I’m on my way to a house of retreat to sit through four days of silence. I’ve been anxious for weeks. My friend tells me I’ll be constantly preoccupied with sex because her friend staying at a similar retreat was overcome with all-encompassing feelings of lust that wouldn’t leave her alone. Similarly, there are two other silence seekers that I know of who fell prey to erotic fantasizing about fellow lodgers. One of these examples resulted in a wild a love making frenzy, the other triggered a stream of tears when the silence was broken with words that proved dishearteningly disappointing.

At this point, I’m expecting to find myself in a hermit-like state, without others, and without raging hormones to worry about. I’m mostly anxious about meeting the hostess. What if my stay is silent from the start, or we only every exchange an absolute minimum of words? I feel like an addict to words who’s being subjected to cold turkey withdrawal, after all, I’m an absolute novice when it comes to staying silent in the company of others. There’s no doubt that this experience won’t be the same as simply not speaking. I’m trying to put myself at ease. I’m normal, and normal people talk every day. For thirty years now, I’ve been speaking, although I naturally do my best to listen every now and then as well. It’s very reasonable that the prospect of complete silence instills fear in me.

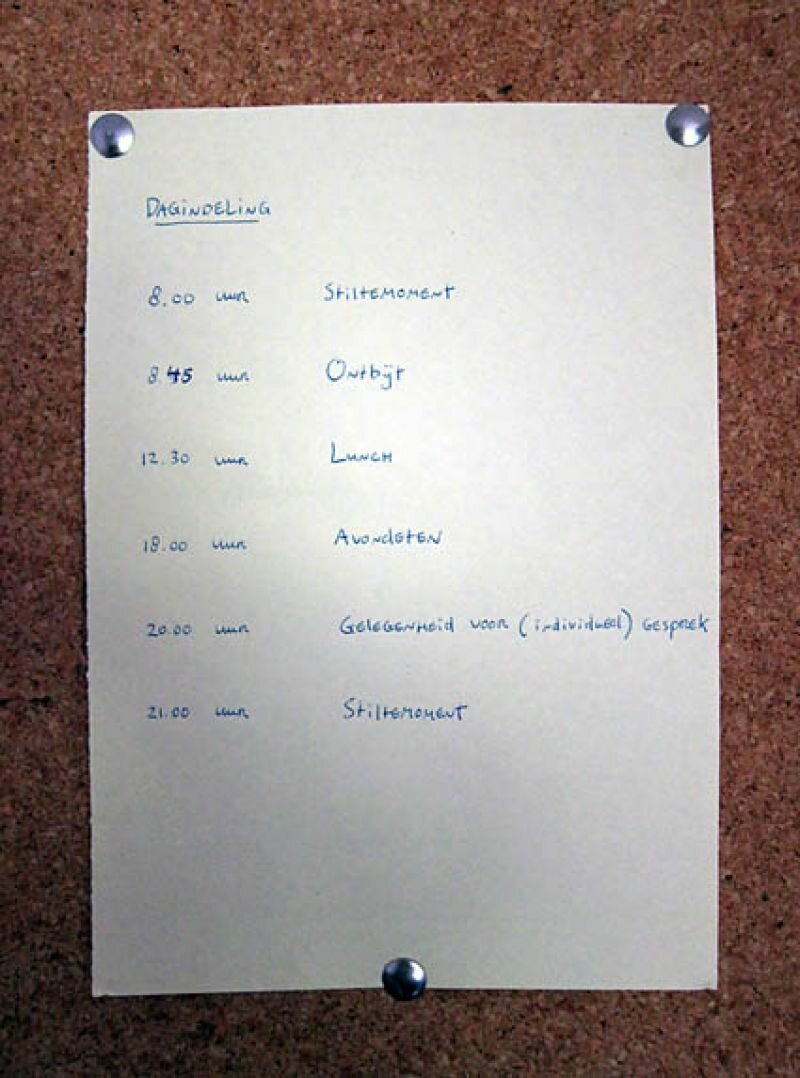

Everything seems strangely normal upon arrival. The doorbell rings, the hostess extends her hand, speaks her name. After a tour, the day’s rituals are described: besides the permanent solo-silence, there are three communal silent meals and two communal silent moments lasting a half hour each day. In the evening, one can converse if desired. I’m the only guest and am seated next to hostess A at a gigantic table suited for a dozen or so lodgers. The silence begins when we start our lunch. That is to say: verbal silence. With the lack of conversation, our bodies take the opportunity to make become loudly manifest. I can hear my jaws grinding and the muscles in my throat swallowing, alternated by the muted thundering of my intestines.

I thought I was an experienced eater, but it turns out that anything you focus your full attention on stops being straightforward. When has a mouthful of food been chewed sufficiently to swallow? How big should a bite be? A mouthful of fruit dwindles to nothing when chewed, while a bite of compact, home made bread expands to disturbing proportions. Could it be that one of the prime functions of conversation is to distract us from the noises our bodies make? I’m extremely aware of A to my left, and am constantly attuned to her rhythm. We finish our sandwiches at almost the exact same moment. My chewing is slower, but it takes her longer to pick what she wants on her sandwich. I watch her movements from the corner of my eye. This crooked gaze is difficult to sustain, and so my pupils escape every now and then to take a flight of exploration.

My eyes might, for example, travel over her plate and see how far she is in eating her meal. If I glide my gaze, making sure it doesn’t hang over any one thing for too long, I brave looking halfway between her elbows and her armpits. Beyond the plate lies a border: that’s where the forbidden terrain of her upper body begins, and above that the face where the food enters and disappears.

It’s only when I offer A tea in three words that I dare to make eye contact with her. Could it be that you’re only meant to make eye contact with one another during an exchange of words? Could it be that the reason we speak to each other is mainly to be allowed to look at one another?

Column on a stay at a house of retreat, published online in art magazine LUCY from CBK Utrecht on 30th of Augustus 2011.