There came a day when someone decided that an end should come to the many unanswered questions in the world. This person opened an office with visitation hours, just like a city hall or the post office. You’d draw a number, and once it was your turn, you’d walk up to the counter and ask the employee your most pertinent question. With an answer in hand, you’d walk out the door feeling satisfied.

I wish it existed. Only I wouldn’t know which question I’d ask first, because I have so many: where does the light go when I turn off the switch? What came before the big bang? Where is the end of the universe? Is there a God? What is infinity? Do invisible things exist? And if that wasn’t enough, the answers to these questions would most likely prompt even more questions.

I’m in Berlin, standing in front of the doors to the institute for “unanswerable questions and unsolvable problems”. The building is on a corner and covered in white sandstone and tall mirrored windows in metal frames. “Denkerei” is written in pink letters above the front door. At first glance, the building is more reminiscent of a bank office or a fancy, but dated, hotel. To the left and the right of the door, the windows are covered in sentences such as:

-Thinker at your service

-Institute for theoretical art, universal poetry and outlook

-General secretariat for accuracy and for the soul

Everyone is welcome to enter the Denkerei and to present his or her question to its staff. I imagine that this employee then pulls a thick tome out of a heavy safe, leafs through and recites the answer, with a finger all the while pointing at the sentence at hand. But no, that’s not how it works. The Denkerei is no oracle, no storehouse of answers. This is where scientists, artists, politicians and writers come to think, reason, and discuss.

I try to open the front door. At first, it refuses to budge. It’s only when I lean against it with my entire weight that it opens. I step inside. The door swings shut. Street noises are far behind me. Is there a connection between the heaviness of a door and the weight of a place?

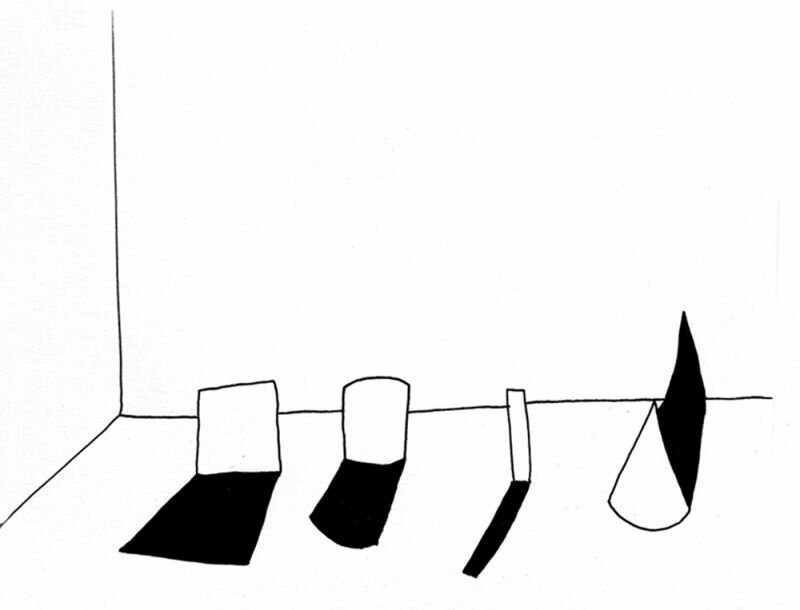

I find myself in a grand space, standing on a gleaming wooden floor that stretches over the entire surface of the building. Smooth white walls, a thin table occupied by a gigantic floral arrangement, chairs lined up on an empty stage, but also a sitting corner, and a bar above which lamps bearing the Denkerei logo emit a soft red light. Artworks are hung on the walls: painted panels that portray an intriguing play on perspective. This space is a cross between a waiting room, a gallery, and a hotel lobby.

At the table, a man sits behind a stack of newspapers. I recognise his face from the presentations I’ve seen on Youtube. It’s Bazon Brock: artist, dramatist, professor of aesthetics, and founder of the Denkerei. Through Wikipedia I found that he presents lectures while standing on his head and that he temporarily lived inside of a glass display case, but luckily now he’s simply sitting on a chair at a table.

“Anyone can walk in and ask a question”, Brock explains. If the question is interesting enough, the Denkerei will hold a symposium for it. Thinkers from different disciplines such as biology, geology, philosophy and medicine, but also from literature and the arts come together in order to explore the question and to utilise knowledge from these many different areas. All the while, thinking itself is sharpened. “Poets teach scientists how to think, and scientists teach poets how to ask questions”, Brock tells me. This doesn’t lead to ready-made answers: questions stay unanswered, even after a whole symposium is dedicated to it.

The Denkerei does not intend to find an answer, a quick fix nor a solution. The act of thinking is the main goal, which is not as simple as it may seem. “Learning to ask the right questions is essential” says Brock. You need to know which questions you’re asking and how to formulate them. We don’t learn this at school. Instead, we learn how to produce answers, which means that we often forget the nature of the questions that precede them.

In other words, the Denkerei does not supply answers nor does it bandage brooding brains. There is no intention to placate, like a visit to the doctor might: even though you might still feel ill or be in pain, you’ll feel better knowing you’re carrying an illegible prescription in your bag. A formulaic salvation that will rid you of your illness or pain, an answer to your question so that you’ll need not think further.

The Denkerei is far removed from anything of the sort. After twenty minutes of questioning Bazon Brock, I’ll leave this place with at least as many new questions.

“If you can formulate a good question, you’ll understand that an answer is also a question. An answer is a question in a different form.” After Brock has spoken this last sentence, he leads me to the door. Through the window I can see that despite the falling rain, the sun is shining.

Maybe questions exist precisely because there are answers.

Dorien de Wit's visit to the Denkerei in Berlin is part of her research into bringing art, science, and society closer to one another. This research was made possible through funding by the Amsterdam Foundation for the Arts (Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst).