The guest room is situated somewhere in the outer regions of the house. Up two flights of stairs, the door on your right hand. Which is mostly closed.

The residents stay elsewhere in the house. Sometimes the door of the guestroom unlocks with a moan: for an unexpected guest. Who had missed his train. Or whose car broke down.

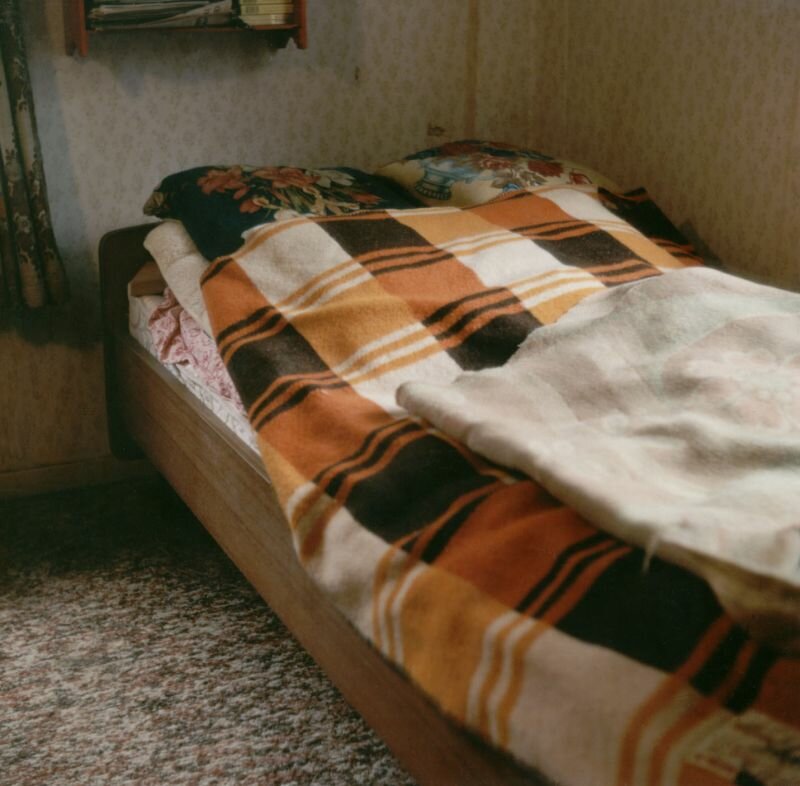

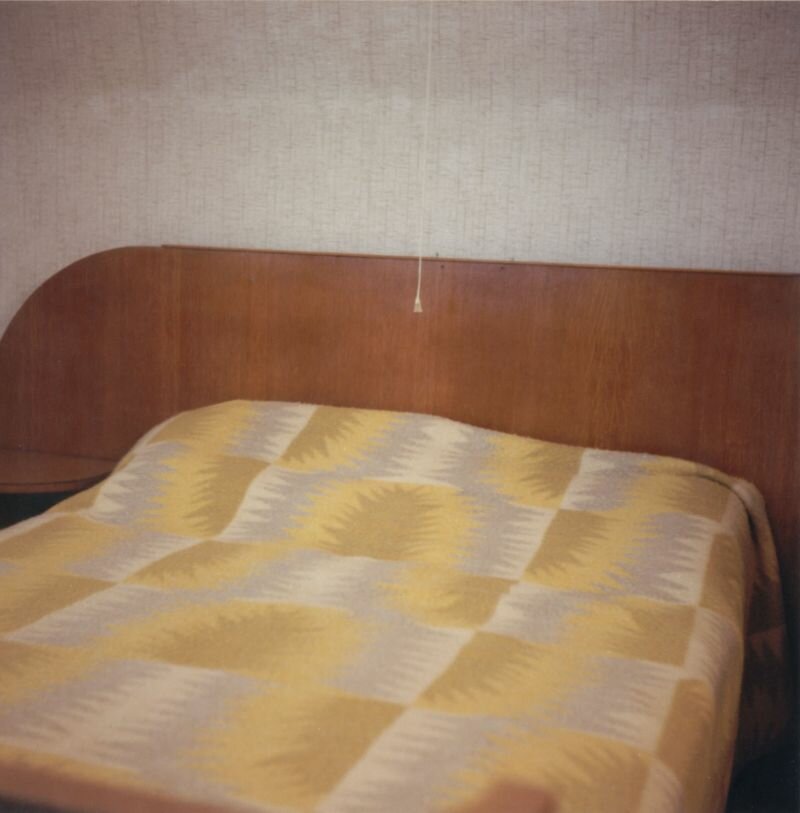

The guest for the night, having had a strenuous day’s journey – even if it lasted only a few hours – has one desire only: a bed to sleep in. With eyes shut, you can’t see where you’re sleeping anyway. Peculiar, that anachronistic hotchpotch of sheets, cover, pillow cases.

What does it matter that the vista is of a blind wall? Nothing indeed. No window whatsoever in the destitute corner, hammered shut underneath the rooftops? There’s a fan in case it gets too warm. Tomorrow starts early anyway, one will be right on one’s way.

Guest rooms harbour, except the grateful passenger, mainly good intentions that suggest hospitality. For the mattress has a cavity in it which makes sleeping less than great. Even after fourteen times from one’s left side to the right and back.

The metal spiral creaks meekly. It smells indistinctly. Of wet dogs, or half-decayed rubber rain coats. Something like that.

The guest who sleeps over feels himself lying in bed with all people who have spent the night in this guest room before.Lamps, furniture, walls show “the traces of years after a life full of worry and duty” (To paraphrase Gert Timmermans’ Reverence for Your Grey Hairs)

How many times mustn’t the metal foot of the bed have slammed against the once-sassy wallpaper for it to have acquired the look of a leper? And who or what caused those curious dents in the wall? (Your uncle Bert could be so hot-tempered sometimes.)

The grotesque, grey stain on the bed spread is probably from the German shepherd, who had to vomit so excessively back in 1982, before he had his injection. (Ah, how he used to love sleeping in the guest room.)

They don’t know, but like the guest, the furniture pieces too are merely passing through. Thirty years ago, their existence began as a show piece in the sitting room. It went downhill from there. They became dated and then, the ill-fated day came in which they had grown ripe to be parked in the guest room.

Call it sustainability, call it frugality. Sad it remains to see them there, with a dishevelled flair, in the limbo to the attic. Afterwards waits another, final destination: as refuse along the pavement. After all, the grandchildren, who move out on their own, disdain the stuff from grandma’s guest room. (IKEA is not that expensive.) The buyer, who takes the whole lot, doesn’t mind taking them with him to the municipal dump, as long as he gets paid.

It is not that far just yet. The guest room awaits and ages visibly, goes extinct. (There is a housing deficit. Residencies in The Netherlands are too small to keep rooms vacant. The country itself is small enough for you to drive back to your own bed in time.) One day, a wrecking ball will hit the façade, and walls and floors will collapse. Only the rear wall will stand for a brief spell. Somewhere, high up, the flowered wallpaper of the guest room will flutter in the wind.

(photo's: Dorien Boland graduated from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam with a photo series of guestrooms (direction of study: individual set of subjects).She has been invited to continue her studies at the department of photography at the post-academic course of the St. Joost Academy in Breda.)