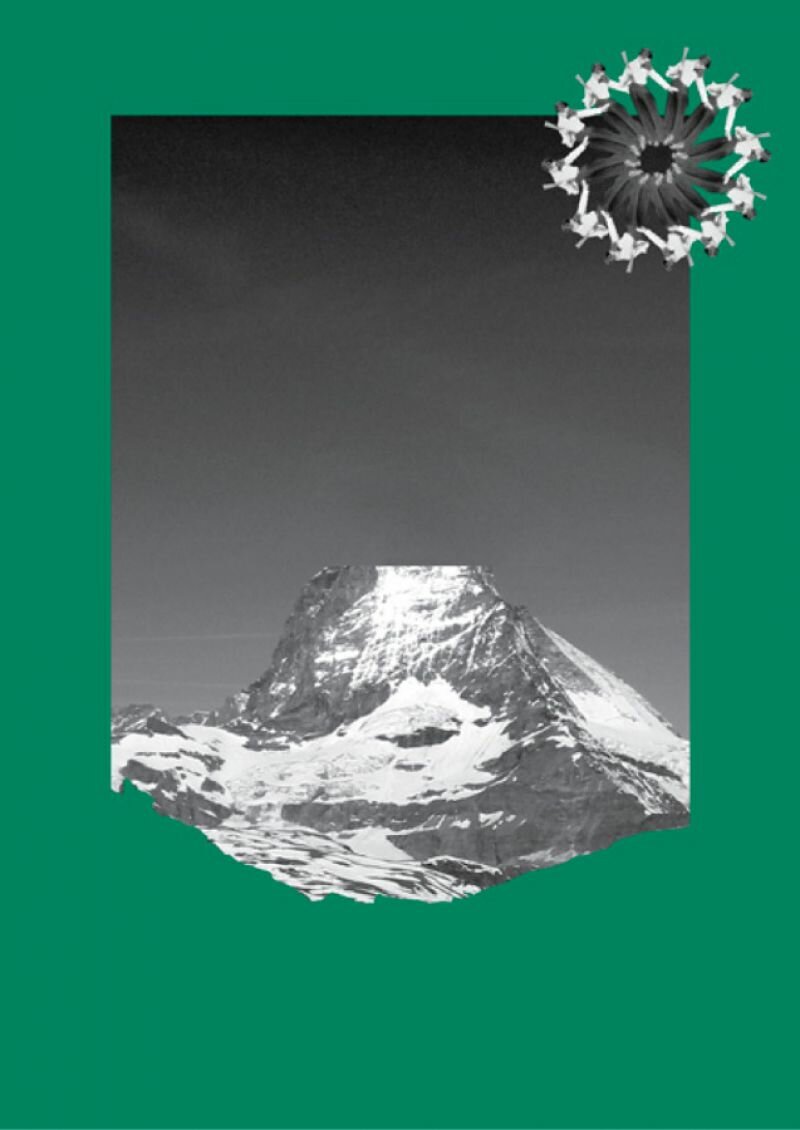

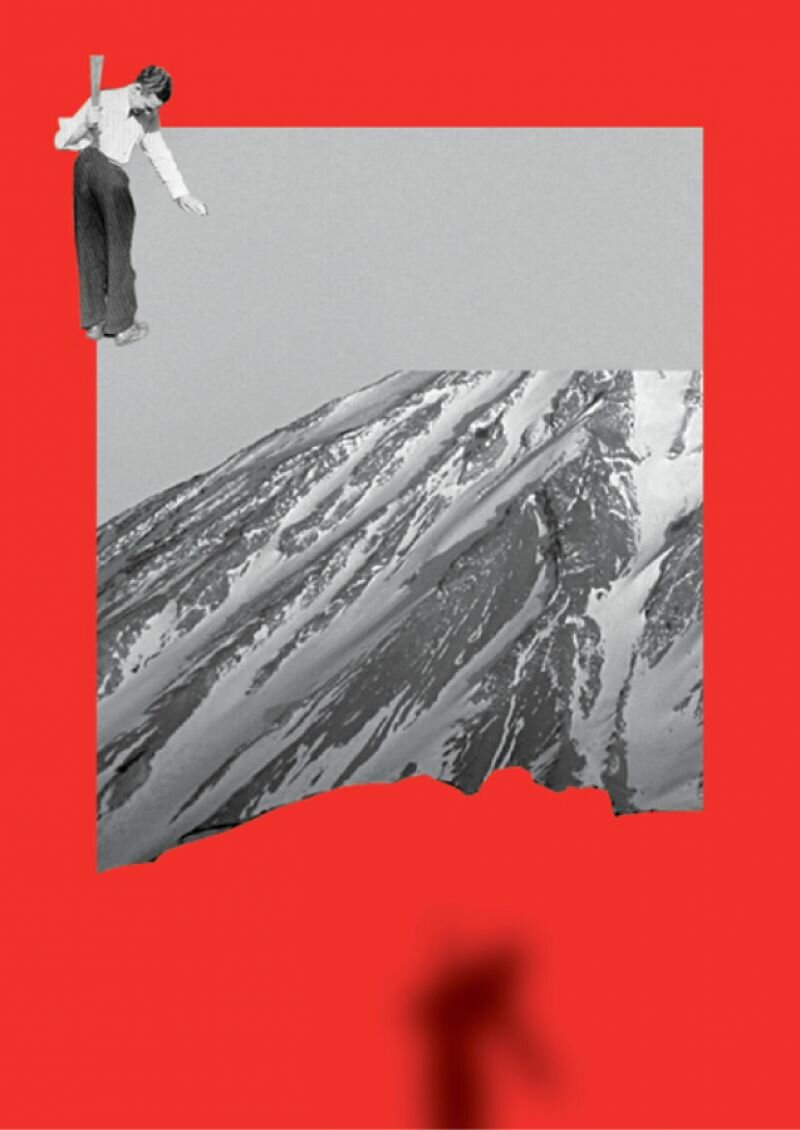

The work by Iranian artist Maziyar Pahlevan (1983) is strongly characterised by the suggestion of absence, missing, and/or lacking, like in the omission of the mountaintops in the series Peakless Mountains, the absence of an opponent in the photo montage series The Wrestler (opponentless,) and even more explicitly in his typographical work, We decided not to be invisible anymore. During our conversation it swiftly becomes apparent that the suggested absence isn’t something merely plucked from the air, and is greatly rooted in the disappearance that preceded the life of the artist; an inglorious and vanished period in the life of his predecessor, a past that has left no trace. Within the mystification of this undocumented period of his father’s life, Maziyar finds the source for his fascination with art.

How did you end up in the arts?

“My father used to study fine art in Italy. This was before I was born, before he’d even mert my mother. Family, friends, and acquaintances often tell me of how talented and driven he was as a young artist. But at a certain point, he stopped his studies and returned to Iran. He found a job and his life took a wholly different turn. In fact, he abruptly broke his ties to art and never mended them. I’ve never seen anything from his active period because he kept. Drawing, and with that, art, was only a temporary thing for him that he only practiced during a specific period of his life, of which no evidence exists.

That’s why I was always so curious about it. I always wondered what it was, the drawing, and art.

I also started very early. In high school I taught my fellow classmates how to draw, and later I studied graphic design at the university of Teheran. However, art education in Iran is much more conservative, and graphic design mostly involved the designing of posters. Since my arrival here, I’ve completely detached myself from my schooling in Iran and who I was there. It’s only here where my work really began.”

What was it about that vanished period in your father’s life that ignited your curiosity?

“You have to understand that family life is vastly different in Iran. Bonds are very close. That’s why it speaks for itself that children become like their parents and live similar lives. In that context, it would have been normal if I had turned into a copy of my father.

I think that my work is partially psychological because I’m trying to understand the exact nature of my relationship with my father. When it comes to my father, I can’t help but ask myself: where did the art go? How could it just have vanished? I felt like I had to search for something that he had lost.

That’s probably also the reason why I love documentation. I document everything that I do, so that it won’t fall into oblivion, and so that I won’t fall into oblivion.”

Do you find it important that he understands what you’re doing now?

“I try to keep my family informed on what I do. This is something I do out of respect, so that they understand how I spend my time. They probably won’t understand the content of my work. They don’t have to.”

Which mountains are depicted in the series Peakless Mountains?

In essence, it’s a very simple image of a mountain without tops, and a man holding a stick, ready to punish. I’ve used the same man in another image and stuck him multiple times in a circular pattern, as though he’s punishing himself. A teacher punishing his student or a father punishing his son… This is very common in Iranian culture and I’ve seen it often. Generations before me have experienced this and next generations will witness it. It’s a pattern of repetition.

The man holding a stick in the Peakless Mountains series must be seen in relationship to the unchanging mountains that I placed in the same image. It’s so deeply rooted within our culture that it’s impossible to ignore, let alone change. You can make a poster of it and hang it on the wall. That’s all you can do about it.”

One of the typographical works in your graduation show was titled We decided not to be invisible anymore. Which “we” are you referring to?

“The ‘we’ first and foremost refers to myself. I use the plural form of the first person to speak of myself and through myself. This, too, is a cultural thing. The first person plural allows me to talk about myself, to show myself, without explicitly using the I-form. It’s a position that allows me to be invisible and visible at the same time. This desire resurfaces in the piece of clothing I designed: cloth for first person plural. When I wear the white robe, I’m unrecognisable. But still, it grants me the ability to still be presenting the work, like in the King of Voracity video in which I wear the piece. I’d like to continue my research into the area of implicit visibility in my future work.

06.10.2013

We did it! Finally we’re let into the garden bordering the study. It’s just us two, accompanied by a burly guide who solemnly walks ahead of us in silence. It was well worth the effort: this is one of the most beautiful gardens we’ve ever seen.

The quote “Burl Marx was a painter that uses plants as paint and the soil as a canvas” comes to life before our eyes. As a painter he experimented with light, colour, the texture of stones, plants, trees and shrubbery, seeming to have a preference for plants of exceptional colour and leafage. Many of the rare indigenous species that he introduced in his designs were tracked down in the jungle by Marx himself and planted on the property. Here in the open air, he assembled a rich collection of Brazilian plants and trees, all the while researching how to apply them in his composition.

Besides being a collector, Burl Marx was also fantast with a great sense for drama. Boulders were stripped of their usual vegetation and were instead covered by cacti. Dozens of Asian orchids were imported. Rare trees, whimsical waterfalls, even a monumental marble façade (shipped over as a gift from the city of Rio) are characters in this exuberantly performed theatre piece.The show is a spectacle in which the artificial and the natural seem to compete with one another, only to settle for a harmonious balance that animates these gardens. No nude naturals to be found here. Instead, Marx flashes contrasting, nearly toxic colour combinations. At times it’s hard to believe you’re really there and not an extra in one of the better Walt Disney cartoons filled with fantastical birds, butterflies, and lizards. He most definitely wasn’t modest or afraid to take on nature and, with utmost precision, to choreograph her like a true dramaturge. But above all, he presents us with an ode to nature, by putting all he could imagine into play.

05.10.2013

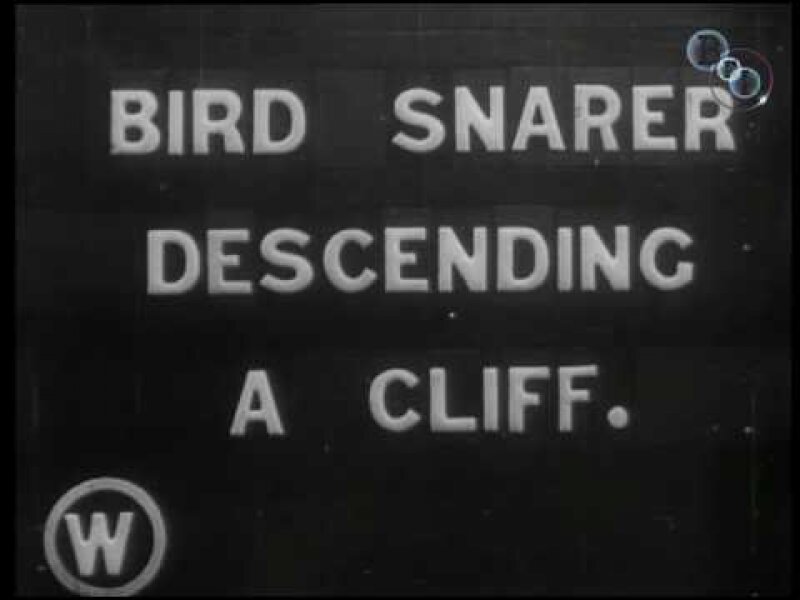

In 2003, Mels van Zutphen made a film about St. Kilda that he unfortunately is no longer permitted to show due to the archive material’s rights.

St. Kilda, just off the west coast of Scotland, is Britain’s most remote cluster of islands, and moreover has the highest cliffs. The archipelago is still known for its large population of puffins and northern gannets. For centuries, a small community inhabited this small area of a few square kilometres, almost completely isolated from the outside world. The last inhabitant was evacuated in 1930. The only two survivors from this era are now elderly and difficult to contact. 'St Kilda' is a film about rituals, birds, bachelor exploits and being easily offended.

Some archive material can be found online:

Some other material can be found from the EYE archive