Tamara Robeer (NL 1981) sees herself as a storyteller, researcher and explorer of life using photography, writing, and conversation. For Tamara, it is important to share stories on how we relate to ourselves and to the other.

1000 Things is a subjective encyclopedia of inspirational ideas, things, people, and events.

Read the most recent articles, or mail the to contribute.

Tamara Robeer (NL 1981) sees herself as a storyteller, researcher and explorer of life using photography, writing, and conversation. For Tamara, it is important to share stories on how we relate to ourselves and to the other.

You can wake me up at any time of day to talk about sexuality, intimacy, and relationships. It’s like an addiction to sugar: take one bite and an urge for more continues to resonate within mind and body. As long as I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by our humanity, our raw desire for intimacy and the many different ways in which this takes form.

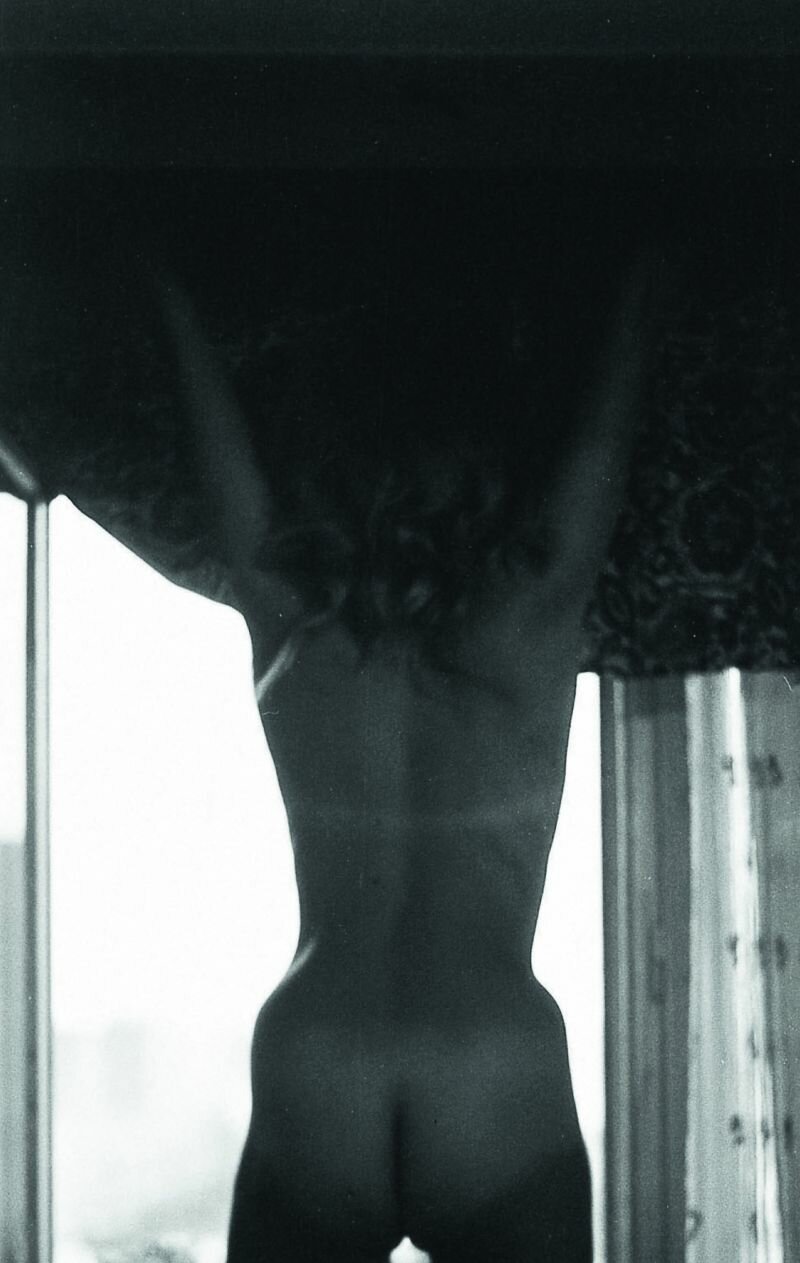

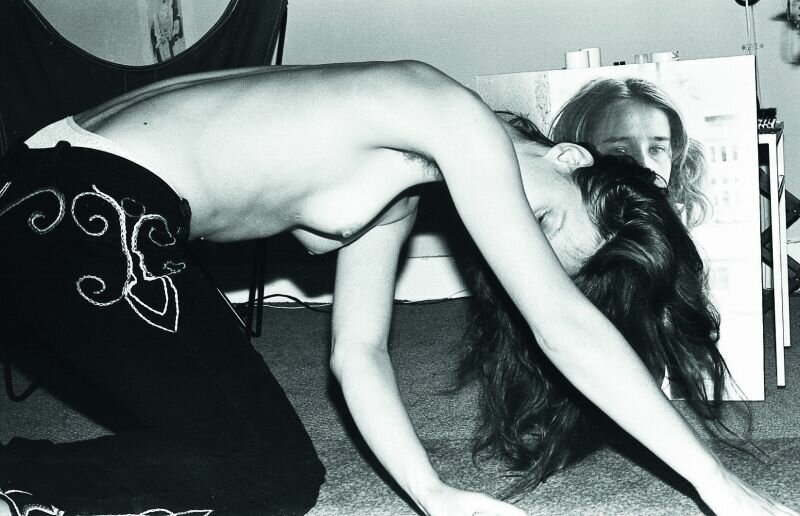

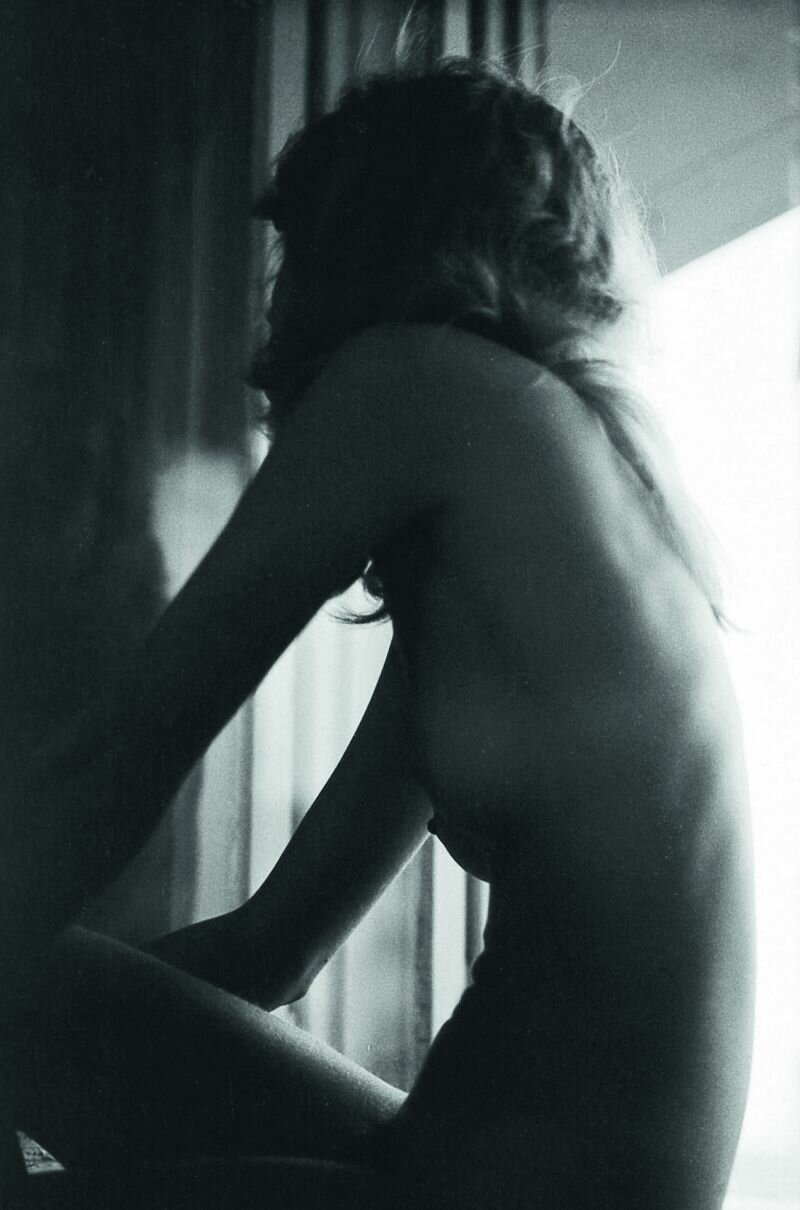

After my father passed away, I found an entire archive of black and white negatives. Among the thousands of images of his travels through Eastern Europe were a few films of naked girls. As it turned out, my father photographed many unknown (to me) girls in the nude. Not only their bodily forms, but also with their legs spread open, without scruples. I had always thought my father to be incredibly prude, but it turned out nothing could be further from the truth.

I was even more delighted with my find when I stumbled across a few rolls of film depicting my 25 year old mother strutting around bare naked. Instead of feeling repelled by the idea of looking at my naked mother (even though she’s forty years younger,) I felt I was simply looking at a young couple in love. Two teenagers playing the game of sexuality before the lens of the camera.

My father’s photographs can be seen in a controversial light when one considers the context in which they were taken. A number of photos were made in my mother’s parental home in Bucharest, Romania in 1974. The country was still under the strict reign of Ceausescu’s communist regime. The other half of the photos were taken in my father’s bedroom, who at the time was living in a house joined to the grand church in The Hague’s city centre. Sexual intimacy linked with ideologies inherent to a communist regime, and naked photos made by two teenagers within the walls of a church, portray a clash with the pertaining social norms and values of the architectural spaces in which they were taken.

As soon as the combination of roles and context do not fit within our accepted contemporary social conventions, we cross a line whereby story and image are experienced as shocking. Much more so than when we are merely confronted with an explicit image of a sexual act. The friction lies within the story, not within the visuals. What happens if I release and discard all narrative, reduce it to insignificance? In the moment of making theses images, there are no narratives, judgements, or social conventions. In that moment, there is nothing but the sense of being human, of intimacy and connection.

Of course, I showed these photos to my mother. Her reaction was, ‘Oh god, what a bush of hair I had down there, but you know, that was in style back then’.