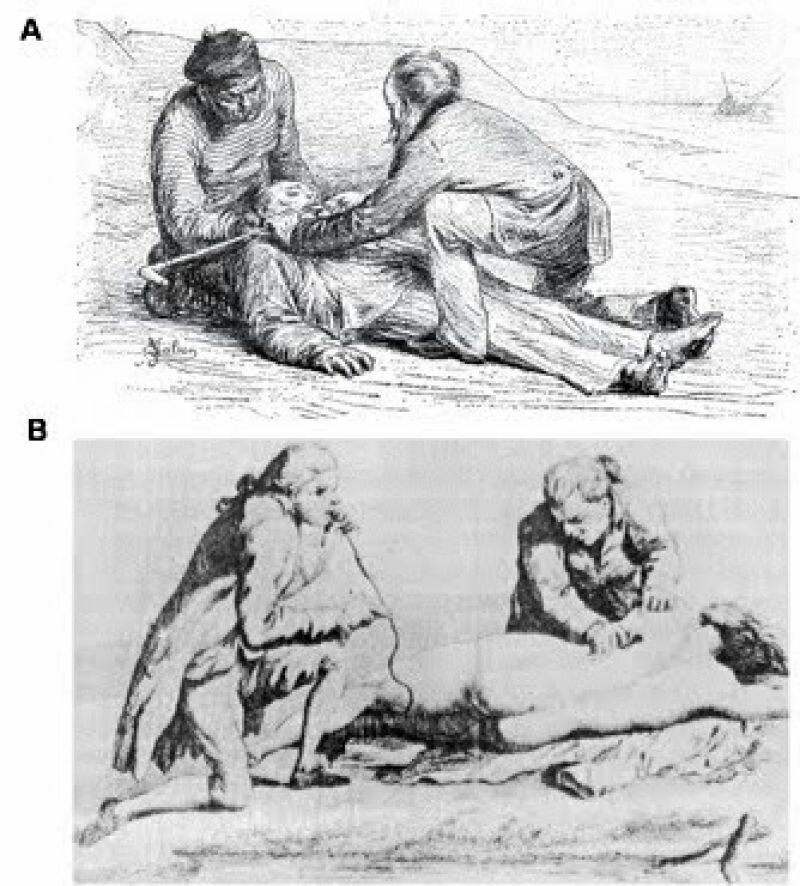

It was easy to revive the dead in the 18th century: just insert a tobacco resuscitator into the rectum and deliver a quick puff of smoke. The body would be stimulated back to life.

The kit comprised a bellows – originallya pig’s bladder – a tobacco pipe, a mouthpiece, and a cone for insertion. The technique gained popularity in 1746, when a drowned woman was resuscitated courtesy of a rolled piece of paper and a sailor’s pipe; a success story that saw ‘The Institution for Affording Immediate Relief to Persons Apparently Dead from Drowning’ install the kits at various points along the Thames, and build a centre by the Serpentine in Hyde Park to rescue drowned skaters.

Doubts about the credibility of tobacco-smoke enemas led to the phrase ‘blowing smoke up your arse’, no doubt after experiments, including a mass resuscitation effort in a Paris morgue, failed. Yet the object was standard medical practice across Europe and America for over a century, not just for resuscitation, but for treating constipation, strangulated hernias and intestinal obstructions.

A surviving example of the tobacco-smoke enema sits in a display case at London’s Wellcome Collection. This is the accompanying description: ‘There are no known accounts that the Tobacco Resuscitator worked.’ The label may be short but it has a subtext that says: ‘Look how foolish they were. We know better.’

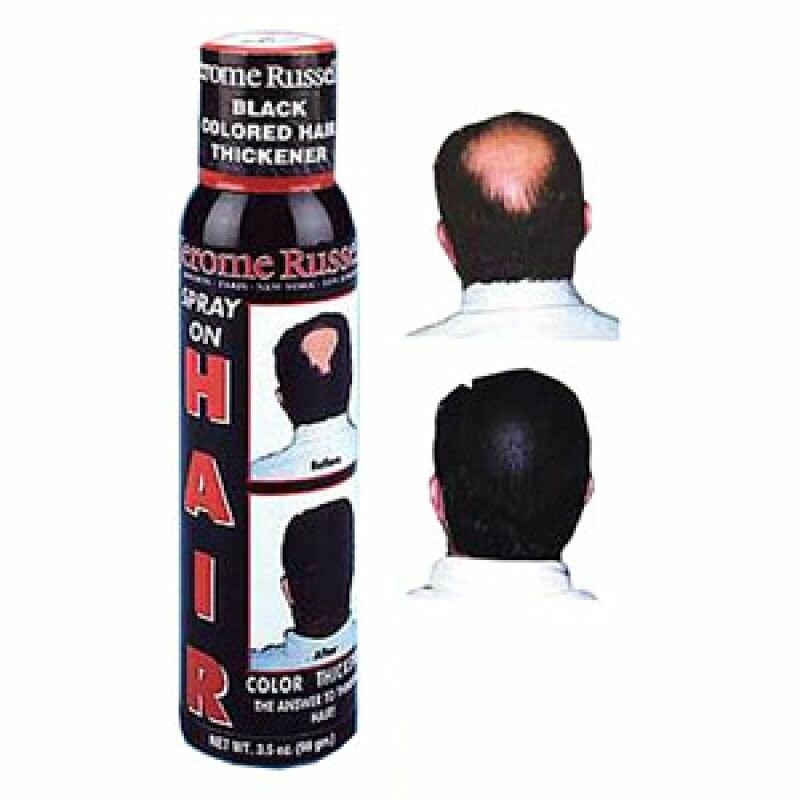

But do we? Just down the road from the museum, British model Kelly Brook’s derrière is the focus point of a billboard. She is wearing Reebok’s EasyTone trainers: a type of shoe that supposedly tones the buttocks 28 per cent more than regular shoes when you walk in them. The shoes are Reebok’s most successful new product in five years. Even when the Federal Trade Commission forced Reebok to rein in its claims, the shoes continued to sell.

This puzzle plays in my head later when I am flicking through TV channels and land on Pitch TV. Celebrity builder Tommy Walsh is demonstrating the Paint Pad Pro, a painting tool with ‘the speed of a roller and precision of a brush’. The paint glides over the patterned wallpaper, giving instant coverage: ‘It uses less paint than a brush, with minimum effort!’ I stare at my grubby walls.

Next channel: A woman delicately throws vinegar, oil, eggs, orange juice and a can of tomatoes onto a tiled floor. She picks up Whizz Mop, and moves it over the puddle. ‘Look at that! All gone and no streaks! And what do we do now?’ The male presenter smiles at the pretty assistant. ‘Whizz!’ she says, and places the Whizz Mop into a bucket, pumping a pedal to give the mop-head a spin dry.

Flick back: ‘And get the detachable extension pole too. No ladders – no splatters! And wait! We’re so confident that you’ll like this that we’ll double your pads for free!’ I go onto the Amazon website. Customers gave the product a blanket one star, except for a suspicious two who gave it five.

The tobacco resuscitator was administered in good faith; both the physician and the patient believed the product worked. But it is fairly obvious that the EasyTone shoes are not going to make you thinner, that the Whizz Mop and Paint Pad Pro are no faster, and no superior, to average mops and paint-rollers. So why, with the resources and knowledge available to us, do we continue to buy them?

Buckminster Fuller asked this question back in 1947 when he set up fictional company Obnoxico, to criticise those who make money selling worthless objects. The outlet was a faux mail order catalogue, and the star product was a gold cast of a baby’s last worn nappy; a memento of the moment a child is toilet trained, in object form. ‘Somehow or other the theoretical Obnoxico concept has now, twenty-five years later, become a burgeoning reality,’ Fuller reflected in the 1970s. ‘As the banking system pleads for more savings-account deposits (so that they can loan your money out to others at interest plus costs) the Obnoxico industry bleeds off an ever greater percentage of all the perennial savings as they are sentimentally or jokingly spent for acrylic toilet seats with dollar bills cast in the transparent plastic material.’

We live in a world filled with Obnoxico products, accompanied by a marketing industry highly skilled at mass manipulation. In 2004, two Czech film students created a supermarket, Czech Dream (Ceský Sen), in a Prague field. They employed a leading marketing agency to produce TV and radio ads, distribute 200,000 pamphlets and build a website, all boasting products at unbeatable prices. The project was filmed, and culminated in the opening of the building. The students, masquerading as businessmen, cut a ribbon, triggering 3,000 people, laden with shopping baskets, to run towards the hypermarket, only to reach a canvas façade supported by plinths. Their faces slowly turn to anguish as they realise they have been duped. The entire project was a fiction.

But marketing is not enough in itself to keep us buying Obnoxico products. Often, products with a dubious use-value have another, less obvious function that keeps them in the market. The useless tobacco resuscitator became useful for something else: to ritualise – in a rather unfortunate manner – the end of a life. The process gave a purpose to the doctor who arrived to pronounce a man dead, and set the grievers on their path, knowing that ‘we did everything we could’. For the survivors, the shock of the events quite possibly caused a psychological and bodily effect that aided recovery. Similarly, people who buy Reebok’s EasyTone shoes do so because they feel they are investing in their wellbeing, and this improves their state of mind. They may notice an improvement to their derrière even if there isn’t one.

This is called the placebo effect and has been defined by psychiatrists as ‘any therapy prescribed… for its therapeutic effect on a symptom or disease, but which is actually ineffective or not specifically effective for the symptom or disorder being treated’. In medicine, our belief in a pill’s ability to work sends a message to the pituitary gland to release its own endogenous pharmaceutics. The effect causes many red faces: when the pharmaceutical industry’s new wonder drugs are tested against sugar pills, half fail to beat the placebo. The same has been found for medical procedures. When physician Edzard Ernst performed an electrocardiogram diagnostic procedure on one of his elderly patients, the patient responded: ‘That was great. I feel much better, my chest pain has completely gone.’ Placebos are so effective, there’s a regular debate between government parties, doctors and psychologists as to whether they should be available on the NHS.

That unquestionable faith we once had in God, nature and even witchcraft to make us better is today transferred to science and technology. Functionless things, pills and procedures can improve our wellbeing simply through our belief in them. And they can easily be designed. That thermostat in your office probably has its wires cut, and is connected to nothing but your imagination. Turn the dial up and you’ll feel warmer; Wall Street bosses admitted that this act saved them a fortune. The ‘close door’ button in the elevator only works when the engineer plugs his key in; some say it exists to give us the illusion of control. Have you noticed how if you hit it repeatedly it seems to work?

So if the effects are good, is it right to deceive people, and wrong to tell people the truth? Perhaps sometimes, but because we don’t always know which things are placebos and which aren’t, we can’t critique them. They are an irreversible equation; they switch instantly from useful to useless once we know. We can’t decide at which point we need to know we are being duped – because then it’s too late. So should we allow people to orchestrate these elaborate spectacles in our mind?

Placebos – Latin for ‘I will please’ – work to various means; but as often as the intentions of duping us are good, they can as easily be driven by unsavoury goals. There is also the placebo’s evil twin to contend with: the nocebo, meaning ‘I will harm’. Voodoo curses that lead to death have been explained as extreme nocebo reactions. More recently, an autopsy of a man who died of terminal cancer revealed that his tumour was not large enough to cause death. Was it, the doctor suggested, the expectation of death that killed him?