28.03.2015

04.03.2015

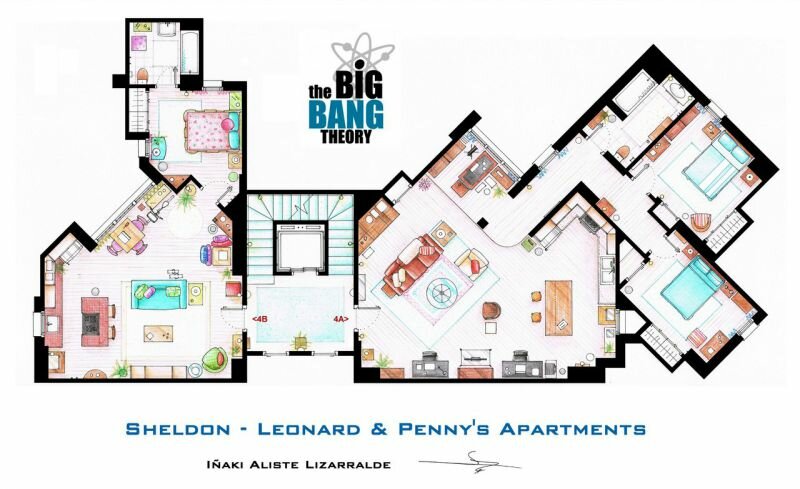

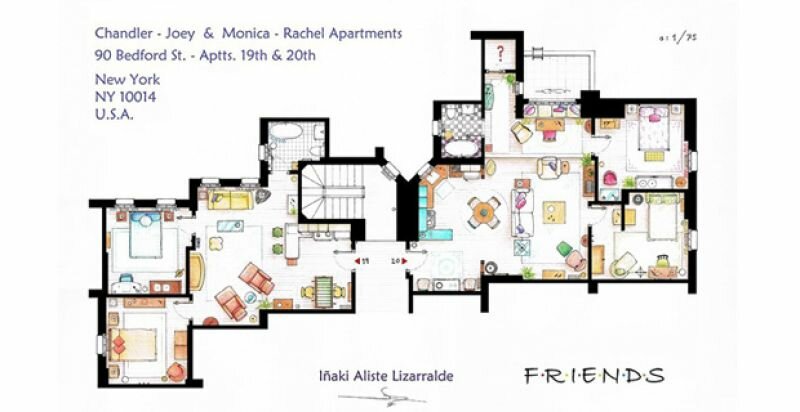

The Spanish interior architect Iñaki Aliste Lizarrald draws detailed maps of houses from TV series and films.

From Will & Grace to The Big Bang Theory to Up to Breakfast at Tiffany's: fans will instantly recognise the apartments they have so often taken a peek into. Lizarralde (42) meticulously studies the series to find out the precise location of furniture and the way the rooms are connected.

'About five years ago I started to draw the interior of Frasier's apartment,' he writes in an email from Azpeitia, a small town in the Spanish part of the Basque region. 'I liked the series and the apartment, which I wanted to analyse. Then a friend asked me if I could draw a map of Carrie's flat from Sex and the City. That's how this got under way.'

Lizarralde claims he isn’t a complete tube-addict. 'My own taste is somewhat old-fashioned: I like Six Feet Under, Upstairs/Downstairs and Twin Peaks.' However, in order to draw up a map he goes through each and every episode, finger on fast-forward, not to miss a glimpse of the interior.

'Episodes in which the houses are clearly brought into view I study extra carefully. The most important set, usually the living room, features in every episode, so that's easy. But rooms that are more rare to snatch a glimpse of are built anew each time someplace else in the TV studios. Similarly, interiors of houses in films are often hard to reconstruct, because in films they hardly ever show you the whole place.'

Since most series are shot in TV studios, the maps don't show squares or rectangles as in a regular house. 'Films are often shot in closed sets that resemble a normal house. TV series and sitcoms, on the other hand, are made using something like theatre sets,' the interior architect explains. 'The designers use tricks to make them seem bigger. That's why many maps are shaped more or less like a trapeze. Jerry Seinfeld's apartment, for instance, is actually tiny. Yet the angles of the walls are wider than ninety degrees to make space for the actors and the interior. Additionally, these angular rooms make the room look more dynamic.'

Lizzaralde neither tries to make them into normal houses, nor does he strive for a perfect rendition of the sets: 'I translate the aspect of theatre to the realm of architecture, that's where my interest lies.'

Meanwhile, the draughtsman has become unemployed ('for various reasons'), yet he uses his twenty years of experience in interior architecture to make the maps as truthful as possible. 'I know much about measurements and proportions. In the final drawing, everything must be right: the measurements and proportions, the furniture, the colours of the woodwork and even the location of the accessories.'

The final drawings are made with a felt pen, ink and crayon on coarse drawing board. 'I find that this method is peaceful. As an interior architect I used to make digital drawings too, but to these maps I wanted to lend that sense of warmth that only handmade drawings possess.'

It costs Lizarralde around thirty to forty hours to finish a drawing. He sells his work on Etsy.com. Then he copies the whole drawing, which costs him another ten to fifteen hours. And he isn't pricy: they change owners for just forty euros.

07.12.2014

I think the essence of life reveals itself in traces, in all the mistakes, the broken pieces we touch, the evidence of usage of things and surfaces, more so than in the successes we encounter in life. But what is the essence of the trace (if it has such a thing)?

For me, Barthes clarifies this through writing about the essence of a pair of pants: ‘What is the essence of a pair of pants (if it has such a thing)? Certainly not that crisp and well-pressed object to be found on department-store racks; rather, that clump of fabric on the floor, negligently dropped there when the boy stepped out of them, careless lazy, indifferent. The essence of an object has some relation with its destruction: not necessarily what remains after it has been used up, but what is thrown away as being of no use’[1]

The void comes to you as a revelation, it surprises, it amazes, sends you adrift into your own imagination. The void appears over time, through the accumulation of dust on a surface where a thing or an object is hanging, standing, lying. The trace appears only after taking the thing away. It is usually not made intentionally because it just appears on the spot where you hang your paintings, clocks, and shelves; place your furniture etc. The more time, dust, and light particles alter the surface area in terms of colour or appearance, the more the trace reveals itself.

The theft of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa in 1911 attracted an immense crowd of people from all over Europe, to visit and see the void in the place where the painting had hung before, [2] but not the thing itself since it was stolen. Thus the theft of the painting elevated its status even more. But what is the power, the driving force for wanting to visit the place, only to see the void? The void becomes the protagonist in the piece, but only because there once was a painting with a certain status. With the example of the Mona Lisa, it is obviously the status of the painting and the mental memory of the image that constitutes the status of the void.

The spatter is a joyful trace. It is like confetti on the surface. It shows itself mostly in the shape of little drops like little points on the surface. Sometimes they are gathered around a big central blot. Sometimes spatters looks like stars with a thicker centre part where thin lines depart from and stretch outwards. It can be created by throwing a glass of wine on the floor: where the wine will hit the ground, most of the liquid will strike, but around this centre there are tiny drops bouncing up again and falling a bit further off centre or touching a vertical other surface like a table leg or a wall. It resembles the fun of water, of playing. It is also joyful because it describes an instant, a moment that doesn’t last more than a second.

The waterfall, which only spatters at the bottom, is purely energy. The clashing of the water on the surface, the uncontrolled way the drops shoot through the air and land until they merge with the flat water’s surface. The same energy is visualized in the spatter trace, but then fixed on a ground. One moment of action is frozen and never able to repeat itself. Just as photography is the freezing of a moment, the death of the object, the still image where all the energy has been drained from, so the spatter a singular event: a moment fixed for just one time.

The smudge is the touch. It is distinctive because of its physicality. The smudge is, in essence, something you would make with your finger, hand or elbow or another piece of limb, together with some medium that makes it appear. This medium can be grains of powder, greasy substances, or anything that stands out on the surface that is being smudged.

Smudges are made by people; people with dirty hands, or dirty working clothes that fall on the floor. The smudge is always a human thing, the result of a directional action, like smudge traces you find on doors that are always touched on a certain spot near the edge of their surface on a height between approximately one and one and a half meters from the ground.

There is no trace without a past. It tells you that something has happened that took place at a moment in time before you see the trace itself. A trace can tell what has been on a surface, or for how long the surface has existed. A trace can reveal the inner layers of a surface, or show the most used places in a space. A trace can be made in an instant, like a coffee stain, or it can take years for a trace to develop, like the expansion of a wooden door.A trace shows time in itself.

This text is an excerpt from a full essay, to be read here.

[1]Barthes, Roland. The responsibility of forms, page 158, University of California Press, 1991

[2] Leader, Darian. Stealing the Mona Lisa – What art stops us from seeing, Faber & Faber, London, 2002.

This occurrence is the starting point for Darian Leader’s about why empty gallery spaces are attractive and why we like to look at art.

14.08.2014

Nearly everyone knows them: cuckoo clocks. That miniature house fastened to the wall, heavily decorated with leaves, birds, or other animals. Two iron weights, usually in the shape of pineapples, dangle beneath, and its wooden pendulum is most often covered in a leaf.

Children were – and are – especially fond of them. Time and time again, the little bird peeks out from behind the door to announce the time of day with its call, all the while opening and closing his beak, rocking to and fro, and sometimes even flapping his wings.

Although at one time the clocks were extremely fashionable, they gradually waned in popularity. They were generally considered increasingly kitsch and owning one became ‘not done’. The pinnacles of chic were the clocks from the Dutch areas of Friesland and the Zaan region, or otherwise the comptoises from France. In many cases, the cuckoo clock was exiled to the corridor, often ending up in the attic, and from there on, not seldom, into the rubbish bin!

But why kitsch? Even I have to admit that there are some very ugly specimens out there. The woodcarvings have become gradually less refined and the garish use of colours has become increasingly common. To my sentiment, the word ‘ugly’ is highly applicable in these cases. But to refer to them as kitsch? No.

When I think of kitsch, I think of all the so-called ‘old Dutch’ style Frisian and Zaanse clocks that have been widespread since the fifties and now ‘decorate’ the walls of elderly care homes in great numbers. These clocks can be classified as kitsch because they’re made up of parts from all over: with their multiplex or particleboard housing, their mechanics straight from the Black Forest, and their cast copper decorative elements emblazoned with the text: ‘Nu elck sijn sin’.

There is such a thing as an authentic Zaanse clock, but these are more than half a meter tall, its heavy pear shaped weight must be lifted twice a day, and it will set you back around ten thousand Euros. But then you’ll be the owner of a sample built in the 18th century!

Nowadays, most ‘experts’ assume that the cuckoo clock was ‘invented’ around 1730 by Franz Anton Ketterer in Schönwald in the Black Forest. Occasionally, the existing types of clocks of the period were fitted with two ‘organ pipes’ that held two small built-in bellows. Every half hour, a mechanism lifted these bellows in turn and since they differed in pitch the ‘cuckoo clock’ was born.

The famous house shaped cuckoo clock was not conceived until much later in around 1860. These clocks were modelled after the signal houses that had become a recent fixture along the railways crossing through the Black Forest, hence their nickname ‘Bahnhäusle’ among the inner circles. Although these early examples already were covered in woodcarvings, they were still relatively sober in execution. Increasing prosperity around the 1880s meant a boom in the variety in design and size. Some clocks were even provided with a second bird:the quail. He pops out every fifteen minutes and each hour he’ll chirp the time in the number displayed by the hour hands. Quite a few of the clocks are equipped with chimes. After the cuckoo’s call, a melody will play, like ‘Edelweiss’ or ‘Der fröhliche Wanderer’ or a snippet from Mozart’s ‘Eine kleine Nachtmusik’ to name a few examples.

Since the beginning of its inception, the cuckoo clock has kept up with each style of furniture: ‘Biedermeier cuckoo clocks’, extraordinary Jugendstil examples, clocks in Art Deco style, but also ‘modern’ sixties and seventies versions.

Nowadays, the clocks are often fitted with battery-operated mechanics, ‘decorative’ weights and ditto pendulum. The realistic sound of a chirping cuckoo is programmed onto a chip and played through a speaker in the clock. With this clock in mind, I can sympathise with those referring to the cuckoo clock as kitsch. But the cuckoo’s call has yet to be relinquished and, still, some half a million clocks are manufactured in their ‘place of birth’: the Schwarzwald in the south of Germany. And not, like many believe, in Switzerland or Austria!

01.03.2014

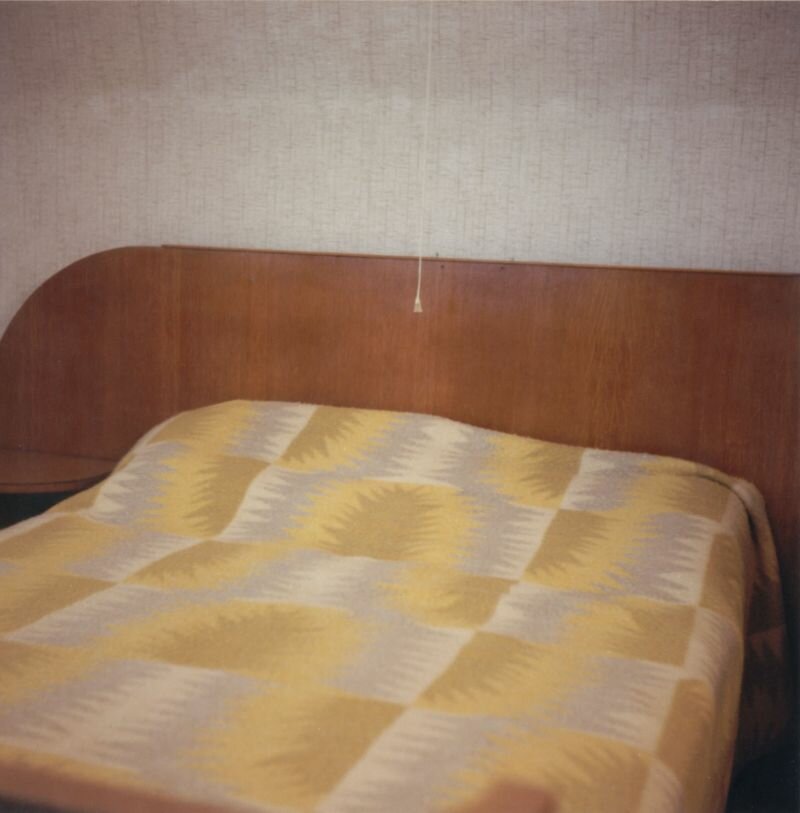

The guest room is situated somewhere in the outer regions of the house. Up two flights of stairs, the door on your right hand. Which is mostly closed.

The residents stay elsewhere in the house. Sometimes the door of the guestroom unlocks with a moan: for an unexpected guest. Who had missed his train. Or whose car broke down.

The guest for the night, having had a strenuous day’s journey – even if it lasted only a few hours – has one desire only: a bed to sleep in. With eyes shut, you can’t see where you’re sleeping anyway. Peculiar, that anachronistic hotchpotch of sheets, cover, pillow cases.

What does it matter that the vista is of a blind wall? Nothing indeed. No window whatsoever in the destitute corner, hammered shut underneath the rooftops? There’s a fan in case it gets too warm. Tomorrow starts early anyway, one will be right on one’s way.

Guest rooms harbour, except the grateful passenger, mainly good intentions that suggest hospitality. For the mattress has a cavity in it which makes sleeping less than great. Even after fourteen times from one’s left side to the right and back.

The metal spiral creaks meekly. It smells indistinctly. Of wet dogs, or half-decayed rubber rain coats. Something like that.

The guest who sleeps over feels himself lying in bed with all people who have spent the night in this guest room before.Lamps, furniture, walls show “the traces of years after a life full of worry and duty” (To paraphrase Gert Timmermans’ Reverence for Your Grey Hairs)

How many times mustn’t the metal foot of the bed have slammed against the once-sassy wallpaper for it to have acquired the look of a leper? And who or what caused those curious dents in the wall? (Your uncle Bert could be so hot-tempered sometimes.)

The grotesque, grey stain on the bed spread is probably from the German shepherd, who had to vomit so excessively back in 1982, before he had his injection. (Ah, how he used to love sleeping in the guest room.)

They don’t know, but like the guest, the furniture pieces too are merely passing through. Thirty years ago, their existence began as a show piece in the sitting room. It went downhill from there. They became dated and then, the ill-fated day came in which they had grown ripe to be parked in the guest room.

Call it sustainability, call it frugality. Sad it remains to see them there, with a dishevelled flair, in the limbo to the attic. Afterwards waits another, final destination: as refuse along the pavement. After all, the grandchildren, who move out on their own, disdain the stuff from grandma’s guest room. (IKEA is not that expensive.) The buyer, who takes the whole lot, doesn’t mind taking them with him to the municipal dump, as long as he gets paid.

It is not that far just yet. The guest room awaits and ages visibly, goes extinct. (There is a housing deficit. Residencies in The Netherlands are too small to keep rooms vacant. The country itself is small enough for you to drive back to your own bed in time.) One day, a wrecking ball will hit the façade, and walls and floors will collapse. Only the rear wall will stand for a brief spell. Somewhere, high up, the flowered wallpaper of the guest room will flutter in the wind.

(photo's: Dorien Boland graduated from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy in Amsterdam with a photo series of guestrooms (direction of study: individual set of subjects).She has been invited to continue her studies at the department of photography at the post-academic course of the St. Joost Academy in Breda.)