Iona Hoogenberk is an artist with a classical background. She obtained a doctoral Greek and Latin languages & cultures at the Universiteit van Amsterdam and has been teacher at the Gymnasium Haganum. She graduated in 2010 at the KABK in The Hague and is member is the dispute Arktos (Amsterdam Studenten Corps).

I

Iona Hoogenberk

08.10.2013

There is a particular and usually unmistakable characteristic that certain objects, clothes, dishes, tools, and even words have in common: being self-made.

Alone or with others, one has decided to cast so much attention to a self-made thing so it forms a closer relationship to it’s maker than any other found, bought, or given object will. (Similairly, a self-formulated thought, formed with the same sort of attention, will take a more permanent hold in your head than a thought read and borrowed.) The French philosopher Bachelard touches upon this in his “Poetics of Space”: objects that are cherished achieve a higher degree of reality than objects that leave one indifferent.1 Self-made things are especially easy to cherish. They represent the loving attention of the mind and hands. That which leaves you cold does not exist. That which you cherish remains.

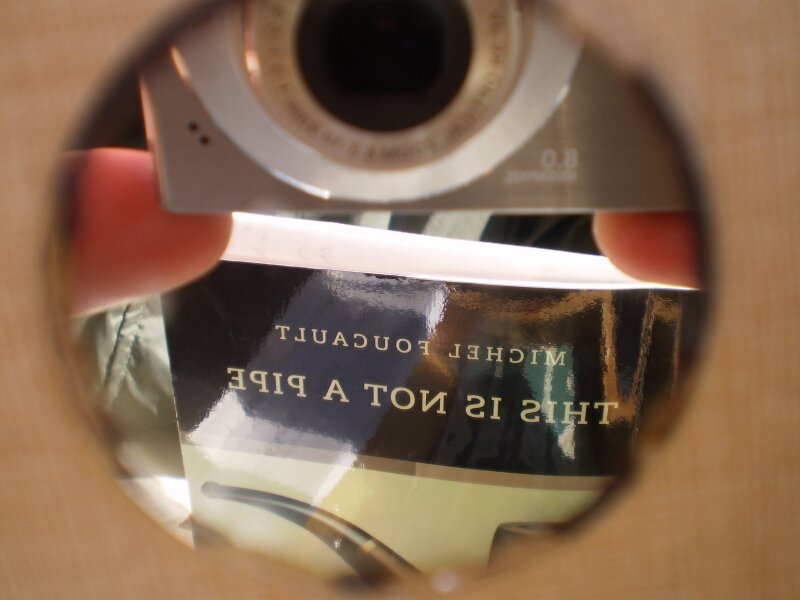

The amount of attention directed to a work determines value: a self-made photograph is dearer to you than a photograph you stumble upon in a book, despite the fact that, objectively seen, it’s a better photograph. For that same reason, a fire burning in the hearth is so very pleasing, because it requires more than just an automatic turn of a knob to heat the room.

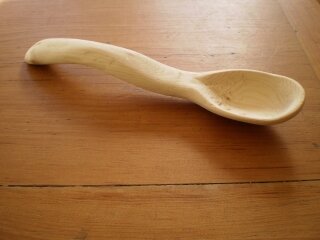

Compared to the endless ocean of the universe that surrounds us, even art is too small. Regardless, artists self-make with all their might, resulting in little islands. Joost Conijn (1971) for example, made his own wooden car fuelled by wood, and even flew his third self-made airplane to Africa. Iona Hoogenberk (1982, writer of this article) built a house by herself, small but real, existing for one night, only to break it down brick by brick, tile by tile, with the same attention as directed towards the construction of it. It was a sweet house, self-made and self-deconstructed. The unique combination of imperfections attributable to the self-made cannot be bought, and is charming. The self-made stool is comfortable, despite the crooked light; the apple pie is delicious, even if it’s undercooked. That which is not interchangeable becomes a part of you.

Like so many other things, the own experience here is the most important thing—and to gage subjective quality the degree of self-madeness is the best indicator.

1Bachelard, Gaston, The poetics of Space, The Classic Look at How We Experience Intimate Places, Boston (Mass): Beacon Press 1994 (1958), p. 68.