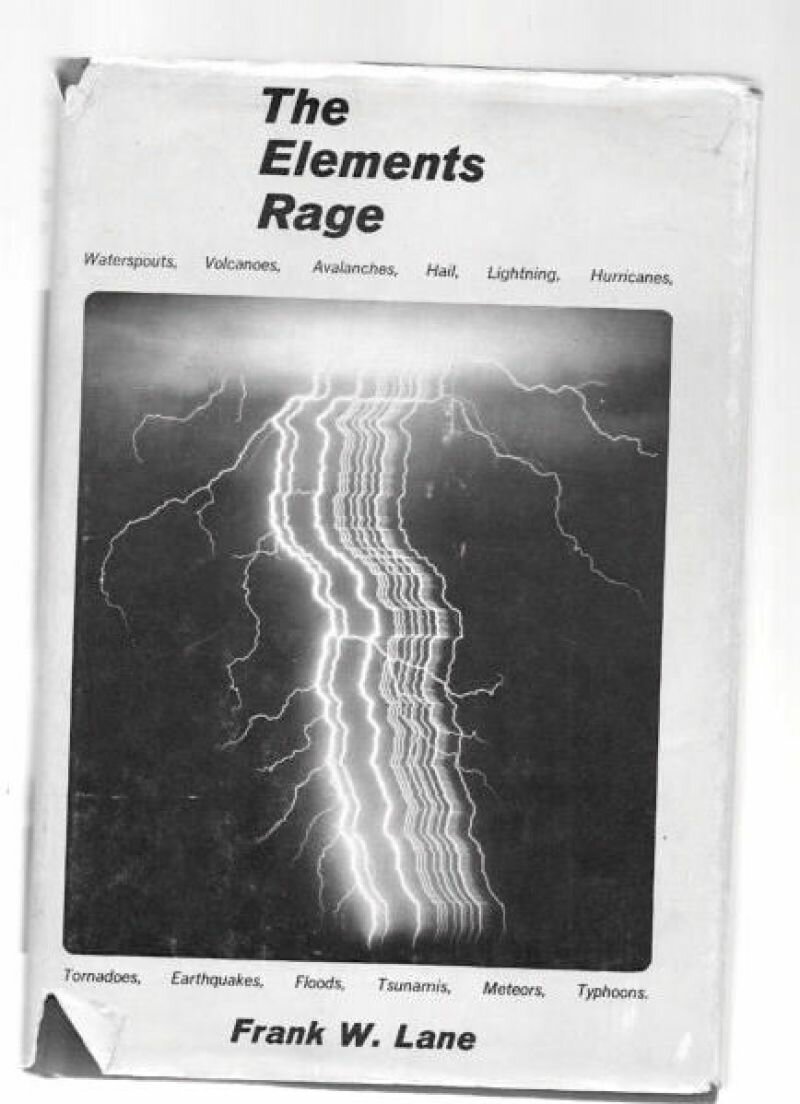

Was it W.G. Sebald who advised the budding writer to observe the weather and describe it in detail, preferably every day, as an exercise in perception? As a means to get a grip on the atmosphere of a narrative? I glide into the next page describing the processes that create lightning, "perhaps the most peculiar is ball lightning, a fiery sphere of light outlined by a hazy contour, that follows an erratic and slow path through the skies. It typically causes no damage, not by electric shock nor through heat. But it is typically unpredictable and can disappear as swiftly as it appears.”

The forces of nature as the fierce creator of volatile, elusive sculptures that leave no one untouched. Her works disturb, seduce, are never vain, lazy, or frightened. When necessary she will destroy everything, including her own oeuvre, to make way for a rigorous transformation that will changes the status quo.

In the meantime, I move through unfamiliar territory. In the corner of my eye, I catch sight of a video titled Mother Earth Network, Mysterious Holes. When I open the fragment, I see a woman seated at a rickety kitchen table in Guatemala city. She introduces herself as Inocenta Hernandez. Two TV journalists lean against her refrigerator. They ask her what exactly happened that night, there, under her bed. And did she knew she was living on the brink of a precipice?

Inocenta begins to tell her story: ‘There was a loud bang that awoke the whole street. People were walking around in their pyjamas in shock. Street dogs were growling. A boy was crying, he was naked. We thought it was a gas explosion at my place. I looked around my entire house but could find nothing unusual. When it was almost morning, I fell asleep feeling exhausted. The sun had already passed over the living room when I woke up. I stood up and spotted a shadow I’d never seen before, creeping out from underneath the bed. When I pushed the dresser aside, I thought my heart would stop: there it was! Oh, mother, mother! You nearly had me, you nearly swallowed me whole!”

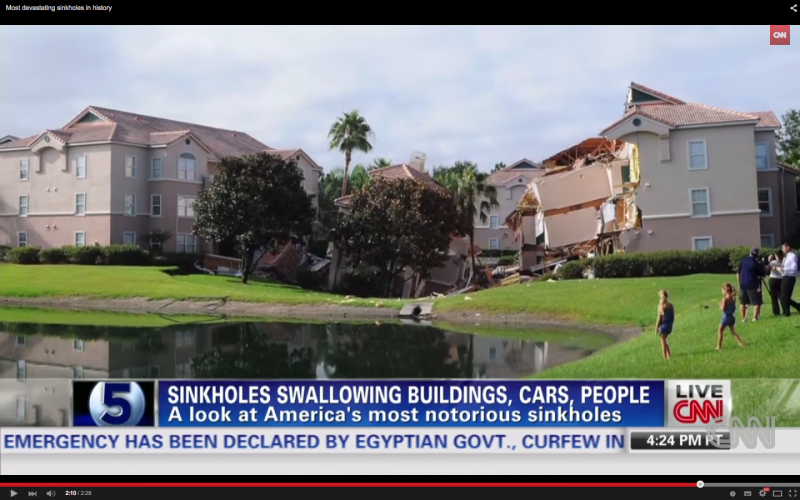

Slowly, the camera pans away from her, and I follow the reporter to the bedroom where he’s confronted by a hole of approximately one metre wide and twelve metres deep. The man casts an intense gaze towards me and assures me that the inhabitant is incredibly lucky to not have tumbled into the gash torn into the ground. The fathomless hole is filmed. I see nothing, he continues to speak. “The city is plagued by spontaneous depressions in the landscape. These geological phenomena, also known as sinkholes, black holes, and disappearance holes result from natural erosion, which can occur gradually but can also happen abruptly and out of nowhere. Guatemala City, built on volcanic deposits, suffers from leaking sewers and heavy rainfall, making it prone to ruptures. During a short period of time, three-story buildings, homes, trucks, flower stalls, and people have disappeared from our streets without warning swallowed by the shuddering earth.”

I now stumble upon sink hole stories everywhere and examine them:

Swallowing houses, cars and people

Drama as bus sinks into crater

America’s most notorious sinkholes

Seoul couple disappears in freak hole

Sinking fast

Horse vanished down under

Ticking time bomb under N.M. Town

Girls fall into sidewalk

The house just fell through

It’s a dangerous world out there, and I just can’t get enough. Another one, then. In the swamps of the Bayou Corne in Louisiana I’m witness to a number of scraggly old cypress trees being swallowed by an underground lake at Peigneur. I follow them until I see their tree tops slowly disappear into the water. These slowly falling trees move me. The destructive power of the sink hole elicits a surreal sense of delight. They remind me of the possibility of spontaneously falling into darkness. That the ground that I walk upon is of a capricious nature. ’There’s no solid ground’, artist Louwrien Wijers told me recently when I asked her about the importance of mobility: “We have to learn to live with groundlessness.” Stay dangerous, elements, keeping hitting your head and find your way to the ground via the heart.