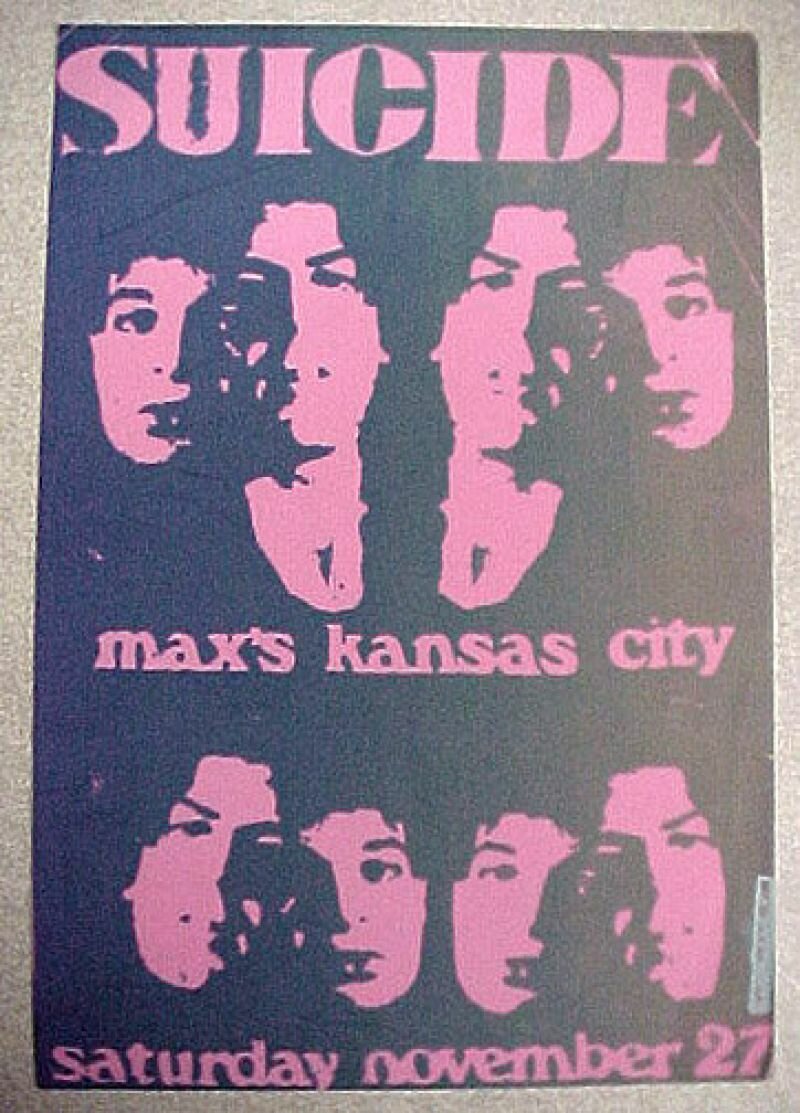

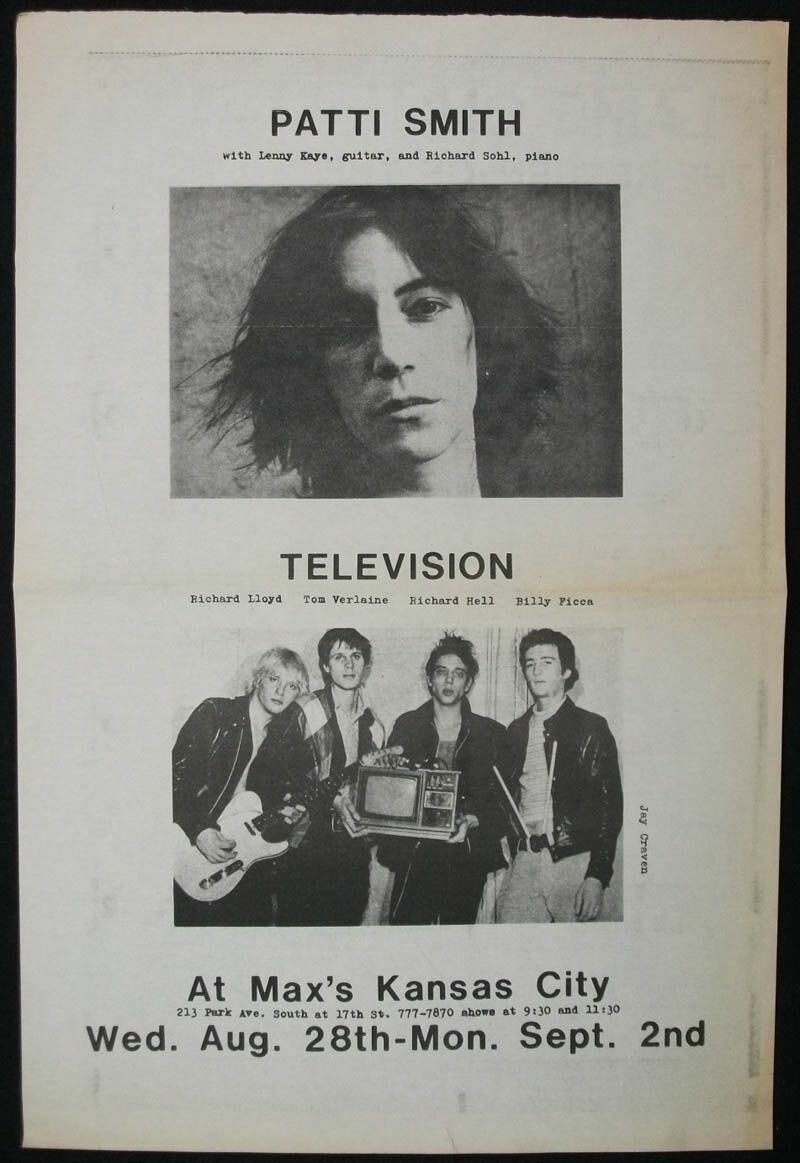

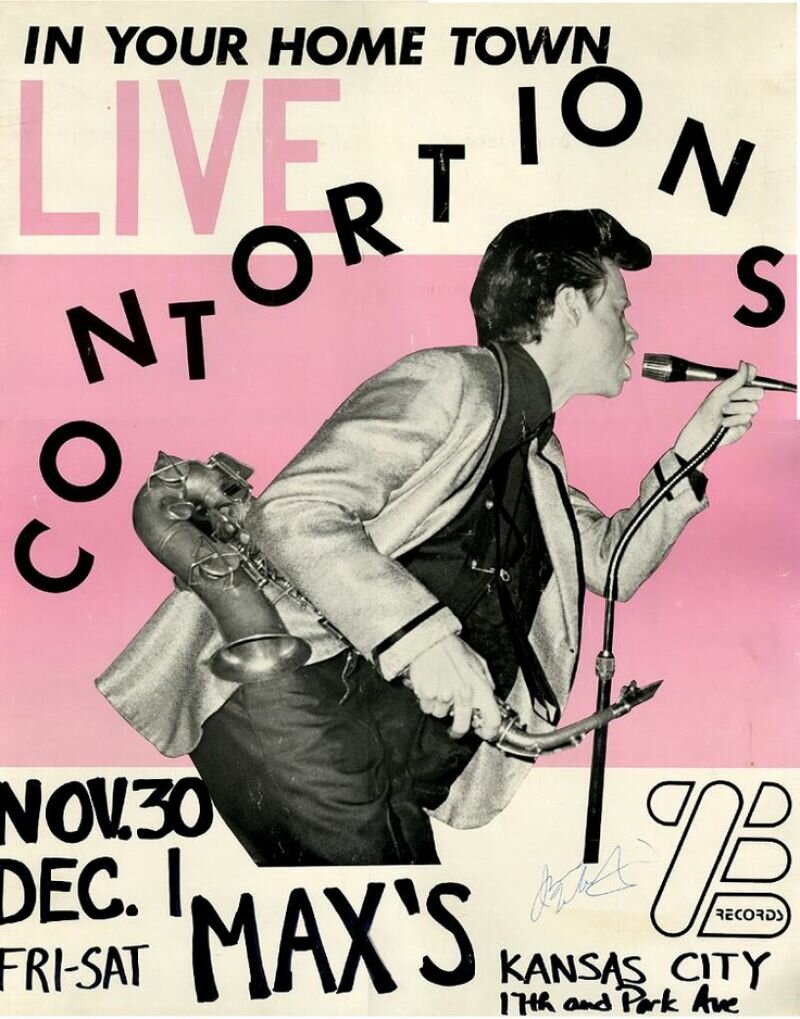

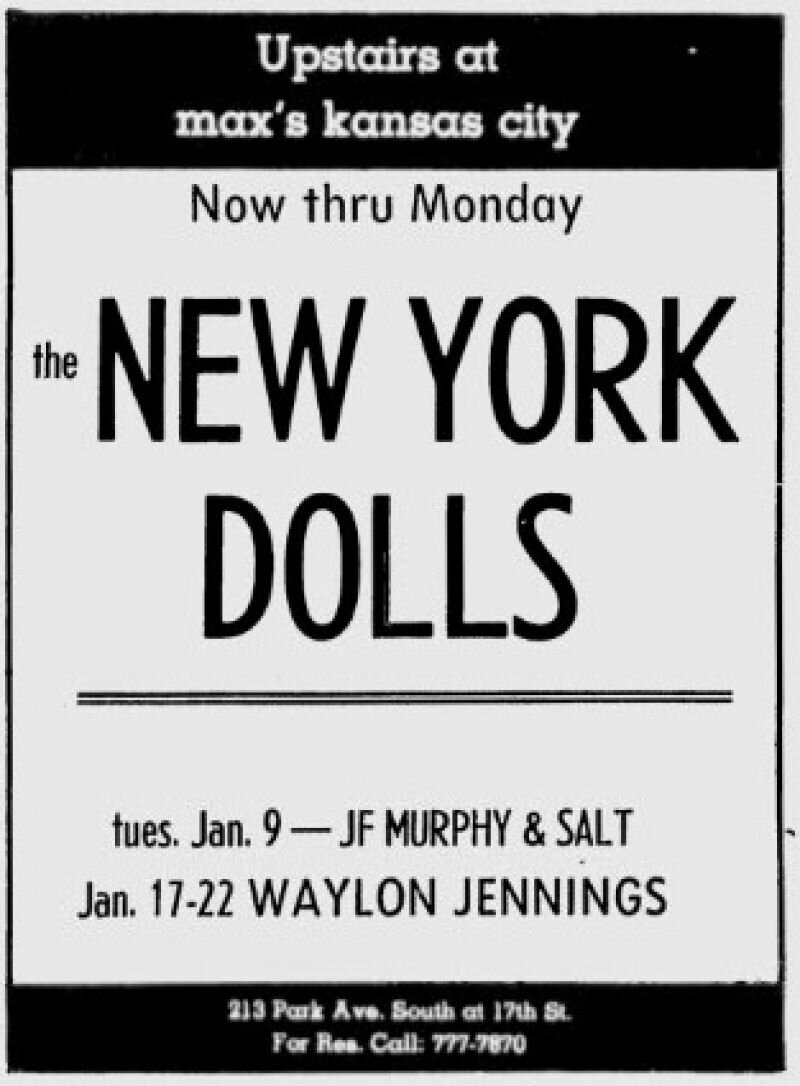

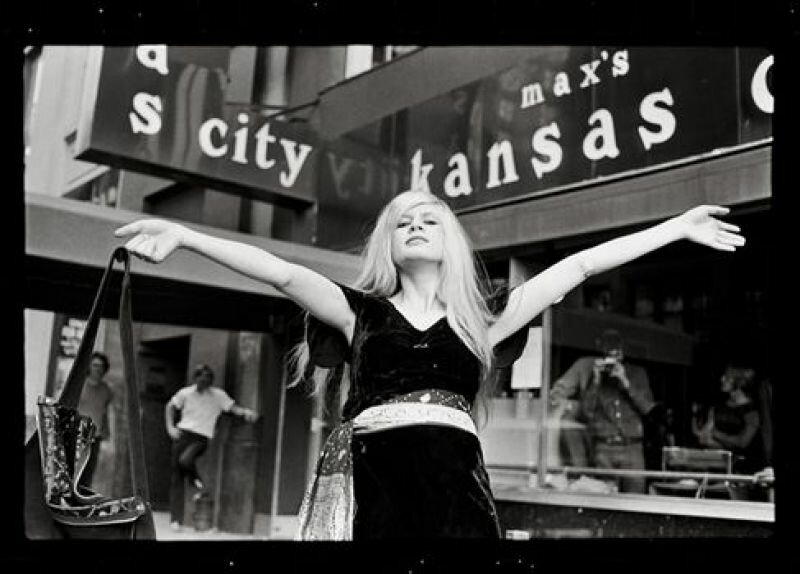

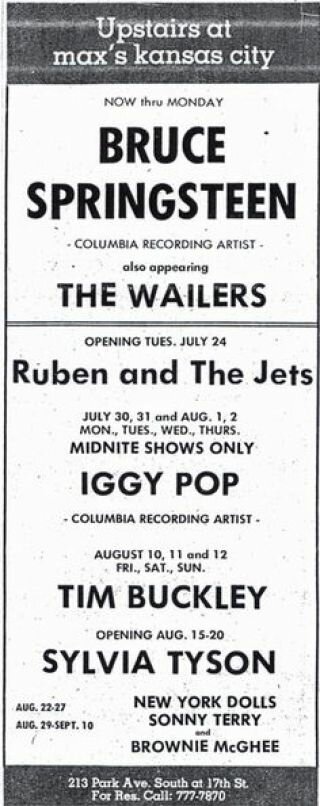

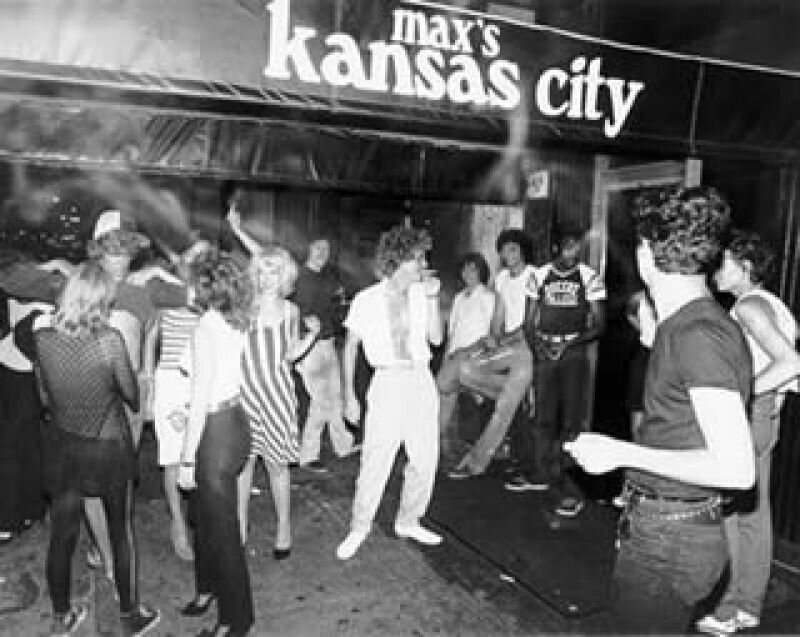

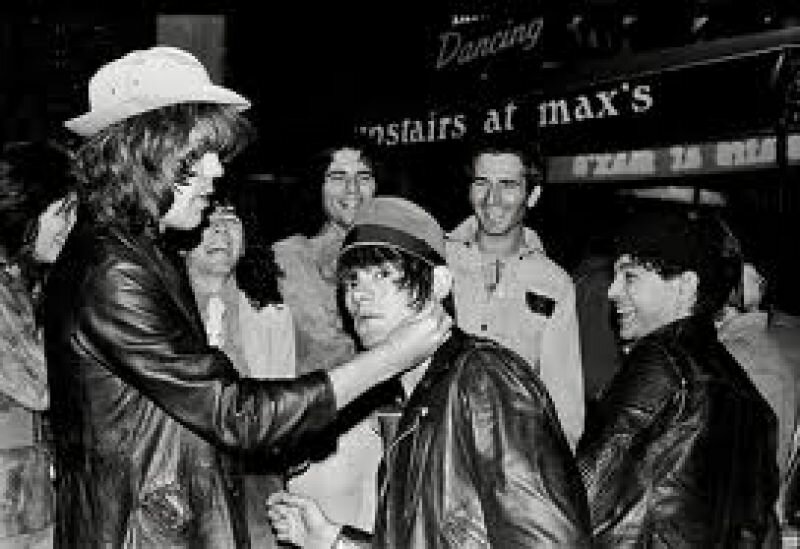

I met an art critic, a man well into his seventies, who told me of New York in the late sixties and of Max’s Kansas City: an unreal sort of meeting place where you could glance over the Velvets, William S. Burroughs, Stanley Kubrick, Janis Joplin, Dan Flavin, Mick Jagger, Bob Dylan, Dennis Hopper… the list is mind boggling and seemingly endless.

Critical art writers typically deal with resistance along the way and this critic, too, at times met with the steely glances of slightly scorned artists. But walking into the bar with the bulky Robert Smithson would make him feel a little bit safer from the evil eyes cast by the glamorous Warholians at the back, and from the sneers thrown his way by the Abstract Expressionists between their heavy discussions.

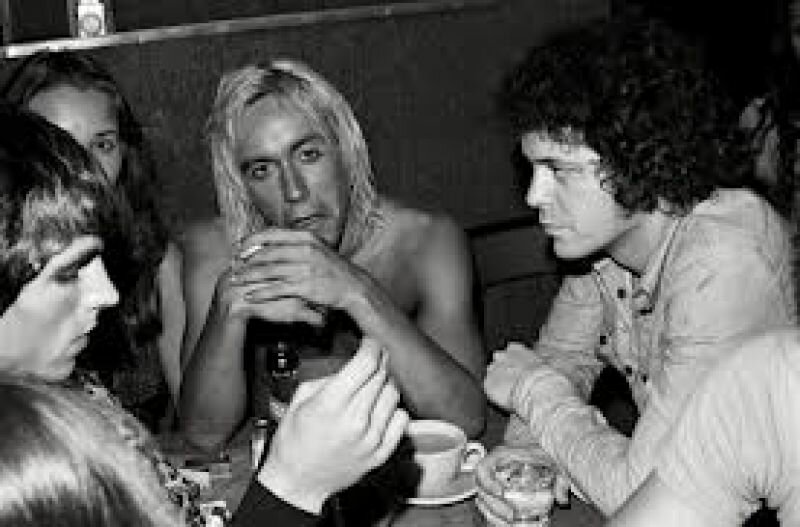

"I met Iggy Pop at Max's Kansas City in 1970 or 1971," recalled David Bowie. "Me, Iggy and Lou Reed at one table with absolutely nothing to say to each other, just looking at each other's eye makeup."

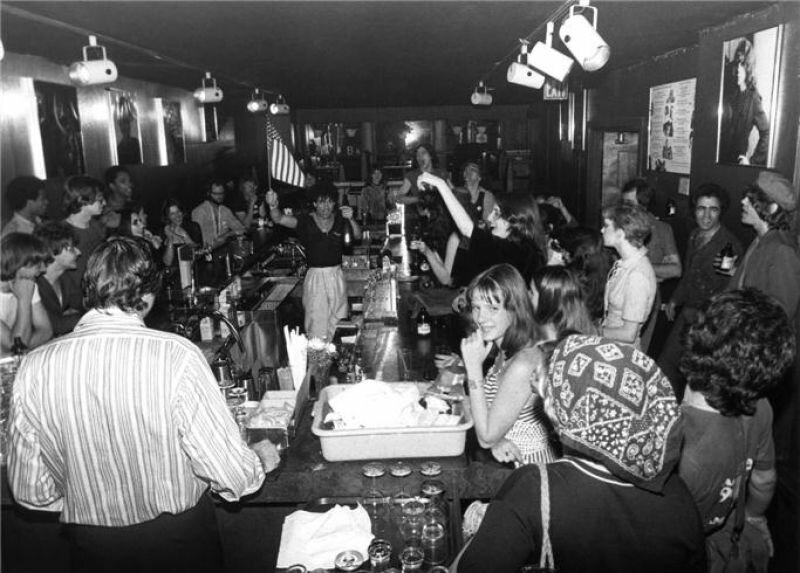

Myra Friedman, visitor to the bar explains:

Max's was a lot more than a magnet for sex, games, and drugs. It was an earthy, invigorating hangout, and the people who Mickey let stay there for hours and hours were definitely a breed apart, when being "apart" had real meaning in the world. I remember it for lots of conversation with lots of people who had lots and lots to say, and looking back on it now, the hum of the place strikes me as sort of the last hurrah of a genuine American bohemia. Like a great piece of writing, it was airborne from the minute it opened. It had beautiful wings; it soared.

It won’t come as a surprise that many of Max’s visitors had trouble paying their tabs. And in the typical artist’s tradition, they often paid their debts with artworks. Mickey was so eager to surround himself with artists, musicians, and writers, that he would allow them to spend thousands of dollars worth of food and drinks. A few beers in exchange for a Carl Andre? Doesn’t sound like a bad deal at all for Mickey.