We returned from our art trip to the north west of France feeling disappointed. What we had encountered were mainly echoes of Paris. Silently, we drove homewards. We felt let down, it certainly had rained on our parade.

It was in this state that we were confronted by the accident that would prove itself a gift from the gods; the sensation we’d been yearning for all that time.But let’s start from the beginning.

The first museum was in Rennes and it immediately set the tone for the remaining excursions. One or two of the worst works by big names, mainly French of course, were being exhibited. Granted, a bad work can be illuminating in reminding us that even a genius is but human. But after a number of these reminders we began to grow bored.

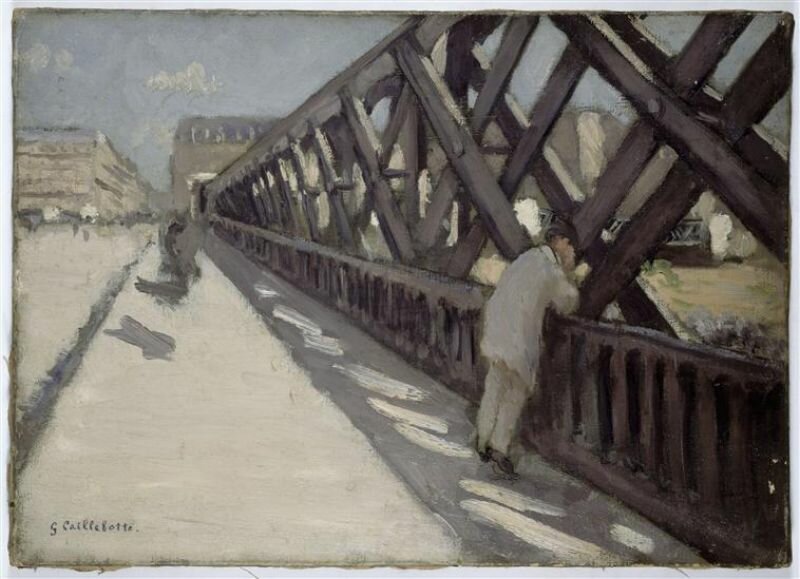

In Rennes our eagerness was still boundless, and so we dutifully shuffled from one painting to the next. Suddenly we pointed out one that was truly exquisite. Caillebotte, how beautifully he managed to render light in his painting! How he succeeded in creating such a grand effect with something as simple as the construction of a bridge and a man leaning over its railing!

We became increasingly lyrical and were beginning to exaggerate, and we stopped being able to properly look at the paintings. We no longer trusted our own judgement and decided to ask the invigilator for directions to the museum café.

There was no café at the museum of Rennes.

The same pattern repeated itself in Vannes. In the brochure Corot, Millet, Delacroix and even Goya were featured to lure the visitor. The thirteenth century judicial building transformed into a museum showed work by all these giants, with the exception of the Spaniard. He’d never even been there, they said. Handfuls of regional artists, on the other hand, had apparently frequented often, as the plethora of at times downright clumsy paintings attested to.

The most interesting anecdote was pertained to the painting by Delacroix. The pastor, whose church was to receive the painting, studied the work in his own room for weeks. He came to the conclusion that Maria Magdalena, the central figure in the work, was wearing a robe with an indecent décolleté. Like a ruthless restaurateur, he made his adjustments using thick black wall paint. The painting was then taken to the church tower to cover a drafty hole.

DELACROIX RESTORED

Goldreyer is of all ages we thought, and asked the way to the cafe. Once again, to no success.

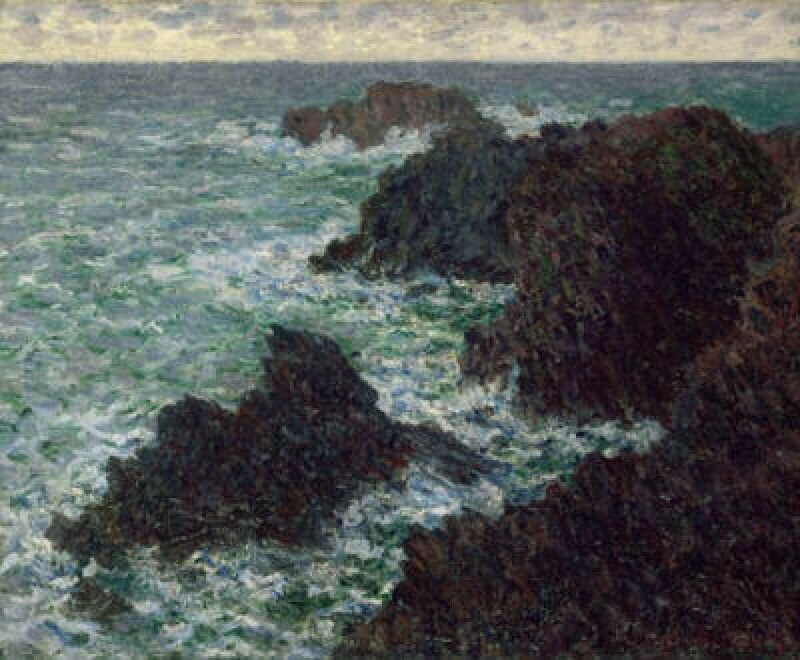

The museum in Nantes had a better, albeit equally obligatory collection. After seeing the two deplorable Monets and hearing that the museum cafe would “maybe be built” the following year, we gave up.

In the second building we came finally came across something that made an impression: a cryptic by Bill Viola. The three panels showed, respectively, a woman giving birth, a man under water, and a dying woman. We watched the newborn being brought into the world while the woman perished. We heard moaning and screaming, the bubbling of water, and the pumping of the life support machine.It was just what we needed—confrontational, yet at the same time soothing.

Where could we find more in this vein? Would it be better to simply go out into the world and cast our eyes onto harsh reality? In other words, onto life and death itself? All the to and fro in between only resulted in compromise, fabrications, art.

In the end, we drove home in silence, disgruntled by the inability of our stomachs to automatically communicate their richly filled contents to our brains. Then, on the N25 towards Arras, a two-lane road, we saw the horrific accident.

We trudged onwards. A car lay on its back in the curb, completely crushed. Two military officers strapped a man and a woman, both possibly dead and, in any case heavily bleeding, onto stretchers. The air was filled with shouting, lights were flashing all around. Men and women in white jackets hurried around the ambulance while the fire brigade hose the car. While one police officer filmed the scene, another urged us to keep moving.

At the very last moment we thought we noticed something strange. We saw the male victim laughing. Could it be possible that some people really do leave this world with a smile?

A few kilometres down the road we saw a large billboard on had only the letters ACF (Automobile-Club de France) written over it and the question: “Have you see an artwork recently?” “No,” we said out loud.

No?

We decided to leave the road as soon as we could and to take a back road to return to the site of the accident on the main road. It took us four hours to manoeuvre back, four hours to witness twenty seconds of something that might have been art.

It was an artwork. Everything was unchanged. The white coats were still running around, the victims still hadn’t been loaded into the ambulance, the policeman was still filming. This time we saw that on the side of the ambulance, a large reproduction of Gericault’s “The Raft of the Medusa” was printed. The military officers wore uniforms that corresponded exactly to the flute player on Manet’s famous painting. In the air above the scene, swirls and curls hung, unmistakeably like van Gogh. But we had to drive past straight away.

That day the television broadcasted news of the accident we’d seen.

Motorists were extremely upset. For hours, the roads had been hindered by absolute nonsense. Afterwards, the minister of transportation who had granted permission for the spectacle, claimed the uproar to be self-righteous. At least ninety percent of those passing the accident had no clue that the accident was a fake. A member of the artist collective responsible for the work asked himself why people weren’t relieved now that the victims were, in fact, healthy and well. “You operated under the name ACF,” the reporter said, “now the auto club is outraged.” “There’s nothing we can do about that,” was the answer, “l'Art se Conforme à la Folie. That’s what those letters mean to us. “

http://www.cornelbierens.nl/