Compared to nightsticks, Kalasjnikovs and bats, whips don’t come across as very intimidating. Who ever heard of a war won by an army armed with whips? Or of bank robbers using whips as their method of coercion?

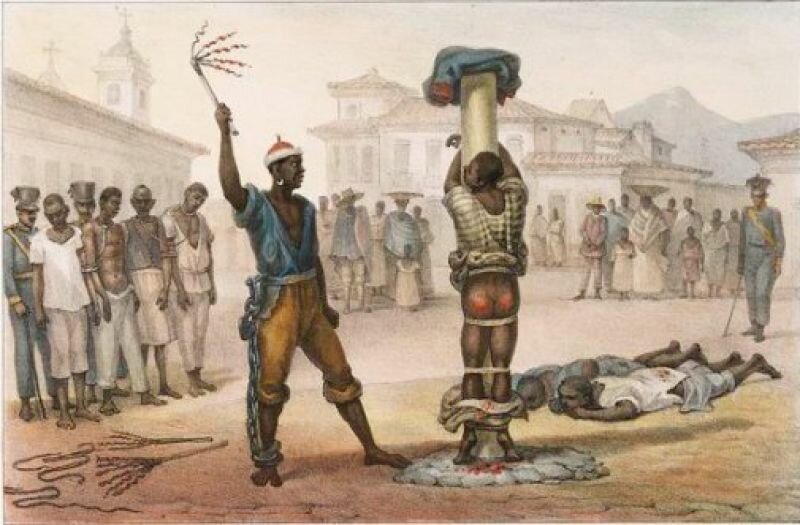

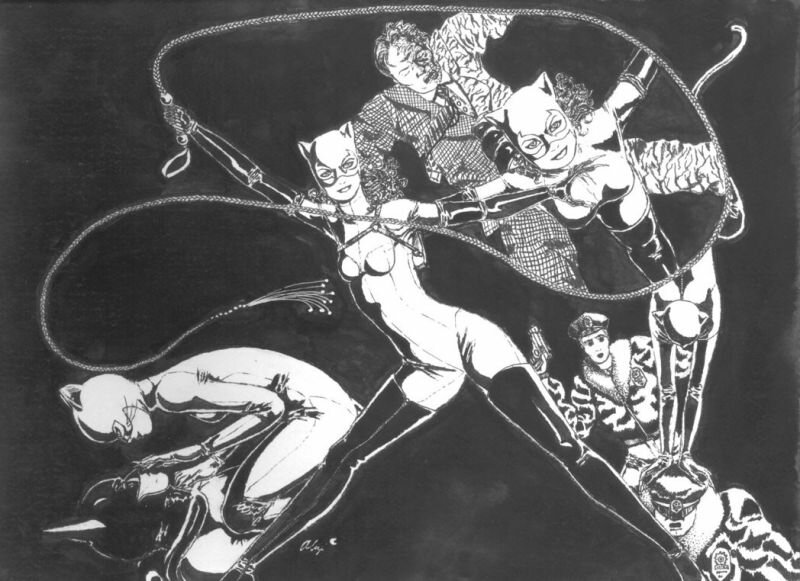

The whip’s power to induce fear is as good as lost in the Western world. Slaves were whipped to death. Children were covered in welts after educational beatings. Now, the whip has become a decorative attribute, a prop. From being an instrument of power, it’s transitioned into a representation of an instrument of power, a symbol.

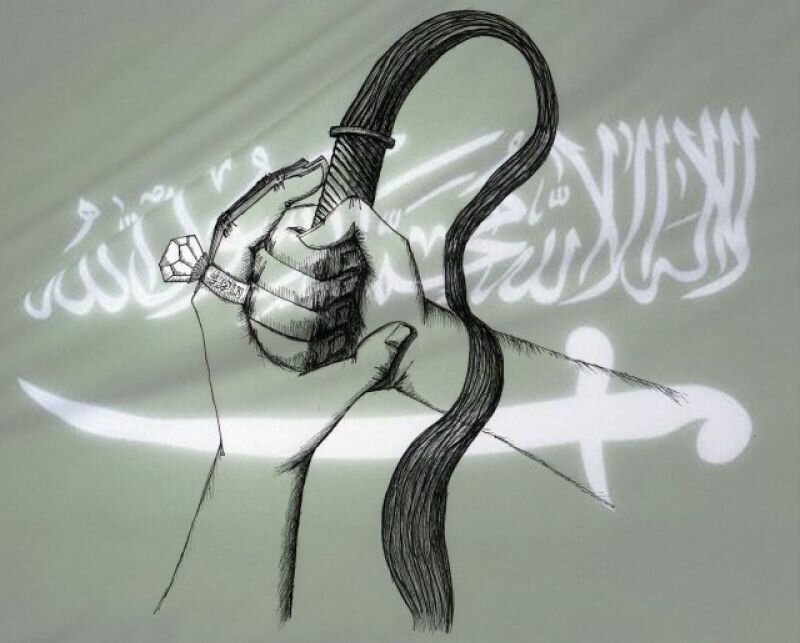

In other parts of the world, the whip is still used as an instrument of punishment. For example, two Saudi Arabian men were recently convicted to two thousand whiplashes and ten years of imprisonment. They had uploaded a video on which they were dancing on a car naked.

The other day, a smart looking older gentleman lifted his cane towards me and yelled: “Would you like a free slap?” I politely declined his offer. Later I regretted it. Why hadn’t I enquired further? Maybe the gentleman could have provided me with some convincing arguments regarding the free slap. What I know for sure is that I would have interpreted his offer much differently had he offered me a knife wound, or a gunshot wound. I would have been scared, now I was merely surprised.

Why does the whip no longer strike fear into the hearts of Westerners? Has the whip been overtaken by large scaled, advanced weaponry, that in comparison transform the whip into an old fashioned, primitive, and nearly innocent object? Are we so inexperienced with the force of the whip that even our imagination falters?

Erotica thrives on taboo. It comes as no surprise, then, that the whip is a staple item in every sex shop. Like the penis, the whip seems to possess a certain level of autonomy, although both remain dependent on a body in order to come to life and to discharge.

One particularly commanding whip is the metal chain whip, made of two metal rods joined together by metal rods. Because of the many chain links between the rods, it takes endless practice in order to comprehend how movement courses its way through, and furthermore how to use it without injuring yourself.

The chain whip is popular with the Taoist and Buddhist monks of China. Into the air they endlessly crack their formidable whips, breaking through the sound barrier in their search for salvation.

Dutch theatre maker Boukje Schweigman and dancer Ibelisse Guardia Ferragutti trained with these fighting monks, and in 2011 made the performance Zweep (Whip.) In a making of the film, Guardia Ferragutti says: “A whip has no master. The master is the whip itself.”

Raymond Talis, author of Michelangelo’s Finger (2010,) explores why humans, in contrast to animals, point using their fingers. According to Talis, we point thanks to our consciousness. We experience ourselves as separate individuals, and thus do not become one with our surroundings. But in our fellow humans, we recognise isolated peers, we can see each other looking. We’re able to guide the gaze of the other by drawing invisible lines using our eyes or our index finger. Is the whip an extension of the index finger, with which we can impose our will onto the bodies of others? Still, no one will ever have complete control over a whip. The first flick of the whip may be under your control, but you’ll never know exactly what path you’ve set into motion. Before you know it, the whip you’ve cracked will rebound and hit you with twice as much power and take you down. The real force of the whip remains impossible to truly fathom.