Castle, nightclub, palazzo.

Esquire, duke, baron.

Industrialists and rock chic.

Jazz pianists, acrobats, Coco Chanel.

Eight hundred quart bottles of the finest champagne, sparkling in the morning sun.

The soft caress of mink and sable furs.

Tuxedo and black tie.

Celebrities flanked by a leashed cheetah or lion cub.

The squirrel monkey painted blue on the shoulder of the host, the dazed boa constrictor nestled in the bosom of the marquis.

Yves Saint Laurent, Pierre Cardin and Christian Dior.

Salvador Dali’s walking stick of old Catalan walnut, tapping the beat of a waltz; red ants crawling between the space in the double glazing of his spectacles, Amanda Lear at his side.

Walking, arm in arm, with Kees van Dongen, Tristan Tzara and Marcel Duchamp: the Count and Countess of Noialles.

‘A lost world,’ as Nicholas Foulkes describes the costumed balls once popular in the world of the old nobility, haute bourgeoisie and artists.

‘Holding a ball is not the same as having a ball’’, Baron De Rothschild declared in the memoirs he wrote towards the end of his life as a banker. The wealthy lover of extravaganza carefully summed up each step necessary in the preparations for a successful costumed ball; from the table arrangements to the flower pieces, the proper lighting and decorations to the choice of invitees and the menu. As Rothschild describes, it appears that the organisation of a high concept party is equally complex and complicated to that of a museum exhibition, military operation, or theatre piece.

The host or hostess must never lose sight of the ultimate goal: the escape from grim reality through jubilant escapism. ‘Is it not our duty to,’ wrote Rothschild, “each to their own style and taste, enrich life with all that is superfluous and lush, and to embellish it with those few short flashing moments of elusive beauty?’

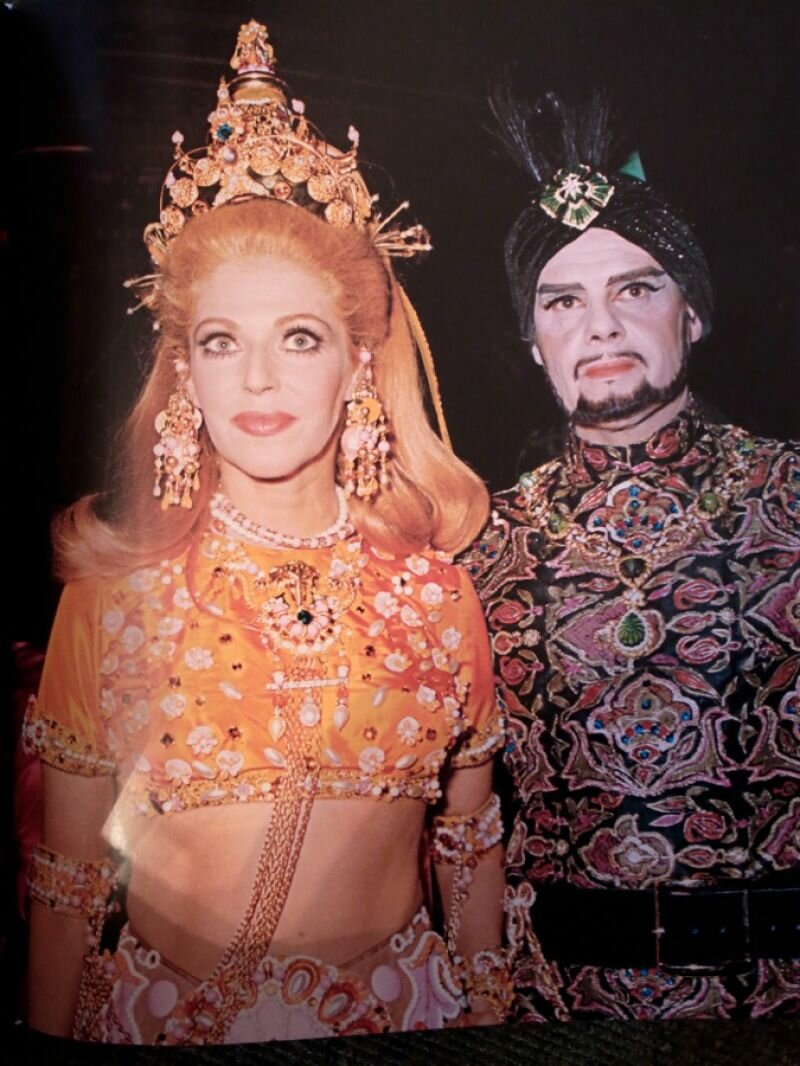

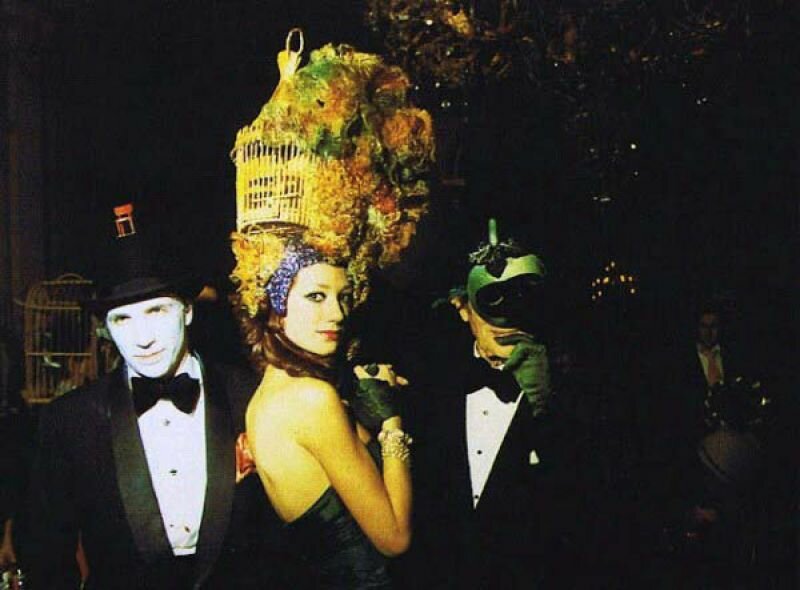

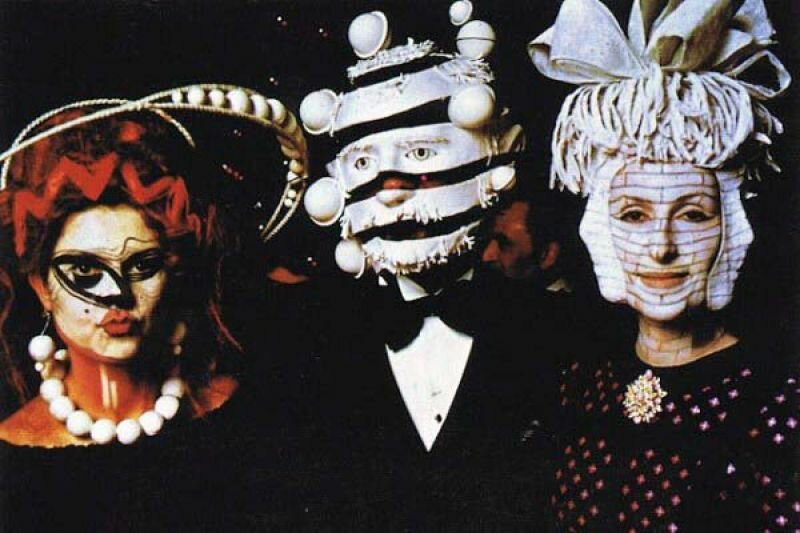

The ball as a carefully orchestrated moment of ecstasy, a whirlwind of luxury, beauté, volupté, a hyper stylized flight into another time, a finely construed Gesammtkunstwerk, as ephemeral as the thin fragrance of a jasmine perfume from the Shanghai delta... to escape one’s self is to live twice as intensely.

Style is everything, wrote gutter poet Charles Bukowski (‘Style is the difference, a way of doing, a way of being done./Six herons standing quietly in a pool of water,/ or you, naked, walking out of the bathroom without seeing me.’)

Style is what makes the ball’s invitees different from the ordinary man.

Style is what restrains the partygoers in their costly costumes from degenerating into a dishevelled drunken stupor.

You won’t find them in a back alley with their black tie hanging at their navels and besmirched with stains from the evening's lobster meal, torn spaghetti straps fluttering in the cool morning breeze, shouting from rooftops or stumbling through hysterical androgynous declarations of love for Amanda Lear.

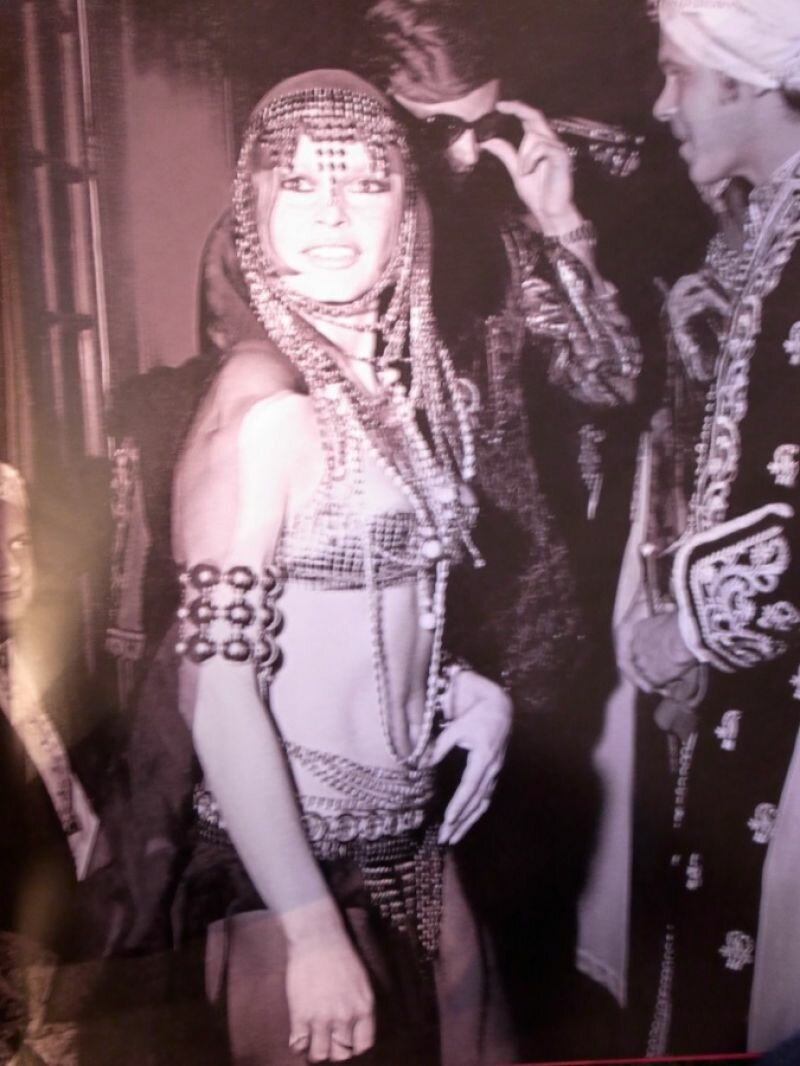

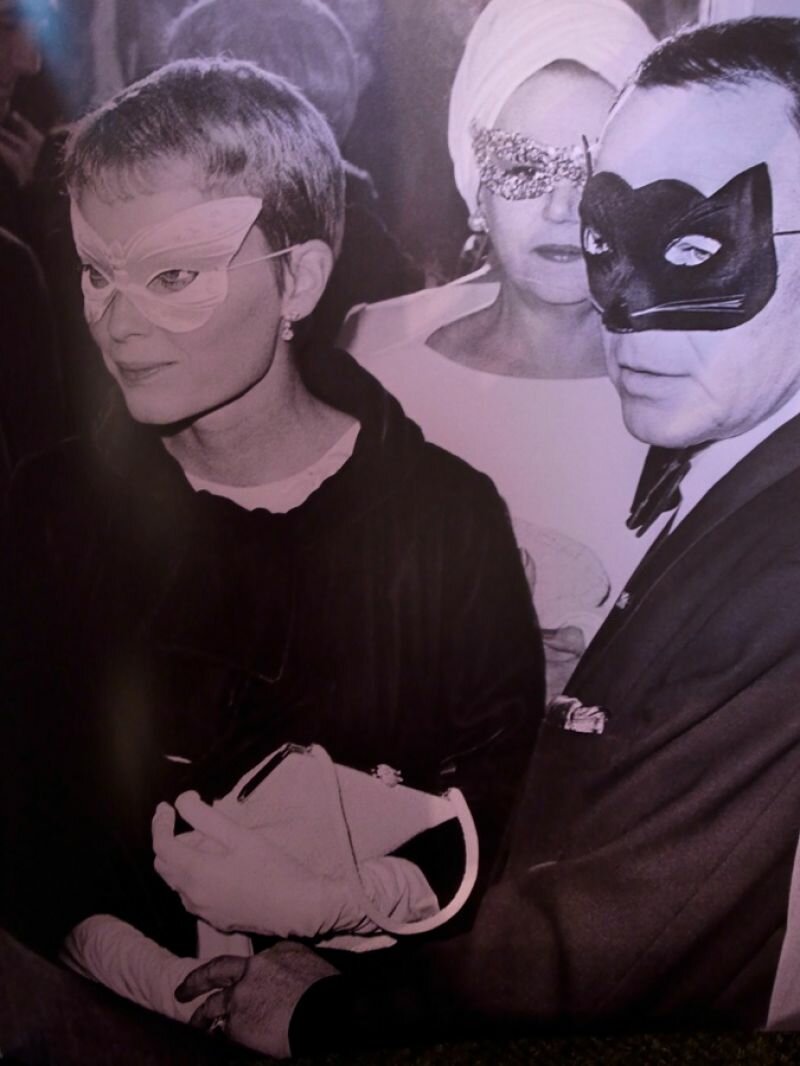

In his erudite study of the sociology of the ball, Nicholas Foulkes comes to the conclusion that he who dons the costume of a seventeenth century sun king, disguises himself as Baron Charlus from Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, or she who makes herself up to be a mysterious princess from beyond the Bosphorus finds their delirium within the perfection of their stylization.

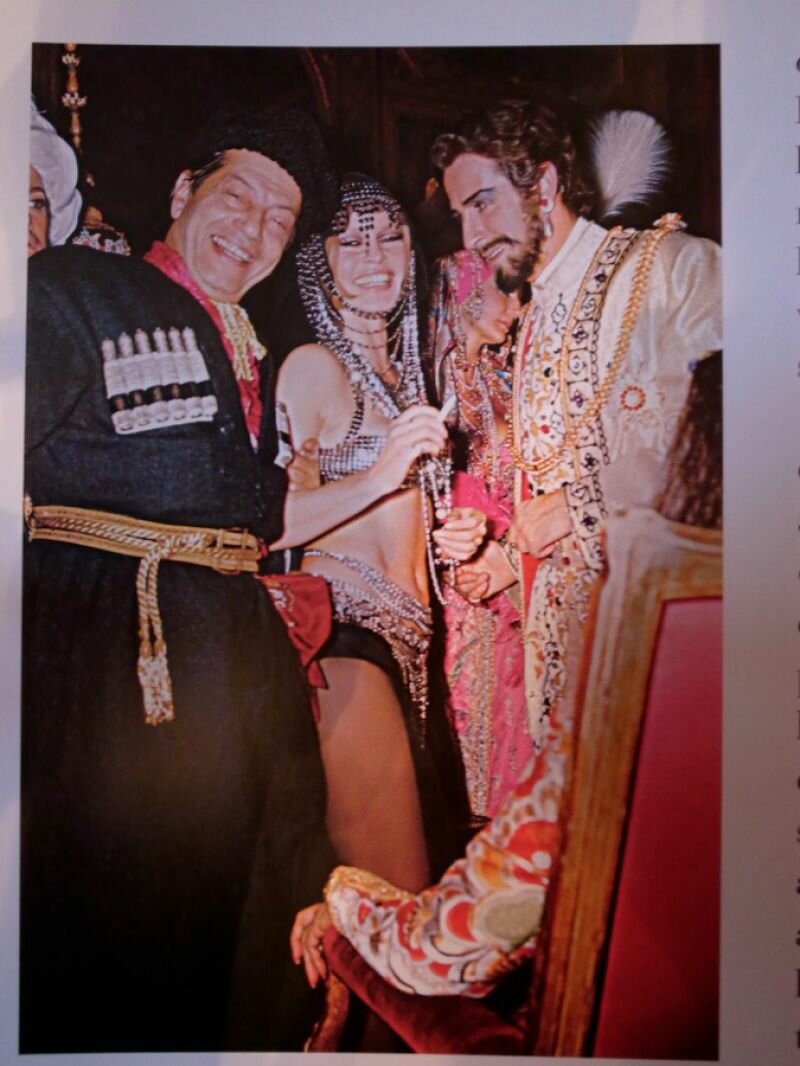

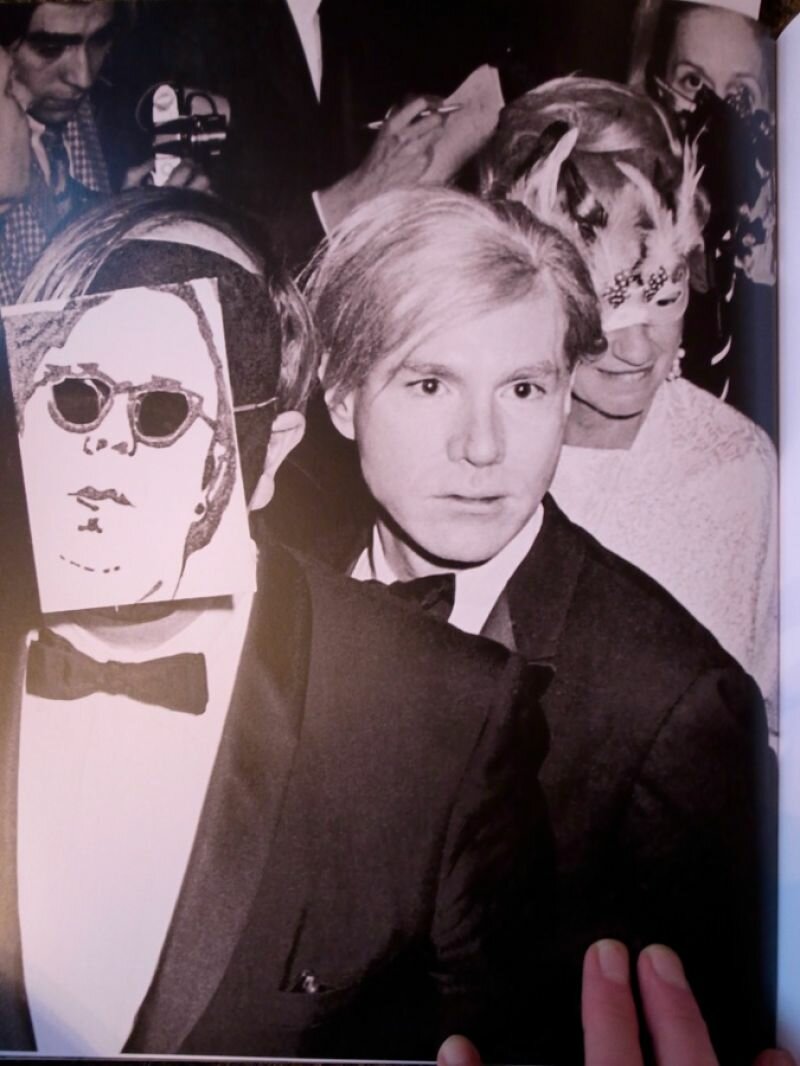

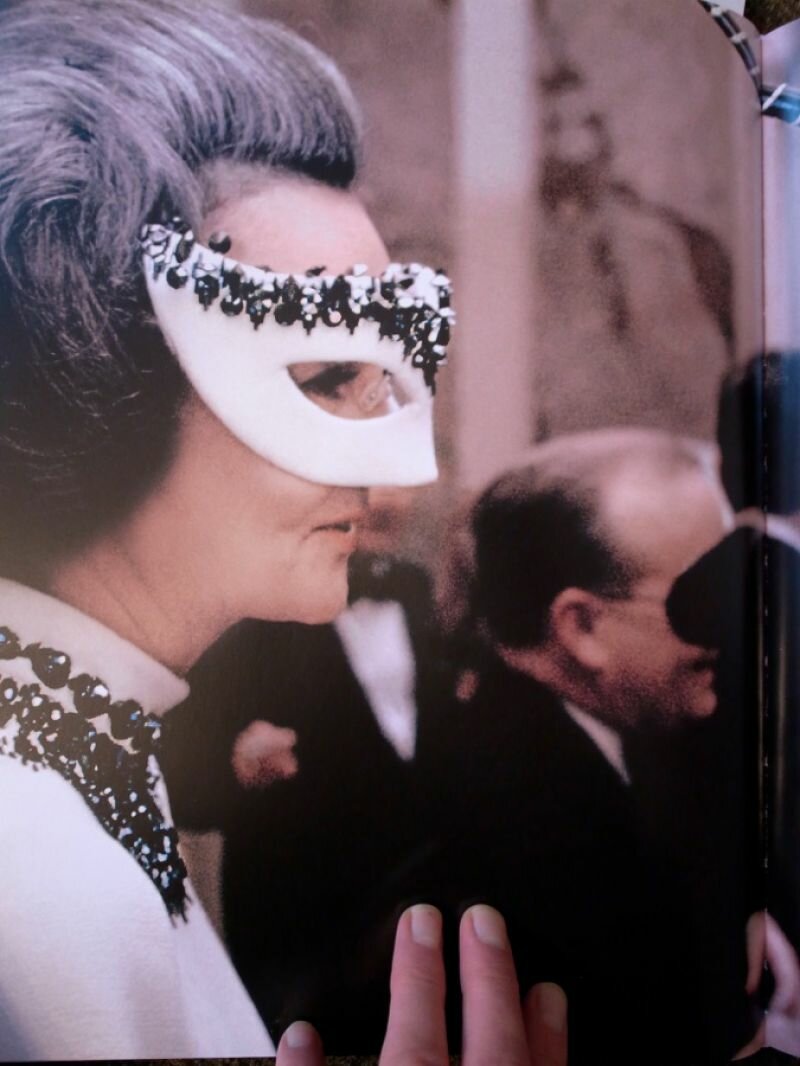

He selected photographs from parties including the Romanov Ball in 1903 in Saint Petersburg, where almost every guest was a member of the Russian nobility, and the Proust Ball, organised by Rothschild in 1971 where a curious mix of low nobility, pop stars, children of the Extremely Rich (‘spoiled brats’) and famous writers and movie stars dotted the ballroom.

The Proust Ball is where royal photographer and aesthete Cecil Beaton viciously mentioned Elizabeth Taylor’s shockingly vulgar appearance, ‘a geriatric Cinderella with plump, rough hands and an oversized diamond hanging around her neck.’

After this, Rothschild said, it seemed as if an end had come to an era.

The temporary nature of the ball is similar to the temporary nature of intoxication. All that remains is, cliché of clichés, the memories. The after images that nestle themselves within the hard disk of the mind are those of the hypnotic mise-en-scène, the decor that immerses the guest into another time period, not to mention the artful delights produced by the Chef, the blindingly beautiful costumes and the quicksilver je-ne-sais quois sensation so characteristic of all festive occasions where champagne flows freely.

It’s precisely this fleeting, short-lived moment that photographers like Man Ray, Cecil Beaton, Baron de Meyer and Horst P. Horst managed to capture, in a way so very different from the average party.

Take a look at the footage reminiscent of Eyes Wide Shut, shot by Jacqueline de Ribes, cousin of Count Étienne de Beaumont, the mastermind behind many widely spoken about balls from 1915 to 1955. At Don Carlos de Bestegui she appeared thrice, flanked by two women of the same height and posture, hidden behind identical masks, dressed in the same gowns, adorned with the same jewels and headdress. An impressive feat at styling, a perfect disappearing act of the ego, a true work of art ‘that comes to life for merely a few hours, that illuminates the night in all its multicoloured splendour and is doused by the first light of the slowly creeping grey-pink dawn’. And that’s exactly how it must have been. What a shame we weren’t there.

*Nicholas Foulkes, Legendary Costume Balls of the Twentieth Century. Assouline Publishing, New York, 2011.

Foulkes wrote the luxuriously published Legendary Costume Balls of the Twentieth Century, in which nine legendary balls are examined in word and image.