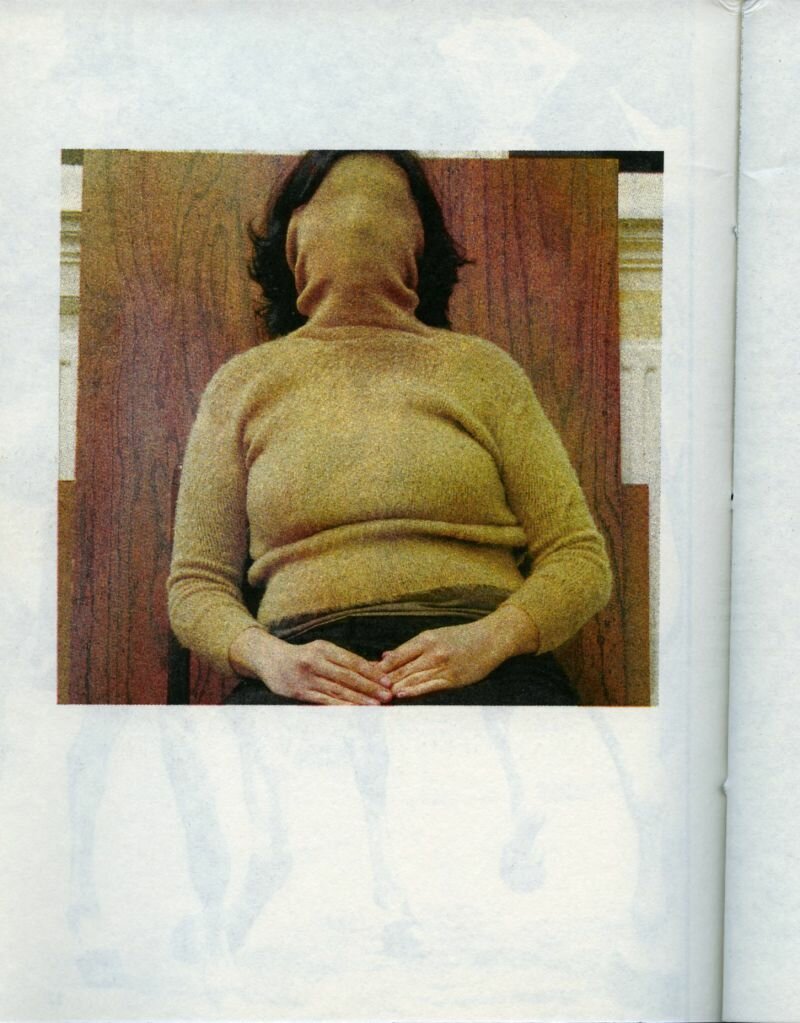

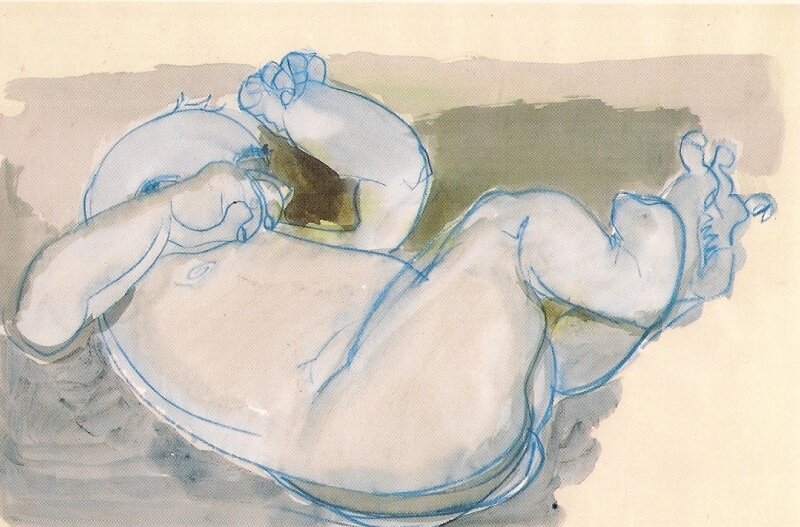

It is relatively simple to ascertain that all our knowledge of the world, including the most advanced natural scientific knowledge, is a product of both our perceptions and actions. The enormous conceptual step that we take in the cradle when we realise that some of the things floating in sight are our own hands, is retaken every time we understand something for the first time- albeit at a much smaller and less awe-inspiring scale. Our belief that the existence of our hands is an objective fact is the product of a very precise fine-tuning between several perceptions and the combining force of the mind. For those who then consider their hands as the ultimate instrument to verify the world's reality (to the extent that it is tangible), it might well be advisable to realise that there has been a moment when their minds composed their own hands from a confusing multitude of impressions.

When my daughter Julia was four years old she found a small compass in a desk drawer; she attached a string to it, wore it like a necklace and looked at it all the time. My father came to visit and complimented her on the beautiful compass. With a dignified air she said: "No grandfather, that is my alarm clock. How silly, this afternoon the shopkeeper also thought it was a compass." I realised that for a four-year-old, for whom hours and cardinal directions are hardly well known quantities, the difference between a compass and an alarm clock is not relevant. They are both round objects with a little clocklike face behind glass. The adult who corrects such a 'mistake' without being willing to explain the concepts of time, the four directions of the wind, magnetism, elasticity etc., has been led astray from the path of pedagogy. (In fact, it is not a correction but instead an innocent compliment.)

For a child, concepts and words are set apart by immeasurably vast blanks in the universe of impressions. On the best television show I know, Achterwerk in de Kast (Buttocks in the Closet), once a boy appeared who explained gloomily: "I find that life becomes increasingly complex: I used to think that the wind just blows, but now it turns out that the wind always blows from a high-pressure area to a low-pressure area." This boy is one among many individuals whose personal and adventurous relation to knowledge ends in school. The tragedy consists in the teacher's inability to convey the immensity of he high-pressure to the student, probably because he doesn't sense it either. The term 'high-pressure area' is not introduced at this point to open the door to an endless amount of new observations, but to erect a wall that effectively renders inaccessible the mysterious cause of the wind, of which every child naturally feels the global might.

Air pressure is a phenomenon for which we can educate and refine our observations. Semiconsciously, we perceive the way in which air pressure (and its connectedness to the temperature and humidity of the air) affects our bodily sensations and our general mood. If at school we would be taught, using a combination of theory and practice, how there is a direct correlation between these subtle air pressure differences on the one hand, and the pressure in the higher atmosphere causing wind to gather there amounting to hurricane force, on the other- well, this knowledge would not make us glum or disillusioned.

Our concepts form a network that, in proportion to the intricacy of its meshwork, is able to capture impressions in our consciousness; the rest slips through. But just as much as it is impossible to maintain an impression in the conscious mind without a certain degree of understanding, it is likewise impossible for a word or concept to be remembered if it does not become perceptible in one way or another. If this simple axiom of knowledge is overlooked, it leads to the erratic and depressing notion that our capacity for sense perception, or our thought, or both, are bound by an external limit. Our conceptual network has a horizon, just like our sense perceptions, and the two are interconnected. New impressions can only cling on to the fringe of our already-understood experiences; new concepts can only start off where existing ones had left off. To assert that behind these horizons, there is nothing, is about as short-sighted as the claim that what exists beyond them is the only true reality.

There is a vital connection between the fineness of our conceptual mesh and the precision of our observations. A good car mechanic can tell by the sound of a running engine what the matter is. That is not because he has better ears that the rest of us, but because his profession has provided him with a most distinguished insight in the parts, materials, movements, frictions and potential defects of a car engine. A chef is able to taste which ingredients are used in a certain dish, his "educated taste" consists of the amount of terms that during his career, he has learnt to employ to distinguish between all the nuances picked up by his nose and taste buds. Concepts cut up experience, which had at first instance seemed like a unity. Concepts bring to the surface what had been hidden in the depths of perception. Coarse concepts keep perception imprisoned in dark, dough-like creases, whereas real knowledge unfolds perception to form a great, illuminated plane.

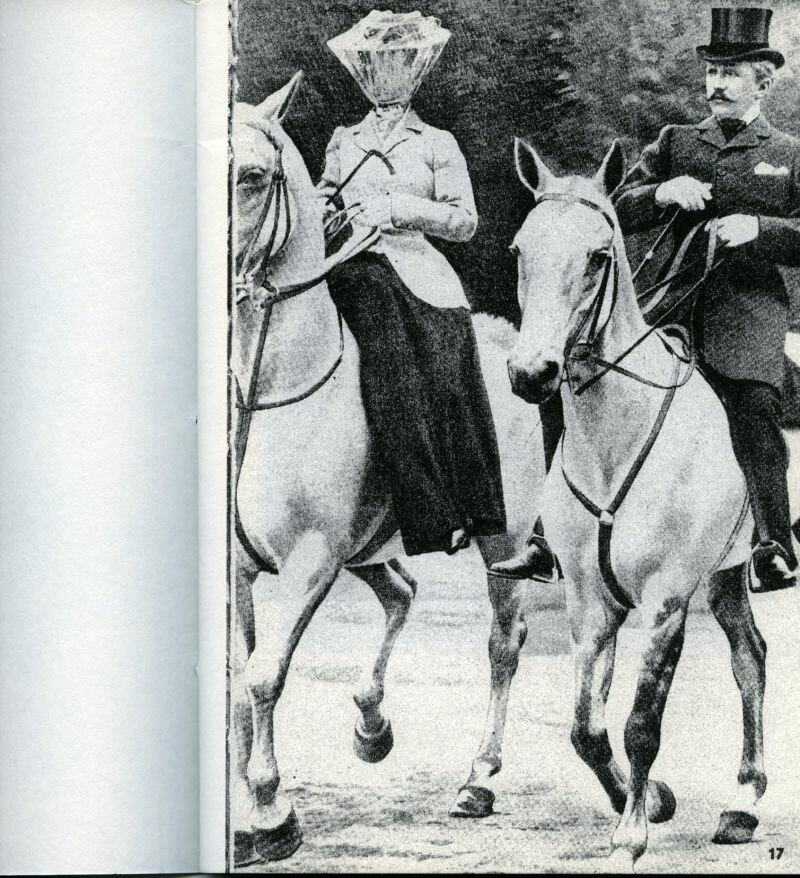

Art can make the experimental treatment of knowledge as practised by children urgent once more. When it comes to art, the aim is not to make something that is 'true' but rather something that looks convincing, which means that we play a cunning game with the regularities of the perceptible that has a twofold effect on the viewer: on the one hand he must be taken in by what he sees; on the other, he must remain continuously aware of the artificiality of the situation. The tension between the surrender to the senses and the feeling of complicity in the game is the liberating and consoling power of art.

In the human consciousness, a rift emerges between the world and ourselves. In our thought, we then mend this split in an ongoing process in which new observations and new names are woven together more and more closely. The liveliness of thought is of importance. Perception and thought, or the process of truth, provide independence and liberty.