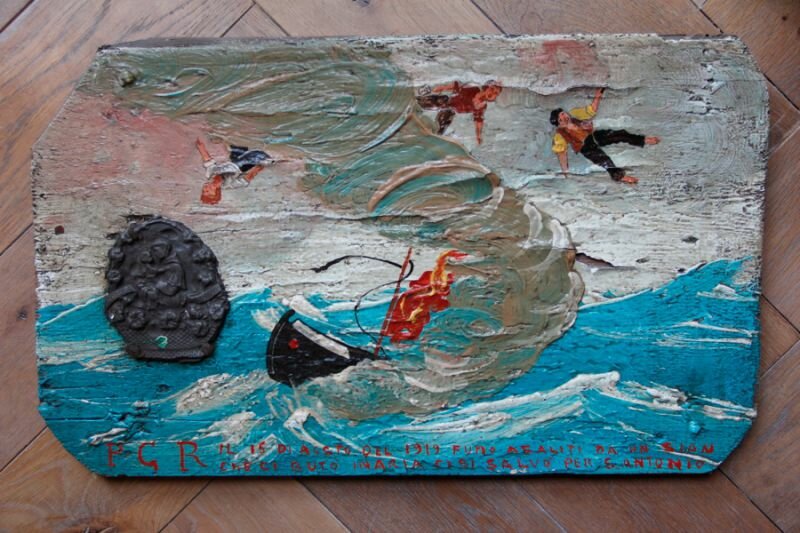

Mud flourishes where cold and warm meet. Travelling through the American Southwest state of New Mexico – in a time where adobe only referred to a local building technique involving sun dried clay – we arrived at El Santuario de Chimayo, a mud sanctuary. In a Spanish colonial church, Indians erected an altar behind a small, inscrutable hole: just lke Anish Kapoor’s hole at the Museum de Pont . But there’s one difference, the hole in Chimayo contained Holy Mud, as healing as the water of Lourdes. How this came to be? In 1810, a New Mexican friar discovered glowing earth on a hill.

He began to dig and found a crucifix that he brought the next village, Santa Cruz. But it disappeared from there three times, only to be found in the same old mud hole. The message was clear. The crucifix was to stay there. And thus, the chapel rose around it. It turned out that the mud was holy (not to be confused with Holy Mud, a Dutch chocolate mousse dessert) and healing. Crutches left abandoned at the wall of the church testify to the healing power of the sludge. On a miracle website I find a story of a girl who was cured of fifteen tumours in her leg after applying Holy Mud mixed with her own saliva. She’s now plays cello in a Philharmonic orchestra.

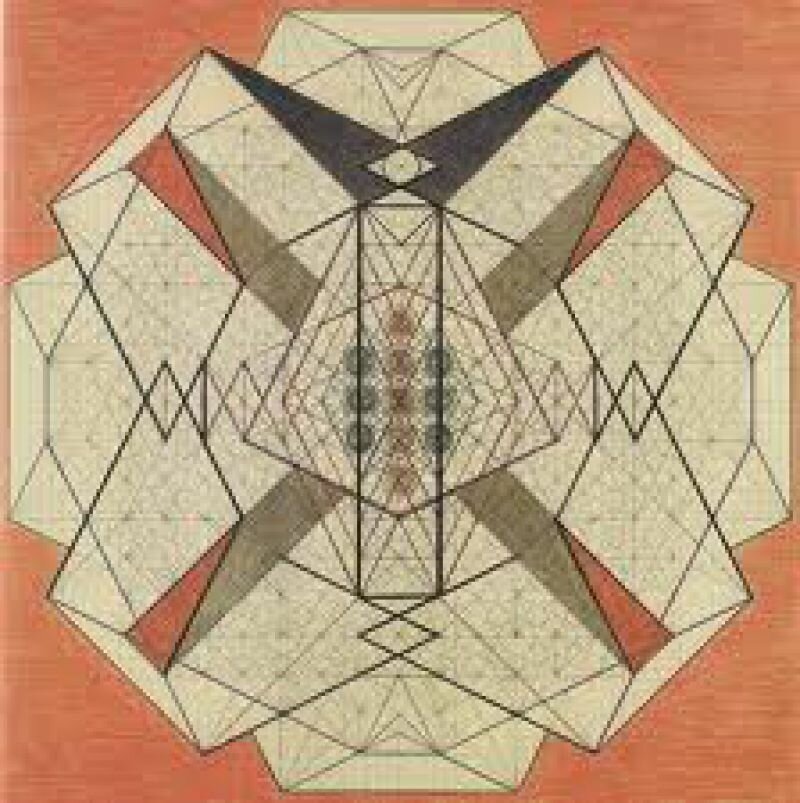

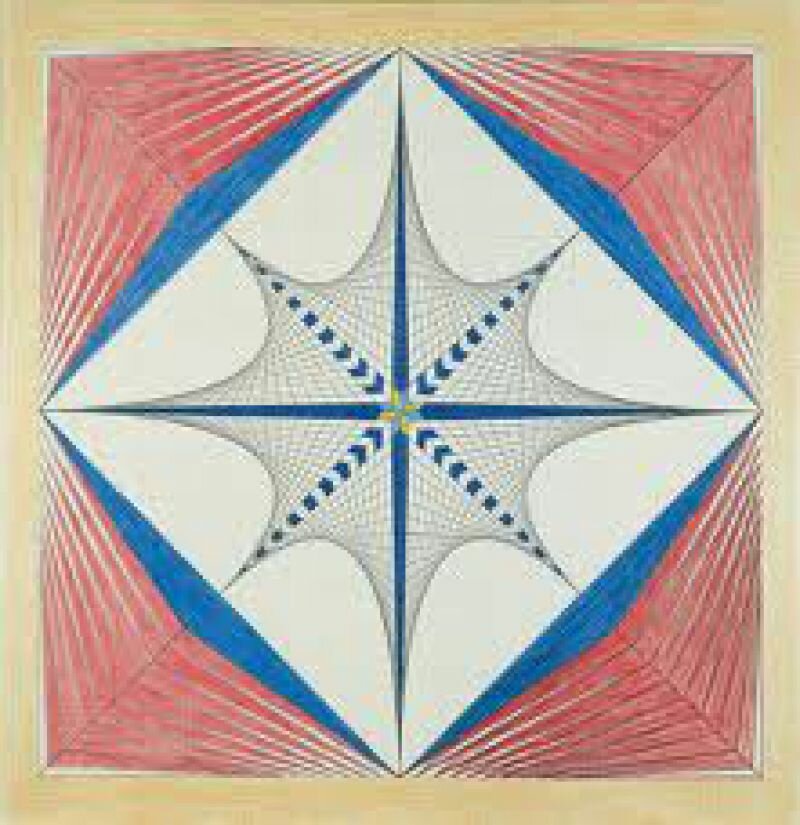

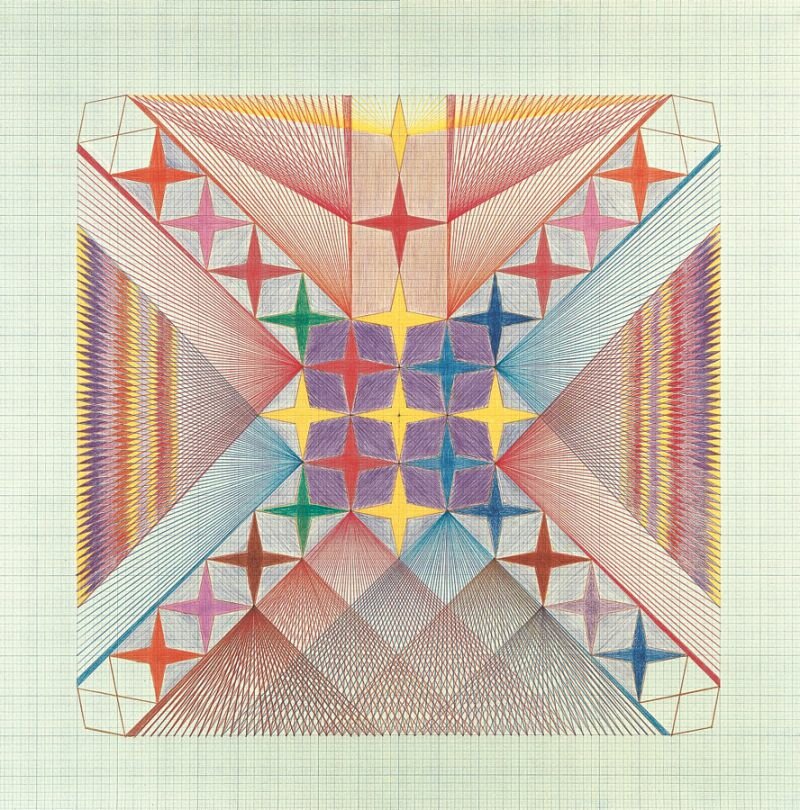

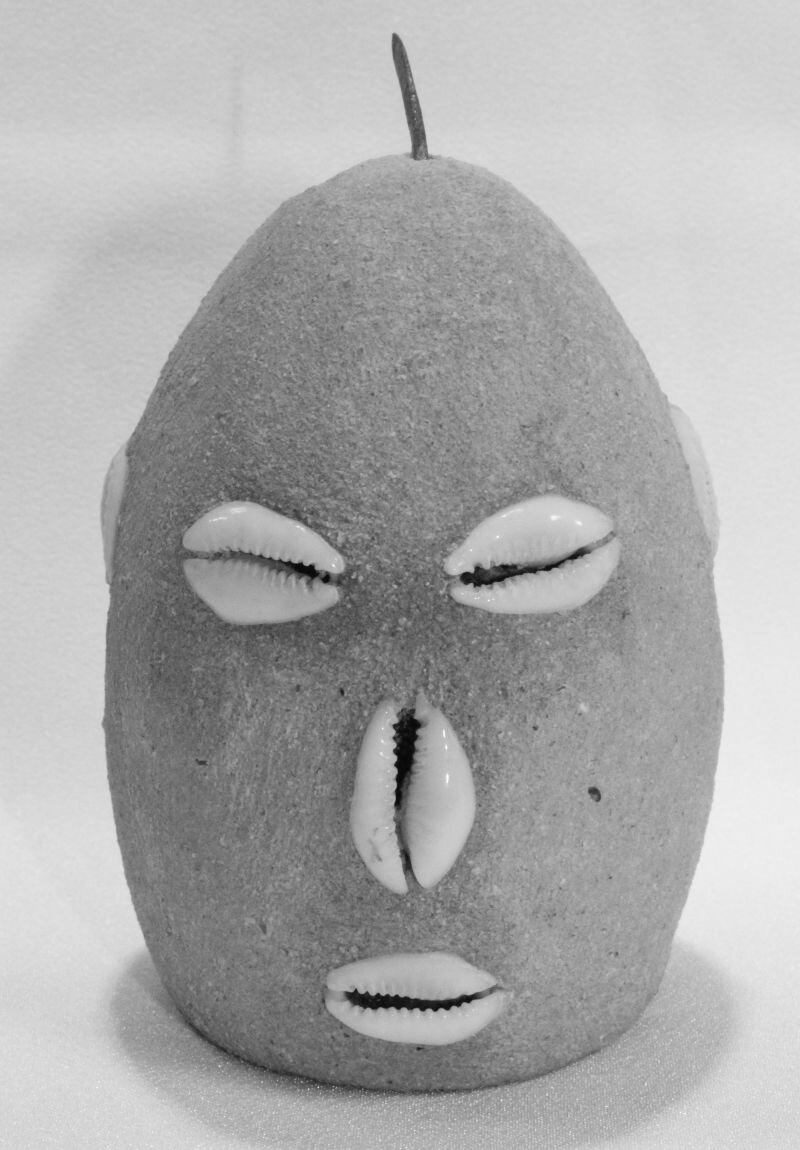

Mud seems to be the catalyst of transformation. In Vodou rituals, packets of clay and earth are made to influence events (like putting your nemesis on the wrong track, for example.) Eleggua is an egg-shaped pointed head formed from clay, with shells for eyes. The evil Humpty Dumpty is part of the Carribbean pantheon of Santeria and acts as the guard at (muddy) crossovers and mediates between the upper- and underworld.

Likewise, in other ancient tales of animism, an inferior being rises from the mud. A figure in the Jewish Kaballa is the Golem: a soulless, formless mass. During the 16th century, Rabbi Juda Löw ben Betsabel of Prague documented a number of Golem stories. Extremely holy persons in close proximity to God were given the wisdom and power to create life. But what they were able to create from mud remained a shadow of His Creation. After all, Golem, the mud figure, couldn’t speak. In later literary versions, the rabbi Rabbi Juda Löw is credited as having shaped Golem himself from the muddy banks of the Moldau. The creature would help the poor, similar to the robot that Karel Capek, also Czech, would later invent. Of course, his tale ended badly. This is where the Jewish idiom “olem golem” derives from: man is the golem, man is a machine. Or, in other words, the world is an evil place. In the latest postmodern, post-historical, post-religious incarnation, Golem is a malevolent turtle-like character in the Japanese game of Pokémon.